And we’d better do it fast. Seattle’s official goal of reaching carbon neutrality by 2050 was adopted long before last fall’s United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report gave us little more than a decade to cut global emissions in half. The city should be revising all of its goals and plans in light of this new assessment, but, in the meantime, we’re not on track to meet even that target: Seattle’s emissions are rising, not falling.

The climate crisis demands a radical shift in what wonks call “mode split,” replacing drive-alone trips with public transit, carpooling, biking, walking and rolling. Of course, there are good reasons why some people need to drive alone some of the time: stocking up on groceries, bringing tools to a worksite, hauling garden supplies, rushing the dog to the vet. This makes it all the more important that discretionary drive-alone trips, the ones that could be replaced by other ways of getting around, take a steep nosedive. So how do we accomplish that? Exhorting or shaming individuals to change their habits is seldom more than marginally effective. Major behavior shifts can happen quickly, but only by changing the options, incentives and disincentives that shape people’s everyday choices — as well as their big choices, like whether to own a car. This is a common good problem that only government is in a position to solve. It calls for visionary leadership from the city, and, in particular, from the mayor.

Editor's note: This is Part 1 of a two-part Op-Ed examining transportation. Read Part 2 here.

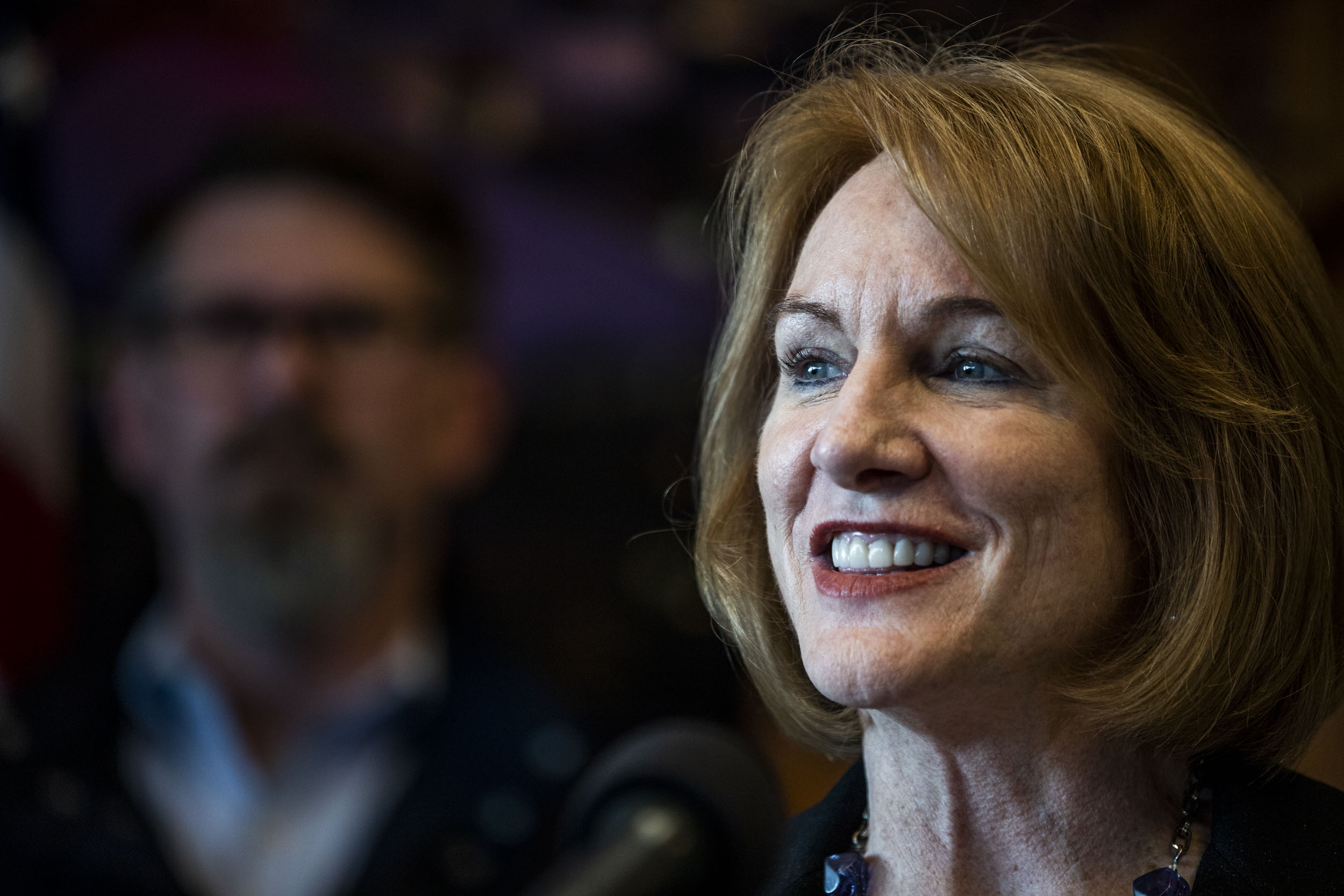

Does Mayor Jenny Durkan have a vision for reducing emissions from transportation? In fact, last April she announced a big idea that many transportation and climate advocates found surprising and exciting: congestion pricing — charging fees for driving that more accurately reflect real social and environmental costs. Over a year later, the city finally released a study that outlines some options and challenges, including the need to design a system that doesn’t disproportionately impact people of color and lower-income drivers who may not have viable alternatives.

Designing a plan that’s equitable and effective is a challenge, but an even bigger one may be simply coming up with anything that voters will support. The only U.S. city so far poised to implement congestion pricing, New York, has a population density and a mass transit system in the European league, leaving Seattle’s in the dust; it also suffers from gridlock and transit infrastructure woes (which revenue from a pricing scheme can address) that are orders of magnitude worse than ours. There’s reason to fear that without a great leap forward in noncar travel options — especially public transit — congestion pricing in Seattle may end up being too heavy a political lift.

