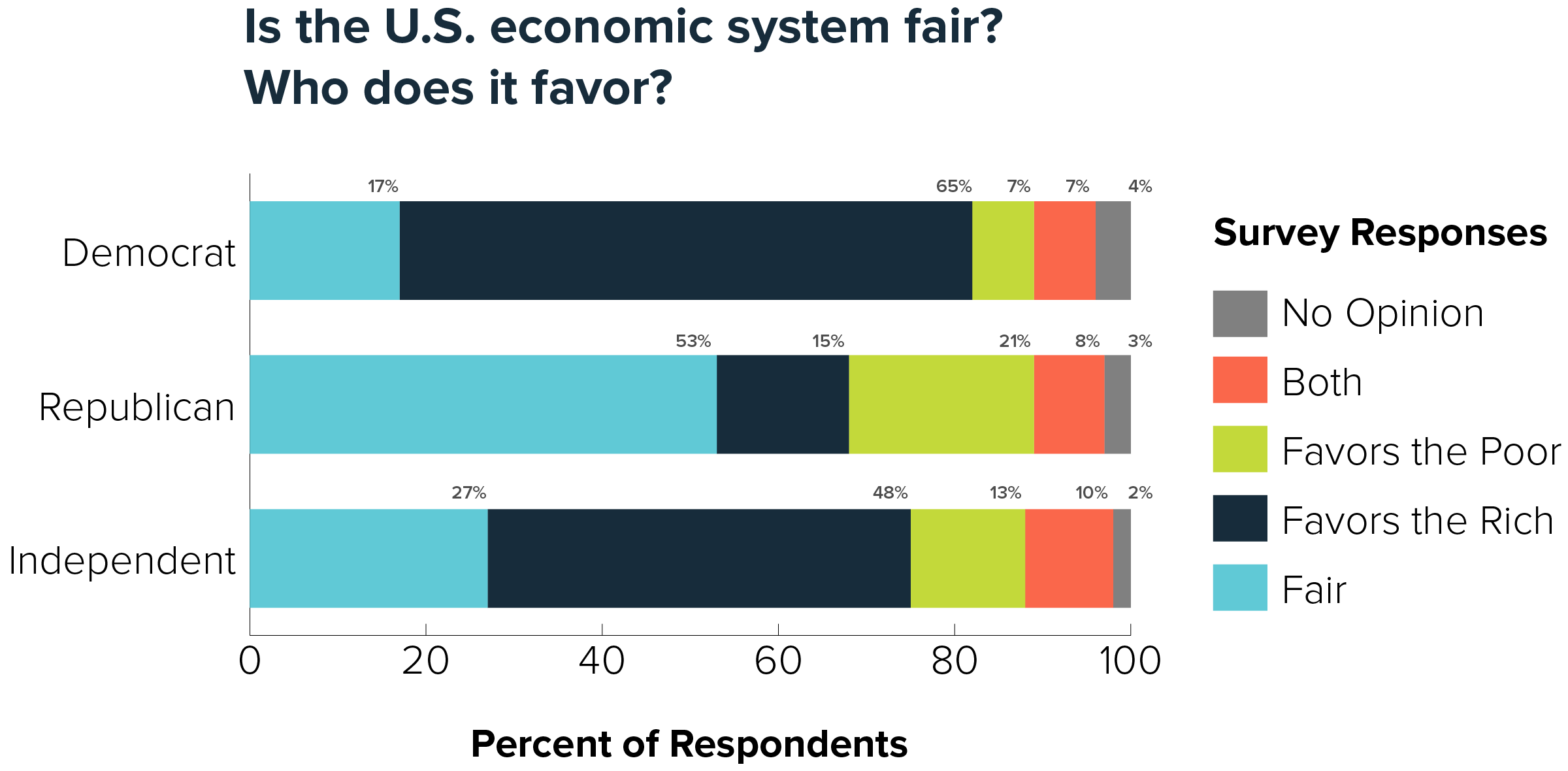

The subset with the highest percentage suggesting the system is rigged for the wealthy is Seattle: 70%. The second highest, 57%, is in Pierce and Kitsap counties, areas that tend to skew a little more conservative than others in the central Puget Sound area. Overall, Democrats (65%) and independents (48%) are the most skeptical; Republicans the least (16%). The sense of unfairness increased with a respondent’s education level.

Despite deep divisions in our politics, blaming the rich for our woes shows that populist sentiment is alive and well. It has happened before in our history. Populism has reared its head near the peak of economic boom times when economic inequities have been exacerbated. A possible coming recession also can trigger fears among Blues, Purples and Reds about who is going to lose in future economies.

“I think the widespread perception that the system is unfair explains a lot about the appeal of both Donald Trump, and Bernie Sanders/Elizabeth Warren,” says Stuart Elway, who conducted the poll.

