The route was first mapped circa 990 A.D. by power walker Sigeric the Serious, Archbishop of Canterbury. Sigeric covered an average of 12 miles a day on the path from Canterbury to Rome and back again (1,110-miles each way). The purpose of his visit to the Eternal City? Picking up a vestment from the pope.

Egan’s planned journey, also by foot, was less about transporting the trappings of Catholicism, and more about coming to terms with tattered religious convictions.

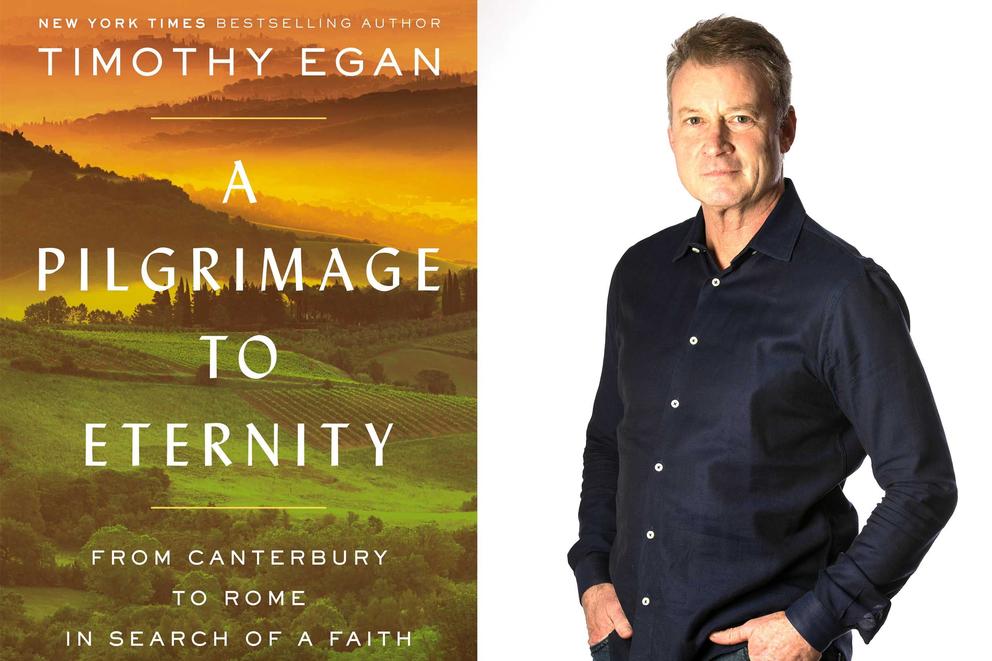

In his remarkable, moving ninth book, A Pilgrimage to Eternity: From Canterbury to Rome in Search of a Faith, Egan — who won the National Book Award in 2006 for his nonfiction book The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl — describes his blister-inducing odyssey on the historic Via Francigena trail. Over a number of weeks, Egan walked from the United Kingdom to France, and across Switzerland into Italy.

Throughout centuries, tens of thousands of Christians have endured hardships, danger and brutal elements on this same taxing adventure in order to sharpen their religious beliefs and affinity with the Church of Rome.

As with those predecessors' treks, Egan’s pilgrimage was both physical and metaphorical, rendering him vulnerable in body and soul. The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist entered into his challenge without his customary armor of objective detachment, transparently seeking answers to tough, complicated questions about the state of his spiritual life. As a historian (see 2016’s The Immortal Irishman: The Irish Revolutionary Who Became an American Hero), chronicler and weekly columnist with the New York Times, Egan might occasionally write in a first-person voice. But he rarely puts himself at the center of a story.

Things were different with Pilgrimage.

“It’s one of the hardest things I’ve ever done,” says Egan. “I had a couple of friends who encouraged me to be even more personal, and it was just very difficult. You spend your whole professional life writing in a third-person remove. It’s very difficult to open a vein, and I struggled with how much to expose myself. I think it’s the only way you can be honest with a reader in a book like this.”

His impetus for embarking on the Via Francigena was twofold, with one development close to home and the other global.