If Durkan is serious about overcoming this obstacle to her big idea, her record so far doesn’t show it. No doubt the mayor inherited some real difficulties, but a series of major setbacks has given advocates good reason to be frustrated. Overoptimistic budgeting and a highly competitive construction market left the Move Seattle levy far short of delivering on all its promises of transit, bike and pedestrian infrastructure. The mayor reacted by walking back these promises, reassessing what levy funds can build and trying to recalibrate public expectations. As a result, plans for seven RapidRide bus lines have been delayed or shelved and crucial connections in the planned citywide bike network have been left unfunded. Other mayoral actions, like pulling the plug on 35th Avenue Northeast bike lanes, have left many people questioning her commitment to transcending car culture, or even to prioritizing safety over the loud voices of some neighbors and businesses.

Fiscal responsibility is important, but it doesn’t constitute a vision for the transportation system Seattle actually needs to meet our climate, safety and mobility goals. Vision in hand, we can be realistic and smart about prioritizing existing resources, and then figure out what additional funds are needed and how to raise them. Incidentally, an inspiring overall vision, and the will to explain and build support for that vision, are also what’s needed to overcome many of the neighborhood-level conflicts that can sink good projects.

Suppose congestion pricing fails to materialize. What’s left of Durkan’s vision? When she announced her climate agenda last April, one more transportation idea made the cut: electric vehicles. With our state’s plentiful clean hydropower, we should speed electrification of the city, delivery and personal vehicles that will continue to be necessary, and the mayor’s leadership on this is welcome. But ultimately, electric cars are an even less sturdy hook on which to hang a green urban transportation vision. They do nothing to reduce traffic. Moreover, building two-ton metal exoskeletons for the masses is a carbon-intensive industry and will remain so for some time, even if the cars themselves are emissions-free. Electric vehicles are a sidekick, not the hero in our sustainability saga.

I don’t envy the mayor — or city council members or city staff — the job of navigating today’s “disruptive” and disrupted transportation industry. From platform technologies like Uber and Lyft, to bike and scooter share, to smart cities and autonomous vehicles, those are some choppy waters. It must be hard to do more than react, and, of course, the city has to react, and regulate, and adapt. But the mayor’s job in such circumstances is also to lead, to chart a course that ends in a future city we all want to inhabit. And that means not getting too distracted by the shiny new things, not neglecting the actions that must be taken now in order to dramatically shift how people will choose to travel around our city five and 10 years from now. In Part 2, I lay out a four-point plan for Seattle’s transportation revolution.