Often seen as pie-in-the-sky impracticality, prison abolition has become more visible in recent years. That growing attention owes in part to decades of often behind-the-scenes work by abolitionists working to shrink the scale, size and scope of state punishment. Although often misread as a one-time event that closes every prison, prison abolition is a process. Its grand vision — what abolitionists Gilmore and James Kilgore describe as “a society that centers freedom and justice instead of profit and punishment” — is implemented in a myriad of efforts to transform how the government treats people and how people treat each other. Abolition is both a goal and a strategy. Rather than ignore reforms, abolitionists pursue the kind of small-scale changes and alternatives that can add up to larger transformations.

That Washington would play such a pivotal role is not surprising, given that the state has often played a vanguard role in criminal justice policy — often for the worse. Washington was the first state to enact three-strikes sentencing policy in 1993 and blocked state funding from going to educate incarcerated people before the federal government cut Pell Grants to prisoners. Washington has been out front on everything from the eradication of parole to juvenile life without the possibility of parole (tried as an adult at 14 years old, Tacoma’s Barry Massey was the youngest person sentenced to life without parole in 1987; he was released in 2016, after the Supreme Court ruled mandatory life sentences for juveniles unconstitutional). For decades, the state has implemented civil commitment and expanded punishments for people convicted of sexual offenses, which have grown while prosecution for drug offenses has fallen. Built in the early 1980s, the state’s “Intensive Management Units” have become a national model for “administrative segregation” — a technocratic term for long-term solitary confinement.

Any discussion of the state’s checkered history of imprisonment must pass through the Washington State Penitentiary, better known as Walla Walla. When it opened in 1887, Washington was still a territory and not yet a state. The prison’s opening was itself an act of prison reform: it replaced the brutal convict leasing camps, where early industrialists paid local sheriffs to then rent prisoners to work for free in slavelike conditions. As with the more notorious convict leasing system in the South, the forced labor of prisoners in Washington was steeped in abuse and violence. The outcry led the territorial government to respond by taking over the practice of punishment; the response was Walla Walla prison.

Warden Douglas Vinzant, a champion of prison reform during his brief tenure at Walla Walla, addresses prisoners who completed high school and community college programs at a graduation ceremony in the Big Yard. (Photo by Ethan Hoffman, taken at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla, Washington, 1978-1979. Courtesy of the Washington Prison History Project and UW Bothell Digital Collections.)

Chronically overcrowded and underresourced, Walla Walla has always been the crown dungeon of the Washington penal system: the end of the line, a medieval homage to harsh punishment that, as journalist John McCoy recently observed, “serve[s] no one.”

