The case hinges on two questions: Would the tax be legal under laws previously set by the state Legislature, and would the tax be legal under the state’s constitution? For decades, the answer to both questions has widely been accepted as “no,” but the city, in a Hail Mary effort, is hoping to change that.

Doing so will require something of an uphill battle.

That is largely because of a pair of decisions from the state Supreme Court in a 1930s ruling that income is property, a designation that, in effect, bars municipalities from putting graduated rates on varying incomes and precludes efforts to tax wealthier residents more. This was no secret when Seattle passed its income tax. In fact, it was a well-recognized part of the city’s strategy: Approve the tax and hope the Washington Supreme Court responds by overturning its previous decision.

Also at issue is a 1984 state law that bars local jurisdictions from taxing “net income,” another barrier to an income tax. The city is hoping that this law will be ruled unconstitutional.

The city’s efforts have been stalled since King County Superior Court ruled a year and a half ago that the tax is neither constitutional nor allowed under state law. After losing its case before the Superior Court, the city asked to send it directly to the state Supreme Court. But that plea was rejected and it landed in the Court of Appeals.

In Thursday’s hearing, Judge James Verellan questioned why the Court of Appeals should even listen to arguments when only the Supreme Court can overrule its own precedent. Attorney Paul Lawrence, arguing on behalf of the city, said the lower court should first seek to answer the question concerning the legislative barriers before sending constitutional questions to the higher court.

Lawrence and Claire Torney, an attorney for the Economic Opportunity Institute, made several arguments in favor of the tax. First, that the income tax was not really an income tax — and was in fact closer to the sorts of taxes imposed on businesses or in local improvement districts, where taxes are imposed in exchange for some specific benefit.

The attorneys also argued that state law did, in fact, allow cities like Seattle the authority to impose taxes because of contradictions within state code and because the law apparently barring income tax is overly broad.

Rob McKenna, attorney for the plaintiffs, said any argument that the tax was something other than an income tax was false, as evidenced by the language of the 2017 law and the accompanying campaign, which explicitly referred to it as an “income tax.” Additionally, he argued that state law was not conflicted: When the 1984 law was passed, he said, legislators were clear they were banning cities like Seattle from imposing an income tax.

McKenna did allow that, thanks to the 1930s Supreme Court decisions, a tax could possibly be imposed on income in the same way it’s imposed on property, but that would bar the city from taxing some residents at higher rates than others and severely limit the amount that could be taxed.

The three-judge Court of Appeals panel is expected to issue its ruling in the coming weeks or months.

Regardless of how the judges rule, the case is likely to be appealed to the state Supreme Court, where, if accepted, the court could address its decisions from the 1930s. The ascension of the matter to the state’s highest court has long been assumed; the city hopes that this case could undo the earlier rulings. Yet, even if the city manages to upend judicial precedent, it still must contend with the state law.

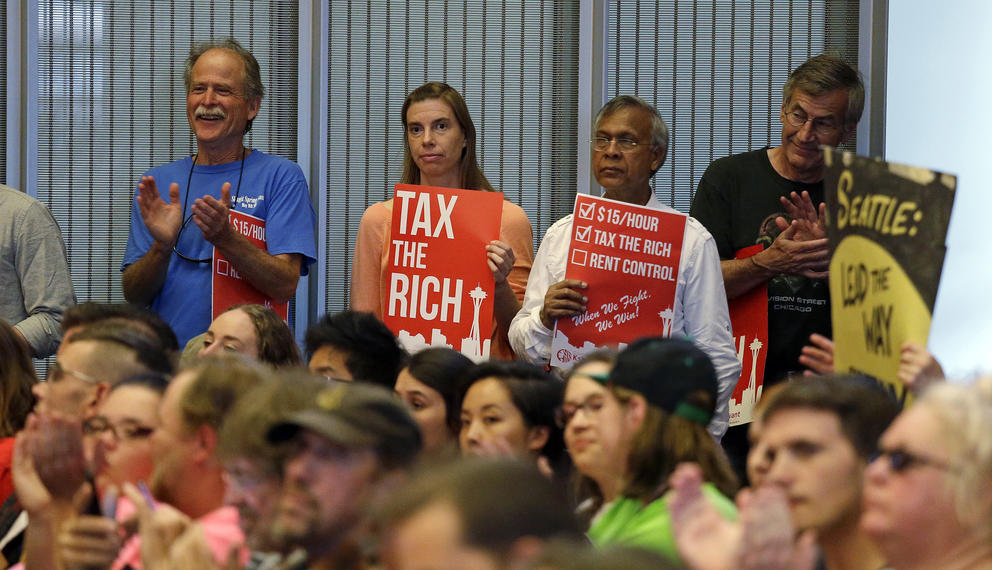

Seattle passed its 2.25 percent income tax on all personal income over $250,000 in the summer of 2017. It did so in an effort to generate more revenue — as much as $140 million a year — at the peak of a housing and homelessness crisis.

Had the tax been put into place when the city passed it, the first collection would have occurred last April. However, that has clearly not occurred and is unlikely to occur any time soon — if ever.