“We do have a populist president,” adds Marco Lowe, political science professor at Seattle University.

Populism does not appear to be going away any time soon. The 2020 presidential election could very well come down to a choice between two types of populism, left and right. Trump touts the consumer economy and takes tough stances on trade with China, while emphasizing jobs for unemployed rust belt workers and stirring fear and hatred of immigrants. From tariffs and nationalism to bashing the Federal Reserve, he’s using the classic paranoid populist playbook.

Of the top three Democratic challengers, Sens. Sanders and Warren, virtually tied for second place with former Vice President and political centrist and establishmentarian Joe Biden, are using broad populist appeals — free college tuition, cracking down on ever-more powerful tech companies, forgiving student loan debt, Medicare for all. They routinely attack Wall Street, big banks and big corporations.

The perception of economic unfairness “filtered through a partisan lens leads to populist impulses in the demographic bases of both parties,” Elway observes.

Washington state has its own history of populist politics. A notable example has been detailed by historian Gordon B. Ridgeway, who points to a time shortly after statehood in 1889, when populist discontent rose after a booming frontier growth period that featured unprecedented prosperity.

Despite the boom, Washington farmers felt marginalized and exploited by railroad monopolies that charged outrageous freight fees to get their produce to markets. They organized Granges and Farmer Alliances to push back. Labor was discontent with working conditions and exploitation, and rising costs. Economic reformers wanted a monetary system based on silver rather than gold to help the common man. Parties began to re-align, and new ones emerged.

Fears over immigration were also on the rise. The “frontier” was declared “closed” in 1890, limiting homesteading opportunities and driving up the price of land. A populist party was formed here in 1892 and by 1896 Washington voters had elected our first and only populist governor, flipped both houses of the Legislature to the populist fusion party, relegated the Democrats to a distant minority party, and elected a full slate of populist state officials. The new governor, John R. Rogers, a prairie populist from Puyallup, argued for new taxes on the wealthy to spare the little guy.

Nothing like that seems to be in the offing, but it’s fascinating that the most economically successful parts of the state, Seattle and Puget Sound, are most suspicious of wealth and power. Lowe thinks part of it is likely driven by things like housing costs and rapid growth, which have made much of the region barely affordable to average wage earners. Find someone—and it isn’t hard—trying to pay rent in Seattle and who is facing potential displacement and you might well meet a budding populist, or socialist.

Another issue likely impacting local attitudes toward the wealthy: a sense that the massive GOP tax cuts didn’t live up to their billing, that the benefits going to the wealthiest people and corporations are not trickling down. According to the Elway poll, 20% of respondents in Washington legislative districts that went for Trump in 2016 report that the tax cuts had a negative impact on their household, and 49% said they have had no impact. That’s nearly 70% of those polled in Trump-sympathetic districts saying “ugh” or “meh” to Trump’s signature tax-cutting achievement. Less than a third, 27%, thought it had a positive effect. The results in districts that voted for Hillary Clinton are similarly lackluster: 24% positive, 24% negative and 45% none. In other words, most Washington households do not feel they benefited from the tax cuts. Surely this could be reflected in attitudes toward the rich and powerful.

Trump is not popular in Washington and has tarnished the GOP brand here. Still, a feature of populist campaigns, says Lowe, is a candidate who rises above party and incites emotion in unlikely voters. Arlie Russell Hochschild, a UC Berkeley sociologist who has studied the anxieties of rural white voters in northern Louisiana, has described how during a 2016 Trump event, candidate Trump descended in a helicopter and some supporters held signs suggesting that he was the “second coming,” a point highlighted this week when Trump retweeted a reference to himself as the “second coming” of God for Israelis. For some, the president represents a kind of populist political Parousia that has moved some of his followers. He still has emotional appeal for many, though whether that means anything here is questionable.

On the left, in 2016, I remember seeing more Bernie Sanders signs in rural Washington than Clinton ones. Whether Sanders will catch fire this time is unknown. Lowe points to a recent moment from an Elizabeth Warren campaign stop in West Virginia, where she has highlighted the damage done to rural communities by the opioid epidemic. According to Politico, “She went full prairie populist, telling people their pain and suffering was caused by predatory pharmaceutical barons.” Warren also reads notes voters pass to her at campaign events—many people seem to feel an emotional connection at her rallies, perhaps partly because of her Oklahoma roots. Populist appeal is “infectious,” Lowe says. “You cannot capture that in a jar.”

Nor can a poll tell us how Washington state’s frustrations with the rich and powerful will or won’t manifest. With Gov. Jay Inslee running for re-election (a third term) after ending his presidential bid, it could be a pretty status quo election in the state. Still, it will be interesting to see what the populist “jar” might hold in races here and around the country in 2020.