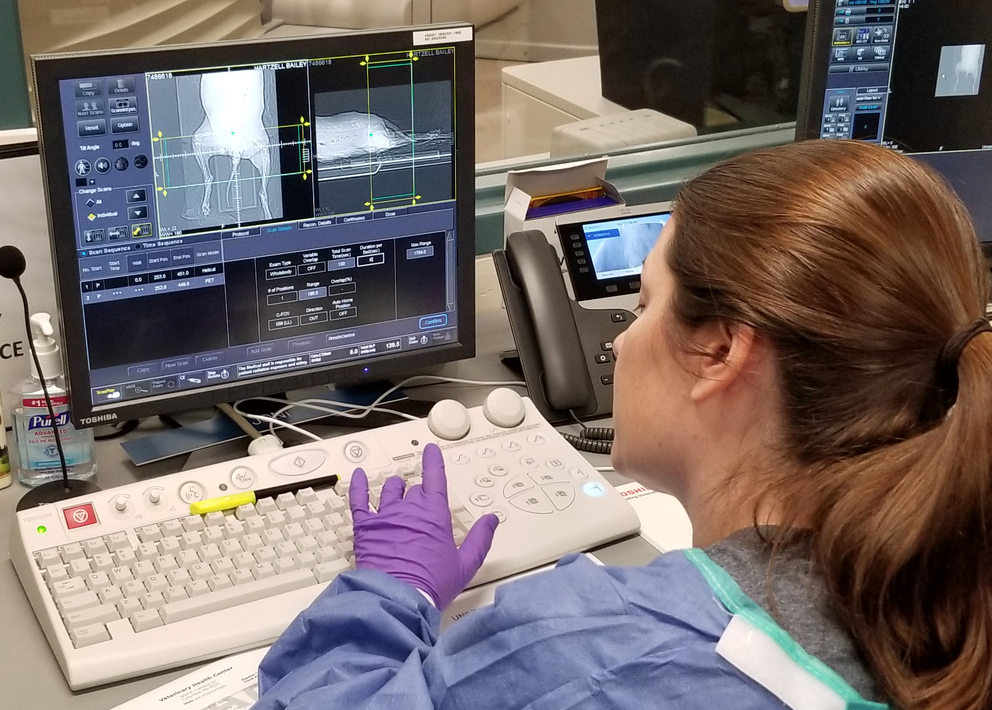

Less than 10 minutes later, Dr. Darrell Fisher, a medical physicist based in Richland, Benton County, who helped invent IsoPet, looked at the scan’s results on the computer screen. What looked like a white blob on the scan was exactly the result they’d hoped for: The radiation gel they’d injected into the dog spread evenly throughout the entire tumor without spreading to surrounding healthy tissue.

“This was it, this was the solid evidence that we were able to achieve uniform distribution,” Fisher says. “I’ll never forget that.”

The test results meant more than a longer life for the dog. It represented a potential breakthrough in treating cancer with radiation for Vivos, the Richland-based pharmaceutical company that developed and produced the treatment in conjunction with Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Pets are just the first step. Eventually, the team wants it to be available to treat cancer in humans. If approved by the Food and Drug Administration, the product will be called RadioGel, as the FDA requires a different name for human use.

Vivos’ next step is to collect enough safety and efficacy data to get premarket approval from the FDA. Vivos CEO Dr. Mike Korenko says that process will take about a year and cost about $1.5 million; once completed, Vivos can move on to clinical trials in humans.

Right now, the treatment is available to the public only at Vista Veterinary Hospital in Kennewick. Vivos hopes to make it available to veterinarians across the country within six months, says Korenko.

Korenko is also reaching out to human hospitals. He spoke with a representative from the Mayo Clinic at a medical conference and has reached out to St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital. It may be especially helpful for kids, Korenko says, since chemotherapy is especially damaging to growing tissue. He says the doctors he spoke to were eager to learn more about potential use in humans.

“[On] the human side, you talk to a doctor, and they said, ‘My God, [this] is the first [new] tool in our toolbox we've had in 20 to 25 years,’” Korenko says. “So it's pretty exciting, [but] it's going to take us four or five years to get into human therapy.”

Treatment for pets currently costs about $9,500. Korenko wants to lower the price as soon as possible, saying he doesn’t want to treat only “rich people’s cats and dogs.” The first animal to receive IsoPet treatment outside of clinical trials at veterinary schools was Drake, a black and gray cat with a facial tumor. He was flown in from Sitka, Alaska, by his owner, veterinarian Dr. Burgess Bauder. Drake was treated at Vista Veterinary Hospital by Dr. Michelle Meyer, the first vet to be certified to administer the gel outside of trials.

On July 10, Drake was given a physical examination and anesthetized, and the area around his facial tumor was shaved and prepped. A grid was drawn with marker to make sure injections were 5 millimeters apart.

To prepare IsoPet, two vials, both on ice, were combined: one with radioactive particles in a liquid and the other with a liquid that gels when warmed by body temperature. Meyer gave Drake multiple injections over a period of 20 minutes. A technician trained in the handling and transport of the radiation stood by alongside a radiation safety officer.

“It was pretty amazing, just to be a part of it and to see the pictures afterwards of Drake and see how well it’s working,” Meyer says.

Almost two months after the injections, Bauder says the tumor has decreased by about 90%.

There are limitations to IsoPet/RadioGel’s practical uses. Cancers with solid, isolated tumors represent the best treatment cases; it’s not appropriate for widely disseminated cancers, like leukemia or metastatic breast cancer.

“If the cancer is spread through lungs and liver and spinal cord and brain, this is not for that,” Fisher says. “But if one needs to treat single, solid tumors, this is just the ticket. It’s the cat’s meow.”