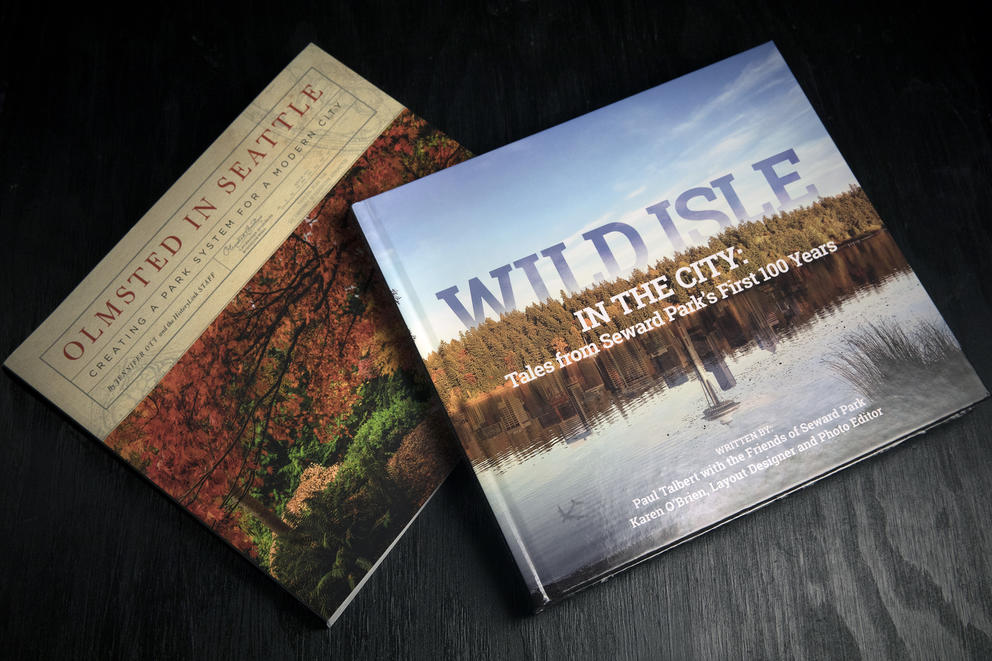

One is Wild Isle in the City: Tales from Seward Park’s First 100 Years by Paul Talbert. The author is a co-founder of the Friends of Seward Park, a community group that works diligently to steward and improve the park, from removing invasive ivy and restoring a Garry oak prairie once tended by the Duwamish lake people to raising a new Japanese torii, or gate.

Talbert is a passionate advocate, but also a diligent student of the park’s human and natural history. He writes about the big-picture geology that shaped the park, as well as details about the microscopic critters that live there. Working in collaboration with the Friends of Seward Park, which published the book, he spent some eight years creating the definitive and lavishly illustrated history of Seattle most remarkable park.

Seward Park sticks into Lake Washington at the south end of Lake Washington Boulevard, a thumblike projection of land once commonly referred to as Bailey Peninsula after its absentee family owners. In earlier times, when the lake’s water level rose and fell naturally, it was sometimes an island and as such was detached just enough that, between the inconvenience of an island and having nonresident owners, no one logged its old growth. Some 120 acres of that survives in the roughly 300-acre park.

In booming Seattle of the late 19th century, however, a few Seattleites recognized that such forest was rapidly becoming an isolated and precious commodity, especially in a city built largely by the timber industry. In 1892, Edward Schwagerl, the parks superintendent, first suggested the Bailey forest be protected.

“Parks are full of Nature’s innocent and holy inspirations,” he wrote, “and in them are the whispers of peace and joy. Parks are the breathing lungs and beating hearts of great cities.” That is even truer today, as we realize the value of tree canopy and the need for healthful space amid increasing density.

This was not the attitude of pioneers like Seattle’s founding sawmill owner Henry Yesler, or folks like the timber baron Weyerhaeusers. The financial panic of 1893 shelved Schwagerl’s noble aspirations and, perhaps fortunately, slowed development for a time. But the significance of his proposal was that it signaled a shift in Seattle’s attitude toward nature: It should be an integral and internal part of building a great city, not simply the supplier of timber for construction or something to be viewed from afar. A city with nature in abundance could be greater than most cities if it managed nature well.

This, of course, is a continual push-pull battle with growth. We are lucky that the need for parks was recognized so early that land could be saved and nurtured for the long term. We, indeed, still had what many eastern cities had lost.

Seattle made its next foray into parks in the wake of the early 20th century economic boom driven by the Klondike Gold Rush. Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of New York City’s Central Park and many others, set a new standard for urban parks: accessible to all. His stepson and nephew, John Charles Olmsted, took over the family landscaping business and was brought to Seattle in 1903 to plan a park and boulevard system. This is the subject of a second new book, by landscape historian Jennifer Ott and the staff of Historylink, Olmsted in Seattle: Creating a Park System for a Modern City.