“The first was my mother’s death, which moved me to be sincere in looking at the issues that guided her life. And then Pope Francis opened all these windows. He dismissed [anti-gay bias] in the church with one line: ‘Who am I to judge?’ That’s been tying up Catholics for centuries. Who cares about doctrine? Francis washes the feet of the poor. Gives comfort to people with AIDS, says nations have an obligation to let refugees in. Here’s a guy trying to live by the actual words of the Gospels.”

Amid one of the blazing hot summers that Western Europe now suffers in our climate-challenged world, Egan covers miles and miles of the Via Francigena, short of water, his sweat-drenched clothes plastered to his exhausted and injured body, at times sharing rural roads with cars whose passengers mock pilgrims.

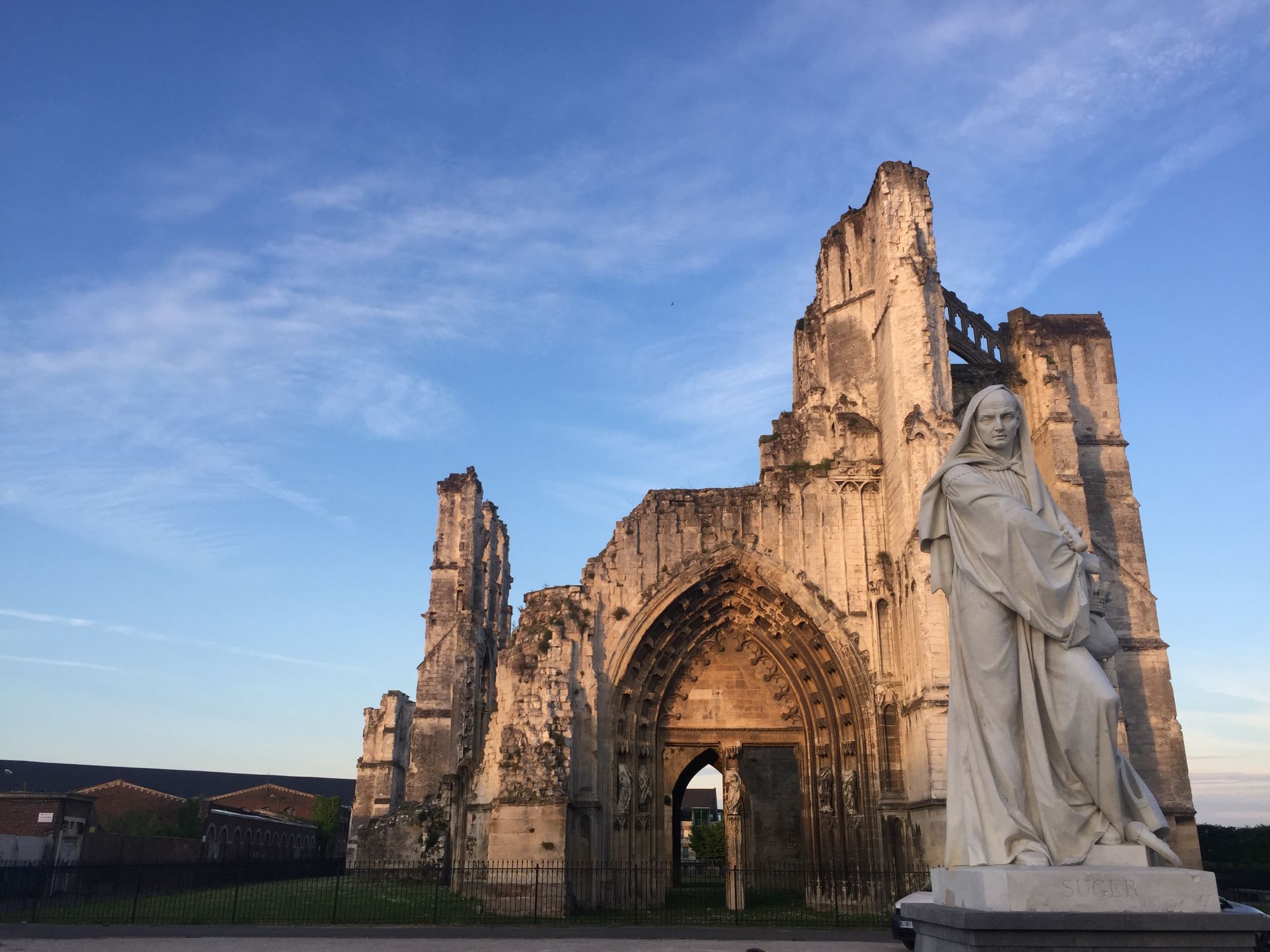

He stops in cities and villages, cramming in visits to majestic cathedrals and small, ancient churches alike; to sites of holy relics (i.e., random bones of exalted saints); and to the murder scenes of martyrs, including Thomas Becket and Joan of Arc. He takes sparse food and bare lodgings at monasteries. In one of the book’s most gripping sections, he dons his REI best to make his way through a deadly, stormy stretch of the Alps:

“My feet feel clammy; the rain has found a way inside because I’m not wearing gaiters.... When I planned this trip, I envisioned the top tier of the Via Francigena as a heavenly walk through alpine meadows, a wildflower show at the peak of its ostentation, marmots whistling in chorus, with maybe a glimpse of Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps, showing some part of its albino essence.... I didn’t envision a struggle in a place that has the colorless feel of an anxious dream.”

Throughout, Egan reflects on the church’s denigration of women; on how a tiny cult of early followers of Jesus became the war machine of empires; about stage 4 cancer in a loved one back home; and how the mistreatment of children by pedophile priests (and their enablers in church hierarchy) tragically crossed paths with Egan’s large, Spokane-based family of blue-collar Irish Catholics.

“I wanted the book to be three things: a history of Christianity, a great armchair travel adventure and a personal story,” he says. “The experience forced me to face issues I haven’t thought about for a long, long time.”

Prior to his travels, Egan was living in a gray area of lapsed-Catholic uncertainty about his core beliefs, such as the authenticity and meaningfulness of Jesus’s resurrection in the New Testament. Figuring out — in his early 60s — if he accepts, rejects or equivocates on Christianity’s foundational story is a major goal of his step-by-step progress.

