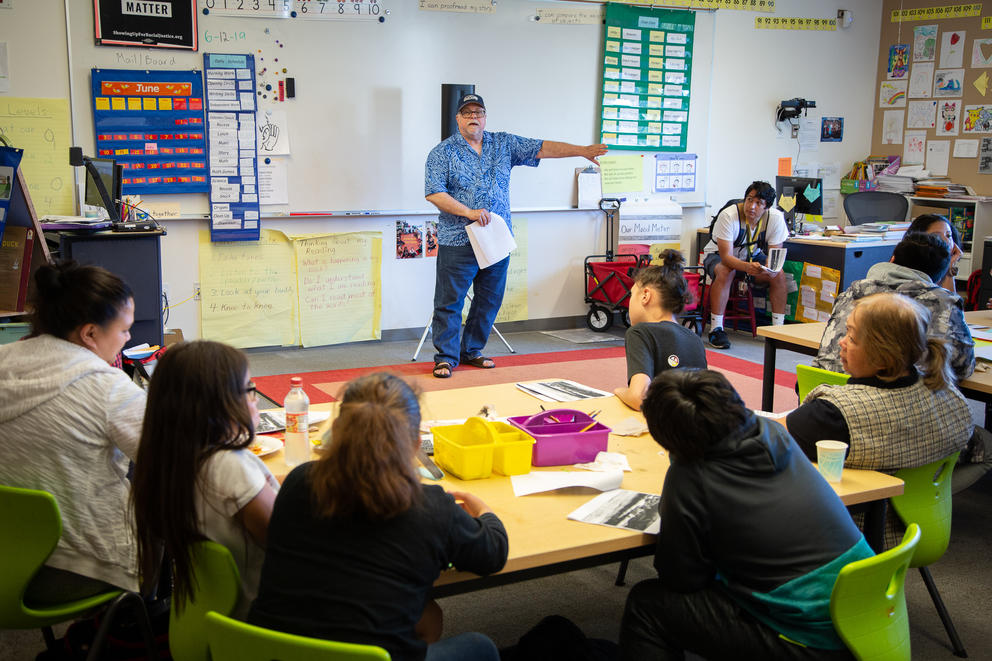

Speer disputes the contention that the first Americans migrated to the Pacific Northwest 5,000 years ago, referencing recently discovered evidence of human life on the continent that dates back several dozen millennia. He recounted for those gathered what Native societies in the Puget Sound region were like prior to colonial influence: Tribes accessed an abundance of food from both land and water, extended families lived together in wooden longhouses in the spirit of intergenerational collaboration and environmental stewardship was paramount.

He then moved on to more sensitive subjects. He pointed to the class systems and intertribal slavery that existed between First Nations people. He went on to describe the devastating impact of smallpox brought to the Americas and cited estimates that about 90% of First Nations people perished in the years after that first contact, mostly the result of either disease or violence inflicted by European colonizers.

“I’m here to teach you about the things you won’t learn in school,” Speer said.

This is the kind of Native-focused learning UNEA has brought to Seattle students since its founding in 2008. But soon, these educational sessions at Licton Springs will end. A letter sent to UNEA June 5 by Seattle Public School officials notified the organization that its time at Licton Springs was coming to a close. The group has been directed to have all of its property removed from school premises by Aug. 15.

The alliance was founded by Native American community organizers to help close gaps in educational opportunities and outcomes for Native students. Seattle Public Schools officially signed on in 2013. The partnership resulted in UNEA bringing the Clear Sky Native Youth Council after-school program to Licton Springs, which formerly was Pinehurst K-8, and Robert Eagle Staff Middle School.

The two schools share a building, with Licton Springs touted as a Native heritage option school and Robert Eagle Staff as a neighborhood Highly Capable Cohort (HCC) pathway school for students identified as academically gifted. Native American students make up approximately 12% of Licton Springs’ student body, while at Robert Eagle Staff they’re less than 1%.

More than 800 students and volunteers participated in the Clear Sky program during the 2017-2018 school year, with as many as 30 participants showing up to the twice weekly sessions. All students who regularly engage with the Clear Sky program go on to graduate, according to Sarah Sense-Wilson, the organization's board president.

State data show that the four-year graduation rate for Native American students in Seattle Public Schools has been on an upward trend since 2013, improving by nearly 23% as of 2018. Additionally, there has been significant progress in the collective performances of Native American students on statewide assessments in the district. UNEA representatives insist the organization has played no small part in this upswing.

“We take a holistic approach,” Sense-Wilson said. “It's not just about doing your homework, but about connecting [students] to their roots and tradition, teaching them practices that really help them develop their … sense of community.”

Reasons for the termination outlined in the letter from SPS to UNEA include an alleged failure by the organization to provide impact and attendance data district leadership requested, making it out of step with school board policy and superintendent procedure pertaining to community-based partnerships.

In a statement provided to Crosscut, SPS officials echoed much of what appeared in the letter: The district values the work UNEA does to support Native youth and families, but the group has neglected to align its goals and practices with those of SPS.

UNEA leaders say they “vehemently dispute” the district’s stance, and maintain that they have furnished all documents SPS officials requested. Additionally, they’ve pointed to instances they say would amount to the district violating its own partnership agreement terms.

