The practice of turning away Section 8 holders or other prospective renters because of their source of income was banned in Washington state by the Legislature during its 2018 session. The new rules kicked in last September.

Yet Kalani is proof that while turning away Section 8 vouchers may no longer be legal, it still happens. And unless Kalani wants to find a lawyer to bring the landlord to court — a towering task, especially for someone without stable housing — the state does not offer help with enforcement of the law.

Kalani said four separate landlords in south King County rejected her over the past month explicitly because she was receiving federal Section 8 assistance. In two instances, the landlords even put it in writing.

One wrote “No Section 8” on the top of the Craigslist advertisement for an apartment.

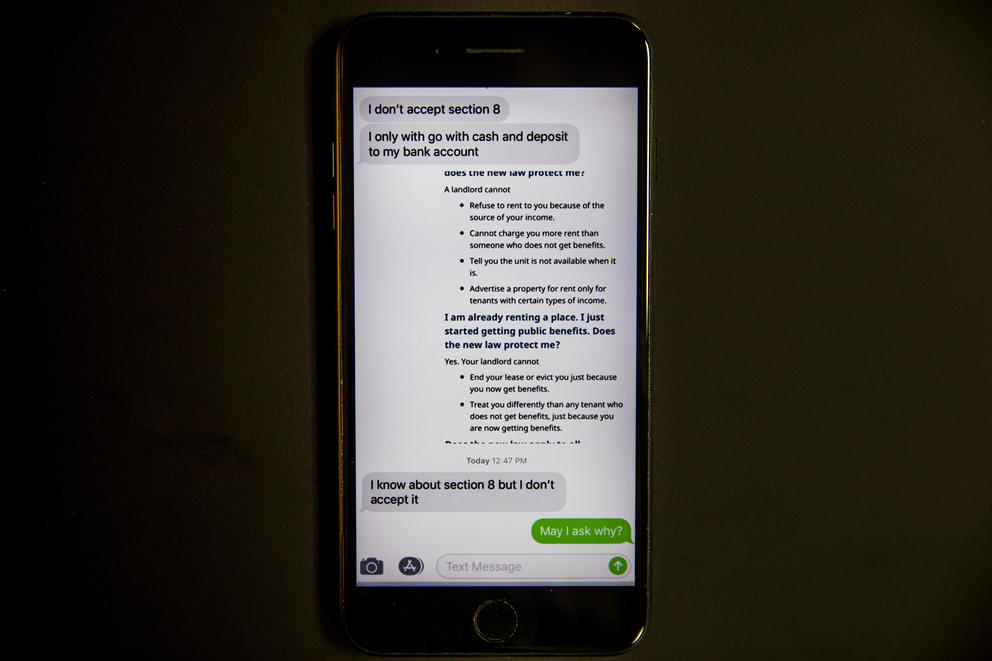

On another occasion, Kalani texted her interest to a landlord. The landlord responded, “I don’t accept section 8. I only with [sic] go with cash and deposit to my bank account.” When Kalani sent a screenshot of Washington’s law, the landlord wrote, “I know about section 8 but I don’t accept.” Kalani asked why, but never heard from the landlord again.

“It’s been so frustrating and it makes me mad because you made me waste my time,” said Kalani. She added, “They passed a law but they’re not enforcing it. So how can we look for a place if you guys aren’t going to help enforce it? What’s the point of even calling?”

In Seattle, it’s been illegal to reject Section 8 vouchers for more than 25 years. The city expanded those protections to other sources of income in 2016. That same year, Renton banned source-of-income discrimination as well.

But the practice remained legal in other parts of the state until late 2018, after the Legislature passed a bill that instituted the new ban on income discrimination by tucking it into the state’s Residential Landlord-Tenant Act.

“It was essentially a loophole in the fair-housing act that previously a landlord could say, ‘I don’t take this kind of subsidy or that kind of subsidy,’” one of the bill’s co-sponsors, Rep. Nicole Macri, D-Seattle, said in an interview. “This makes clear that if you have money to pay rent, you should be considered for a unit. The color of money you’re bringing should not exclude you from consideration.”

Under the new law, landlords may not reject qualified tenants purely because they receive local, state or federal funding to pay rent. If a landlord is found to have violated the rule, that property owner is liable for up to 4½ times the monthly rent, plus court fees and attorney costs.

The law also created a mitigation fund for landlords to dip into if any damage is done to their units while renting to a Section 8 holder.

Housing advocates had been pushing for a bill of this type for at least 10 years, said Michele Thomas of the Washington Low Income Housing Alliance. But the issue only recently gained traction in Olympia as the state’s widening housing struggles have forced more lawmakers to confront the issues.

“It’s a central issue of justice,” Thomas said. “It’s seen as a civil rights issue; it’s seen as a central plank in eliminating homelessness. I think as lawmakers have learned more about this … and how much housing instability impacts people’s lives, there’s been a growing awareness about and more support for housing tenant protections.”

The steep fines and guarantee of reimbursement for attorney’s fees were meant to create enough of a disincentive to landlords and a path for tenants to take them to civil court, said Thomas. But because of its place in the Residential Landlord-Tenant Act, it’s on tenants like Kalani to pursue their own cases.

“It’s a self-help act, so there’s no enforcement agency,” said Thomas. “That’s a big flaw with the Residential Landlord-Tenant Act.”

Currently, lawmakers have little sense of whether any tenants are actually challenging landlords under the new rules. “On the enforcement piece, we need to probably get a sense from our housing advocates of how many people are following through,” said Rep. Marcus Riccelli, D-Spokane, the primary sponsor of the bill. “At this point to try to get the numbers, unless someone’s self-reporting, it’s hard.”

For Macri, the preferred option would be a separate office, similar to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or Labor and Industries, where tenants could bring complaints and from where officials could carry out proactive testing.

Thomas agreed. “Having an agency enforce it is a good idea, it just costs money,” she said.

Sean Martin of the Rental Housing Association of Washington acknowledged that some landlords may be unaware it’s not legal to deny Section 8. He believes it’s because some landlords don’t rotate through tenants very often, leaving them out of date when it comes to laws. “It’s tough because, particularly smaller landlords, their rental property is not what they see as their primary business,” he said. “If they get someone in the unit … they just don’t understand that stuff changes a lot more regularly than they’re used to.”

Martin’s organization has sought to educate landlords — via outreach sessions, its newspaper, media spots — but Martin said it can be difficult to reach everyone. And for that reason, he favors a light touch early for the law, so as not to punish small landlords for not understanding the rules yet.

“I think that getting voluntary compliance is the most helpful at the outset,” he said.

When it comes to tenant protections, enforcement is always a challenge. Seattle’s Office for Civil Rights is tasked with ensuring the city’s ban on income discrimination is upheld, but its resources are limited. The office occasionally will carry out testing operations — filling out identical applications with only protected classifications changed. During its last test in 2017, when it came to familial status, disability and source of income, the office identified a difference of treatment in 110 cases, levying small fines on 25 landlords.

For Kalani, the task of finding a place was made doubly hard by the size of her family. Her four children span from a 1-year-old to her teenage daughter and, as Kalani put it, “my kids are loud.” So to be rejected just because of her voucher made a challenging search worse.

After looking for nearly two months, Kalani finally found a place earlier this month in south King County. She’s worked as a certified nursing assistant med tech in recent years and hopes the stability that comes with housing will allow her to return to school.

“I made a promise to myself that I would go back to school to pursue my medical career,” she said. “I don’t want to be wiping butts all my life. I want something better. The Section 8 is helping me get better for my family.”