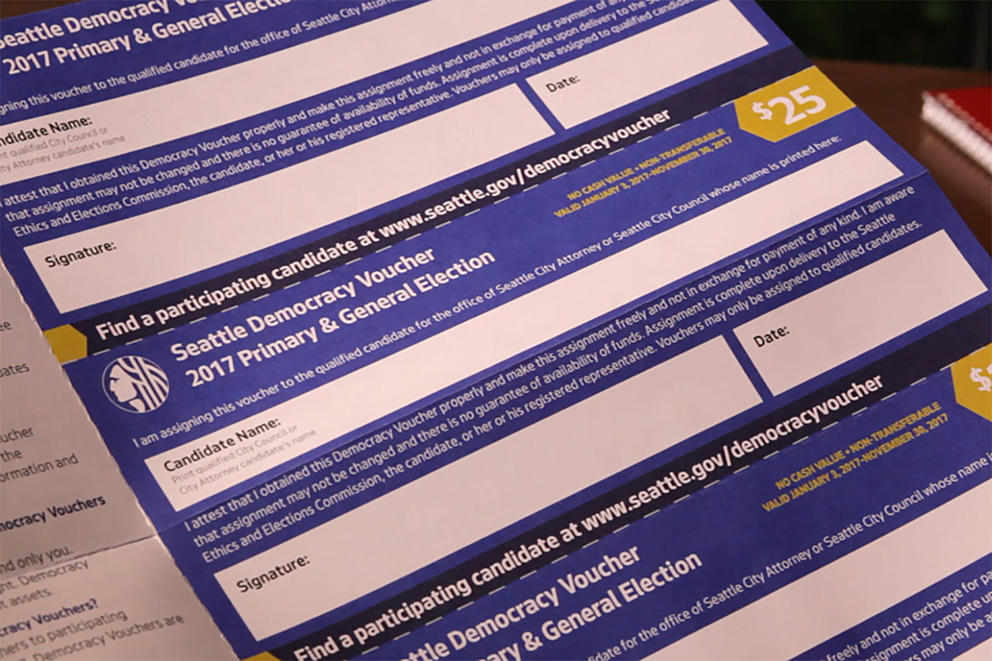

The program sends each eligible Seattle voter four $25 vouchers, which they can then give to city-level candidates of their choice. By approving the program in 2015, local voters made Seattle the first U.S. city to implement this type of public financing of campaigns.

Dan Nolte, a spokesman for the Seattle City Attorney’s Office, said the ruling could help clear the way for more cities in the state to adopt similar voucher programs. “This is a big win for the changing face of political campaigns, opening the playing field to provide more people an opportunity to seek local office,” Nolte wrote in an email Thursday. “If other Washington cities were considering a Democracy Voucher program of their own, they’ll be aided knowing our state’s highest court has just given the green light.”

The democracy voucher program is paid for by $3 million per year in property taxes. That’s what caused two Seattle property owners, Mark Elster and Sarah Pynchon, to challenge its constitutionality in 2017.

Their argument was that, by funding the program through a property tax, “The City of Seattle compels property owners to sponsor the partisan political speech of city residents,” according to their initial complaint.

A King County Superior Court judge dismissed the suit, rejecting Elster and Pynchon’s claim that the program violates their First Amendment rights to free speech.

In its unanimous ruling Thursday, the state Supreme Court agreed with the King County judge’s earlier decision.

“The Democracy Voucher Program does not alter, abridge, restrict, censor or burden speech,” Justice Steven González wrote on behalf of the court’s nine justices.

Ethan Blevins, an attorney representing Elster and Pynchon, said his clients are still deciding whether they might petition the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case. “I think it’s quite likely,” he said.

If they choose to go that route, there’s no guarantee that the nation’s highest court would decide to give the case another look, however.

Heather Weiner, a campaign consultant who worked on the initiative that created the program, said Thursday’s ruling was not surprising.

“That initiative had been reviewed with a fine-tooth comb by state and national lawyers,” Weiner said Thursday. “We knew it was absolutely legal.”

Seattle voters approved Initiative 122, dubbed the “Honest Elections Seattle” ballot measure, by a vote of 63% to 37% in 2015.

This year marks the second time democracy vouchers are being used in local Seattle elections after the program went into effect in 2017.

Blevins, the attorney for the Seattle property owners, said if his clients decide to seek a review by the U.S. Supreme Court, they’ll renew their argument that they have a right to abstain from funding political speech they disagree with.

Blevins said he disagrees with the Washington court’s conclusion that there’s no free speech problem, merely because his clients “aren’t individually associated with the message they are being required to fund.”

“They feel like they’re being required to front the money for someone else’s campaign contributions,” Blevins said. “I think that just feels demeaning, to be required to sponsor viewpoints they object to, especially in the context of elections.”

Weiner said the initiative already has been a success in terms of getting more people to participate in local elections. She said the voucher program, along with the city’s 2015 redistricting effort, has been a factor in this year’s broad array of Seattle City Council candidates. More than 50 people are running for council seats this fall, as several incumbents have decided not to seek re-election.

One recent academic analysis found the democracy voucher system was successful at increasing the number of Seattle residents who contribute to campaigns.

People across the country have taken notice of the program, including Democratic presidential candidate Kirsten Gillibrand. The New York senator has introduced a public campaign financing plan for federal races that is modeled after Seattle’s program.

Certain cities, including Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Austin, Texas, also have considered implementing democracy voucher programs of their own.