"Our good faith effort to cooperate, collaborate and engage with [Robert Eagle Staff and Licton Springs] has been stunted by SPS leadership as evidenced by [the district’s] unwillingness to communicate with our UNEA staff and UNEA Board,” representatives of the organization wrote in a response letter to SPS on June 9.

UNEA members also allege a failure by the district to follow through on previously agreed upon quarterly meetings, and say volunteers have been treated poorly by school officials.

While leaders of UNEA say they were blindsided by the termination of the partnership, tensions between the organization and the district have been brewing for some time.

“There was a promise from [former] Superintendent José Banda’s administration that there would be a commitment to keeping space for the Native community in SPS,” Sense-Wilson said. The former superintendent had publicly vowed to consult Native American community members regarding next steps in Native-focused education amid the closure of the American Indian Heritage High School, which officially shut its doors in 2014.

Sense-Wilson said that while SPS made good on its commitment to name a school in honor of Robert Eaglestaff, the late Lakota community leader and American Indian Heritage principal, the district’s decision to make it an HCC pathway school — a program that attracts a predominantly white and affluent student body — has effectively gentrified the school. Enrollment at the school is nearly 60% white.

The district originally planned for Robert Eagle Staff Middle School to seat 1,000 students. But in 2013, the school board revised facility plans to add Licton Springs to the Robert Eagle Staff campus. Currently, enrollment at Robert Eagle Staff exceeds the building’s capacity as a result of a growing number of students in the area and more children being identified and placed in the school’s HCC program.

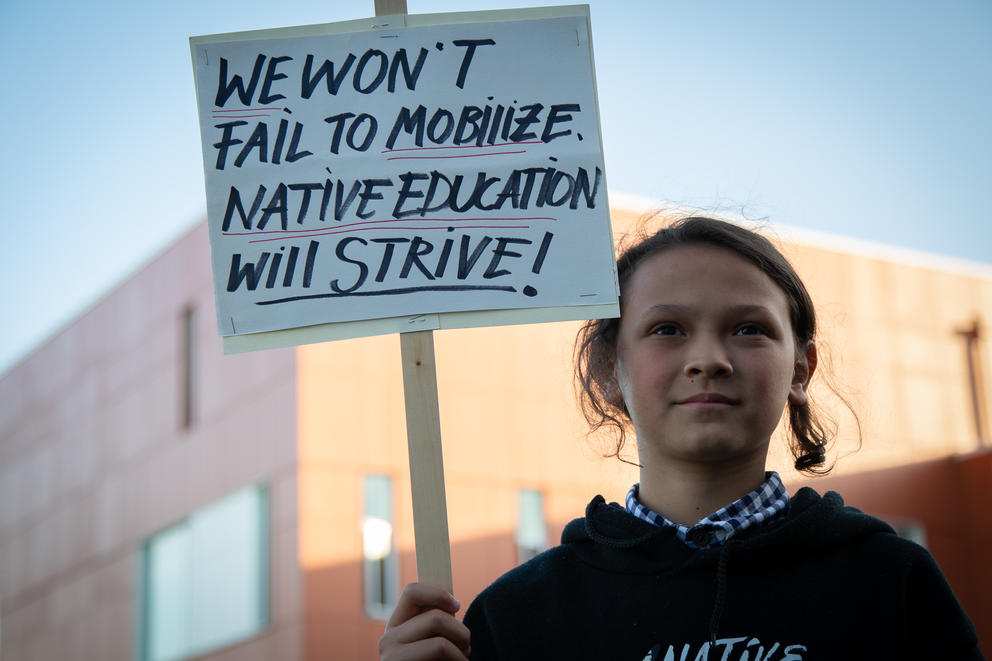

Recent talks among SPS officials about potentially reducing Licton Springs to a K-5 school or merging it with nearby academically accelerated elementary school, Cascadia, has caused more concern among supporters of Native-focused education. Another option would be moving Licton Springs from its current site in the north end Licton Springs neighborhood to the Webster Elementary School building in Ballard, which is slated to reopen for the 2020-2021 school year.

SPS Superintendent Denise Juneau said at a June 6 work session for student assignments transitions that while there seems to be a lot of excitement around the idea of Native heritage programs in the community, “nobody could say, ‘This is what makes us Native-focused.’”

Sense-Wilson rejects this sentiment and asserted that moving Licton Springs would be especially devastating, considering the spiritual significance of the school’s location to the Duwamish tribe.

“All of this that is transpiring is triggering a lot of stress and trauma for our community,” she said. “To me, it's a reenactment of historical experiences of being displaced and discarded and dishonored. How things have been mishandled is really concerning to me.”

Moreover, Sense-Wilson contends, the termination of UNEA’s partnership with SPS is antithetical to the district’s recently adopted 2019-2024 strategic plan. The plan pledges to “unapologetically address the needs of students of color who are furthest from educational justice,” including students of Native American heritage. Although they make up less than 1% of the district’s population, Native American students are disciplined at a rate of 7.34% — the highest of all racial demographics in SPS.

“We don't represent the entire community and we understand that,” Sense-Wilson said. “Our community is one of the most complex and diverse of any cultural group. But UNEA has been a consistent supporter of Native education in Seattle. We are an authority and a strong voice around this issue.”

UNEA members plan to lobby the Seattle School Board at its next regular board session on June 26 to restore the organization’s partnership with Licton Springs.