“I tried to say, right up front: I’m not a theologian. I don’t care about fights over whether a divorced Catholic can take Holy Communion. I just wanted to shake away my cynicism, my skepticism, and just be open for once to this 2,000-year-old, compressed story of spirituality, and see what I can find.”

It would be a mistake to assume Pilgrimage is strictly for Christian readers. Fans of Egan’s writing and newcomers will both enjoy his deep immersion into descriptive language that jolts the past awake with sensory immediacy. In a stunning scene that greets Egan in Calais, a ferry port in northern France, Syrian refugees are boxed in by French security forces and hostility.

“I pass a pair of bomb-sniffing dogs leashed to a pair of assault-rifle-toting gendarmes,” Egan writes. “The police wear bulletproof vests and talk grimly into their shoulders. Here comes another pair, and another, and a fourth. This is occupied Calais.

“My fellow pilgrims are trying to find religion,” he continues. “The authorities pay no attention to us. Silly walkers with their floppy hats and overpocketed cargo pants.... But thousands of others are trying to flee religion. The police are all over them.... They were asylum seekers, these foreigners, a fifth of them children without adults.”

Back at home, Egan says, “I like to give readers a sense of what the textural feel of history is like. I don’t like to go into the archives and summarize what other people are saying. I like to give readers a touch, a tactile sense. And a journey is the best way. If a reader doesn’t care about the pilgrimage, he can enjoy the ride.”

When all is said and done, the book is really about the hard work of answering what we can about the big questions: How we got here. What we’re each meant to do. Where we go next. Perhaps, more importantly, how we accept the wisdom that no matter our hunger to know it all, we simply can’t.

“I hoped to tie up a lot of the issues I started with,” says Egan. “But I really couldn’t with some things. I realized the not knowing is OK. I think every human being, at some point in life, has to try to answer these questions. No matter how secular a society you live in, or what kind of faith you have, we are all spiritual human beings. Yet we suffer from malnutrition of the soul. We don’t feed our appetite for that. But I feel like I finally did. I’m sated.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.