She can show you how a sandwich of grilled manchego cheese and sausage on peasant bread is made in the style of a master chef from Catalonia. For dessert, she’ll tempt you with a wicked coconut-caramel cake with malted chocolate frosting.

But when the leftovers are wrapped and put away, Wright can also impart some hard-won wisdom: how to talk to kids about death.

Wright, who studied cuisine at a renowned cooking school in Burgundy, France, always wanted to write as much as develop her skills in a well-appointed kitchen. At age 23, she became a food editor at Martha Stewart Living, and later brought her crisp, engaging voice to her cookbooks, Twenty-Dollar, Twenty-Minute Meals, Cake Magic! and Catalan Food: Culture and Flavors from the Mediterranean (co-authored with Daniel Olivella).

She hasn’t stopped writing about food. But in 2017 she was diagnosed with a glioblastoma, an aggressive, rapidly growing brain tumor, similar to the one that killed Sen. John McCain. With the possibility of death looming large, Wright turned her prose toward facing her own mortality — and starting the conversation with her kids.

Luminous and voluble in person, Wright is a self-described, inveterate doer. When not writing or cooking, she’s pursuing photography or quilting or knitting. She can’t stop making things happen, whether it’s tinkering with recipes for her next cookbook, or organizing a panel discussion at Town Hall (Saturday, Nov. 9) on children and grief. The event will explore how we talk to kids about death, a topic with no simple bearings.

Wright has written two recent books on the theme of child bereavement, inspired by her and her husband Garth’s agonizing challenge of communicating with their young sons about Wright’s still-uncertain prognosis.

The Caring Bridge Project (which came out in February) is a collection of Wright’s online journal entries from her year of chemotherapy and radiation treatment. It’s part of Wright’s written legacy to her boys, Henry, 7, and Theodore, 4. But she intended it, too, for a broader readership: families facing similar experiences with children’s anxiety and despair over loss.

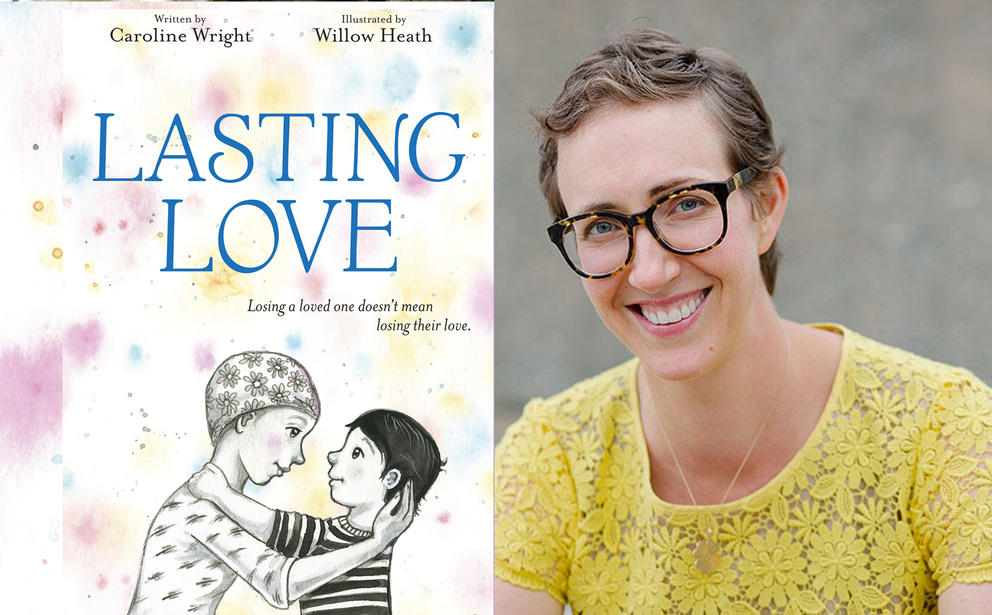

This past summer she published Lasting Love, a picture book for reading aloud to bereaved kids. The heartbreaking but emotionally affirming story, with comforting illustrations by Willow Heath, is about a dying mother returning home from the hospital with a formidable friend: a mighty, furry creature who will always remain by her child’s side, as both an avatar of her powerful love, and as a faithful companion who never judges grief in any form.

Halfway through the tale, the mother passes.

“The child would know,” says Wright of her decision to include the mother’s death. “So stepping around that seemed silly. I wanted the kid to be part of spreading her ashes.”

For Wright, there was no option but honesty. She knew her kids would watch her change, physically, during treatment, and they would find her less available. Keeping them in the dark — especially the older boy, Henry — would have been unfair. “The thing kids can’t rebound from is broken trust,” she says. “There’s no resolution for that.”

When she and Garth first talked with Henry about her cancer, and how she and her doctors were doing everything they could, but she might die anyway, there were tears. But Henry devised a helpful analogy:

“Mommy’s brain is a garden, and there’s a weed in it.”

“Henry and I have had amazing conversations, poetic and hard,” Wright says. “If I die, I want both boys to have a relationship with their memories of me. If I lied to them, it would sully that relationship.”

Thirty-two months after Wright was told she’d likely have 12 to 18 months to live, she is miraculously cancer-free, but vulnerable to a swift reemergence of the glioblastoma. If you take cancer out of the picture, she actually became healthier while fighting the disease, radically changing her diet, dropping 40 pounds and growing lean and strong through yoga, energy work and exercise.

Wright says the boys now occasionally bring up her cancer at random times. When Theodore recently saw her short hair wet and matted after a shower, he grew weepy, recalling her treatment-related baldness, and associating it with being away from him.

The profundity of loss, and the despondency of a child left without the constancy of a loved one’s care, makes Lasting Love a benevolent bridge between a parent and son or daughter going through these troubles.

“The theme of Lasting Love is, literally, love lasting forever,” Wright says. “That’s what we were telling Henry. That was the only piece of hope that we could give him: Mommy’s fighting very hard. And even if mommy dies, the connection you have with her is never going to go away. And there are many loving people surrounding you.”

Wright’s Town Hall event is part of her outreach mission to regional families and to nonprofits concerned with children and bereavement. Among them is Safe Crossings, which supports grieving kids of all ages, at little or no cost. Amy Thompson, program coordinator, will join the panel, along with therapists from other organizations.

Thompson says the field of grief counseling for early childhood through adolescence is growing because of a rise in traumatic losses: gun-related murders, opioid-overdose deaths and suicides. Grieving kids are often isolated, subject to bullying, and told to “get over it” by clueless adults.

“The message from society to grieving young people is ‘move on,’ ” Thompson says. “But if you’re intensely grieving for months or even years after a death, there’s nothing wrong with you. Loss changes over time. As children grow and reach new developmental milestones, they can better process the permanency of death, and we see them regrieve.”

The attention Wright and Lasting Love are receiving in therapy circles and in the media is helping to normalize grief in children — in everyone, really. When she learned she had beaten seemingly impossible odds and, while not out of the woods, is without cancer, Wright celebrated with her family by making a favorite cake, although with a few adjustments: it was sugar-free, gluten-free and covered in carob frosting instead of her once-beloved chocolate.

“I live with great respect for this thing that may happen to me again,” Wright says of the glioblastoma cells that might still be lurking in her brain. “But I don’t live in fear of it. There is nothing to be gained by that. I might die and I might not.”

But the bond between parent and child will last beyond death, she says. “Kids are resilient. With support, they will have full lives.”