For decades to come, Olmsted worked with Seattle’s engineers and architects to create a structure for nature and parks to shape and serve the rapidly growing city. This included the landscaping plan for the 1909 Alaska Yukon Exposition. In addition, the team converted an extensive system of bike paths (like Interlaken) for cars, preserved pockets of forest (Schmitz Park in West Seattle), developed and refined major parks like Volunteer Park on Capitol Hill and proposed and largely built a series of streets connecting them all across every corner of the city.

It was a triumph of landscape over grid. A century later, you can ride or drive from one end of town to another following curvy shoreline, stream beds, surviving green belts and ridgelines.

On his very first trip to Seattle, John Olmsted visited the Bailey Peninsula. He saw its virtues and argued that it be “secured … before the woods are injured.” Though not yet within the city limits, the acreage was identified as a must-have, and the city soon annexed the land around it. In 1910, the city purchased the property.

Olmsted’s vision for the park was not executed, however. He imagined building more auto loops through it and connecting it to the mainland with a small bridge — the latter rendered unnecessary when Lake Washington was lowered some 9 feet in 1916 by the opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal. With that development, the future Seward Park, a sometime isle, became a permanent part of the mainland.

In reading about city parks, and how they have evolved, one realizes how complicated they are, and while our parks have endured, they need constant tending and adapting. Seward contains the most dramatic specimens of old-growth forest in the city, including Douglas fir estimated to be 500 years old. That one can experience such trees in the middle of a modern city within the sounds of the Sea-Tac Airport flight path is nothing short of remarkable.

But Seward is more than a forest preserve. It has been reshaped and developed over the years. It wasn’t clear cut, but parts of have been logged — the city was cutting firewood there into the mid-20th century. It was home to a fish hatchery (now closed), a lake (that has somehow disappeared), an amphitheater along with extensive grounds and shelters for picnics.

Some of the land was cleared by walloping wind storms in the 1920s and ’30s. Its swimming beach is popular. A charming old concession stand in the form of a cottage has been transformed into an Audubon Center for nature lovers, with a white board where visitors mark their latest sightings: eagles (at least two pairs nest there), otters, muskrats, pileated woodpeckers, owls, etc. An arts studio is housed in an old bathhouse.

One of the major loop roads that follows the peninsula’s perimeter used to be a kind of gathering place for teens and cars — a kind of Alki for South Seattle teens in the ’50s and ’60s, until it was closed to foot traffic and bikes in the early 1970s. One rationale was to keep riff-raff from the park, but it’s hard to argue with the wisdom of it, given our future as a city that wants to minimize cars. Some of that shoreline is also part of an effort to restore habitat for native salmon.

Urban parks change with their cities and neighborhoods. At Seward, this is particularly evident in the park’s visitors. It is adjacent to some of Seattle’s most diverse neighborhoods, but has a long history as a site for commemorated friendship with Japan. For example an eight-ton granite lantern sits in a park garden given to Seattle in 1930 in commemoration of the city's aid to Japan after a damaging 1923 earthquake.

There have been Filipino community festivals and jazz and rock concerts back in the day (I once saw Little Richard perform there). It is a place where you can find people from the nearby Jewish communities walking the park along with East African women in head scarves. Wilde Isle contains accounts of diverse Seward Park user experiences that underscore the wide community impacted by it. (Full disclosure: a photograph of my father and me in Seward Park circa 1955 graces page 305 of the book. Proof that I am a lifelong Seward Park user.)

Race and class have played large roles in the shaping of parks. John Muir — namesake of the South Seattle school I attended in Mount Baker — urged the preservation of nature to ease the lives of the growing urban middle class and inspired men like Frederick Law Olmsted, but he also expressed contempt for the Indigenous people displaced from his beloved Yosemite lands.

Some of the greatest proponents of protecting nature had overtly white supremacist views. Park and environmental priorities in the past have often put white, affluent neighborhoods’ desires above others. Redlined neighborhoods and housing covenants meant people of color had limited access to parks.

In that light, it is all the more remarkable that parks like Seward have not only been able to protect the experience of “Nature’s innocent … inspirations,” but also overcome some of the not-so-innocent ideas driving their creation. They now serve much more diverse urban communities than they might have in the beginning. That will continue to be a challenge, as we look to create and evolve our parks in the future and seek to recover some economic balance between classes.

Another challenge is stewardship of nature under stress from a changing environment. Climate change, for one. Loss of habitat for another. Mystery challenges, too. Seward, for example, has been hit with a major die-off of ferns, possibly from a pathogen of some kind. Friends of Seward Park hired scientists to help find answers.

The parks are not wild — they require tending. Their usefulness shifts with the population and its demands. But make no mistake: The parks and boulevards of Seattle form a brilliant anatomy around which the urban body has grown and intertwined. These books are a reminder of how rich and special that legacy is, and how it can never be taken for granted.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.