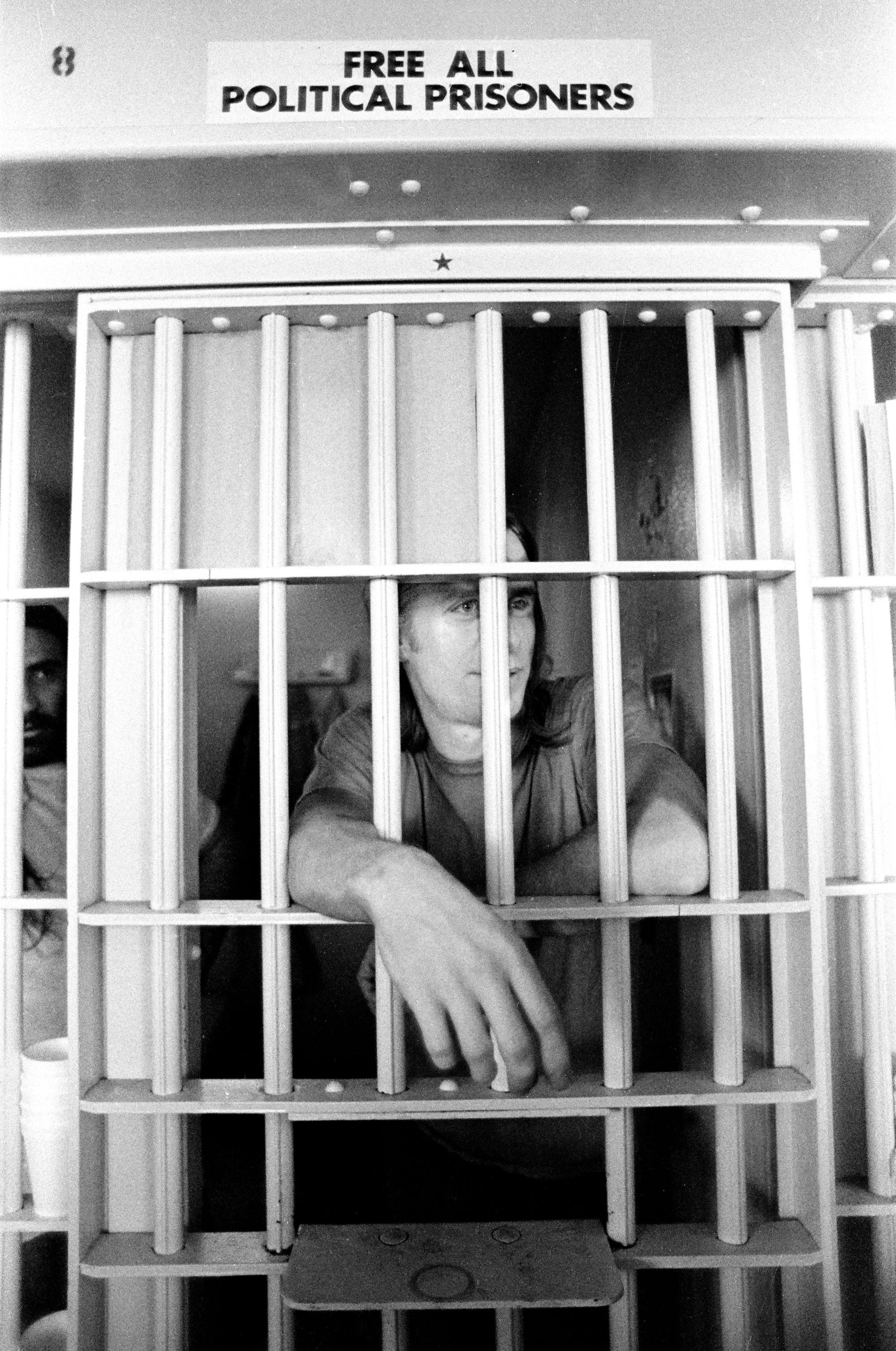

Prisoners have responded to the terrible conditions there with a creative urgency. In the early 1970s, Walla Walla debuted an innovative experiment in prisoner self-governance that also won some small liberties — less censorship restrictions, extended telephone and visiting privileges, the opportunity to wear civilian clothes. While some of the liberties remain, none of the governance does. As Washington, like other states, embraced a punitive backlash, it lengthened sentences, built more prisons and further disempowered incarcerated people.

Isolated and embattled, abolitionists nonetheless carried on. Throughout the closing decades of the 20th century, abolitionists and their allies remained focused on protecting human rights for incarcerated people, particularly those already marginalized by gender or tribal affiliation. Two examples of what abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba has described as ‘participatory defense campaigns’ stand out here: feminists, Native Americans and other activists rallied on behalf of Yvonne Wanrow (now Yvonne Swan), a citizen of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, after she killed a man who tried to attack her and molest her and her neighbor’s children. Over nearly a decade of trials and appeals in the 1970s, the Wanrow case expanded women’s legal right to self-defense against gender violence. Between 1979 and 1981, similar coalitions rallied in defense of Jimi Simmons, a Muckleshoot-Rogue River man accused of killing a guard following a series of riots and reprisals at Walla Walla. Simmons was acquitted and eventually freed from prison. (His brother, also incarcerated at Walla Walla, was convicted of the murder.)

In the 1980s and 1990s, incarcerated people and their supporters networked through prisoner publications. In 1987, a group of radical prisoners at the Washington State Reformatory in Monroe began publishing The Abolitionist, a monthly newspaper documenting prison policy and prisoner activism. One of the editors, Ed Mead, was incarcerated for his role in the revolutionary George Jackson Brigade and had edited a series of radical newsletters in prison. After two years, The Abolitionist became Prison Legal News, which remains a vital resource on contemporary prison issues. These publications were some of the only consistently critical looks at the Washington criminal justice system, always attentive to the ways people could work to better conditions.

More recently, abolitionists have been involved in a variety of campaigns to shrink the scale and scope of Washington’s prison system. Perhaps most successfully, advocates succeeded in abolishing the state death penalty. The road to its abolition — years of grassroots organizing that resulted first in a gubernatorial moratorium, followed by a lawsuit that led the state Supreme Court to rule it unconstitutional for its “arbitrary and racially biased” application and finally a legislative ban — suggests something of the patience, dedication and tactics of abolitionists.

They are also busy. Prison is an amorphous concept, including city and county jails, state prisons and federal detention centers. For Washington, that entails everything from juvenile incarceration to immigrant detention. Abolitionist campaigns have targeted structures that maintain or extend the scale of punishment locally, regionally and nationally.

At the local level, abolitionists have been working to stop construction of a controversial $210 million new youth jail in Seattle’s Central District. While supporters of the jail say a new building will provide needed services to incarcerated youth, opponents challenge the practice of putting young people in cages. Following years of petitions, protests and civil disobedience, groups involved in the No New Youth Jail Coalition have advocated a moratorium on construction and demanded that King County “repurpose the site for meeting the needs of youth and families.”

Statewide, abolitionists have worked to end life without parole, implement meaningful programs that provide for people’s education and reintegration in society, and implement transformative and restorative justice practices that provide accountability for interpersonal harm. Many of these efforts have involved incarcerated people partnering with their free-world allies on everything from providing higher education to incarcerated people and working to reintroduce parole (and as a community-led rather than law-enforcement-led process) to peer mentorship programs. The efforts of community groups like API Chaya and the Formerly Incarcerated Group Healing Together join those of prisoner organizations like the Black Prisoners Caucus and the Women’s Village.

Nationally, Washington is home to the region’s largest immigrant detention center. Though the state has publicly rebuked a number of Trump administration policies, the state nonetheless is heavily involved in a punitive response to immigration. Abolitionists have worked to shut down the Northwest Detention Center, block deportations (using both civil disobedience and legal aid), support people on hunger strike there and free people held there or at the Federal Detention Center in SeaTac (including a number of women who the Trump administration had separated from their children at the border). Washington activists have been central to the national movement to abolish ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) and succeeded in stopping ICE from using Boeing Field for its deportation flights.

Left to its own devices, prison reform tries to fix prison with more prison: from the construction of Walla Walla to replace convict leasing to the use of life without parole sentences as an alternative to the death penalty. And so perhaps the greatest interventions abolitionists make is to challenge the narrow horizons of existing reform: documenting, for instance, that life without parole is not an alternative to the death penalty, but an extension of it (and one with similarly racist disparities), or that the state’s alternatives to Donald Trump’s xenophobia still allow the Department of Corrections to cooperate with immigration enforcement. In debates about agency budgets, governmental infrastructure and social priorities, abolitionists can be found working with verve, clarity and all-due urgency.