She had read on social media that two federal agencies — U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) — were increasingly staking out local courthouses. She didn’t quite believe the rumors. Still, she felt uneasy.

The next day, as the couple turned a corner near the courthouse, she spotted a white SUV. “La migra,” she thought. Her hands turned cold.

“I said, ‘It’s them,’ ” but he didn’t believe me, she said, referring to her partner of almost a decade. At the end of her boyfriend’s DUI hearing, a man in jeans and a black top whom she suspected was an immigration official rushed out the door, in front of them. As they walked out, the man called out her partner’s name, shoved him to the floor, flashed a badge and handcuffed him, she said. The man turned out to be a U.S. Border Patrol officer. He and one other Border Patrol agent escorted her partner to the SUV.

“We have kids, please,” she can be heard saying to the officers in a video of the arrest obtained by Crosscut. “I get you’re doing your job, but we have five kids at home. What am I going to tell them?”

“Just let me give him one more hug, please,” she pleaded.

Lydia told Crosscut that, other than the DUI, her partner had never been in trouble before. The DUI occurred after a going-away party last year for the orchard crew her partner supervises. “He regrets that day so bad,” Lydia said in a recent telephone interview. Her partner had managed to turn his life around after the DUI, she said, rededicating himself to the family and attending church regularly. Now he sits at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma.

In an interview from the detention center, her partner said the officers had made fun of him and his family, referring to them as "crybabies," on the way to the jail in Spokane before arriving in Tacoma days later.

“They are treating the people they are picking up like garbage,” Lydia said.

Kenneth Chadwick, a former cop turned attorney who is a supporter of President Trump, filed a formal complaint with Border Patrol after officers at the courthouse recently “manhandled” and frightened his client.

“I would be scared, too, if two plainclothes people just grabbed me,” Chadwick said. The officers threatened Chadwick himself with arrest, he said, for simply asking questions, such as whether they had a warrant.

When Chadwick asked one of the officers to explain to his client in Spanish that he had the right to remain silent, one officer responded by saying, “Yeah, right.”

“To me that’s over the top,” Chadwick said. “They just walk up to brown people and say, 'Hey who are you?'”

“I was pretty baffled. I’ve described their conduct as bounty hunter like,” he said, “wholly the most unprofessional police work I’ve ever seen from federal agents.

“I know what good law enforcement is supposed to look like. This wasn’t it.”

In response to questions, Stephanie Malin of Customs and Border Protection, said “the men and women of CBP are committed to treating those with whom they come into contact with professionalism, dignity and respect while enforcing the laws of the United States. CBP takes allegations of misconduct seriously, and investigates all formal complaints.”

The detention has severely impacted Lydia and her family. She said her children have taken to sleeping in the same bed as she. They barely have an appetite. One daughter has suffered from nightmares.

“I cry every night before I go to bed. I just stay strong for my kids,” she said.

Lydia was lucky in one sense. She was able to witness her partner’s arrest. Others have had loved ones leave for court and never return. Families are left searching frantically for them, as they would in a missing persons case, before discovering they’ve been detained or deported.

Because immigration officials are often in plainclothes and in unmarked vehicles, some who have witnessed an arrest mistakenly believe they’ve observed a kidnapping and have called 911, said Genia Blaser, an attorney with the New York-based Immigrant Defense Project.

U.S. courthouses have become the latest battleground for immigration enforcement. Experts and advocates say courthouse arrests became more frequent in 2017, after the Trump administration announced its planned expansion of immigration enforcement, which included the hiring of 15,000 additional ICE and Border Patrol personnel and plans to make good on his campaign promise to build a wall on the country’s southern border.

In a memo the following year, ICE clarified its stance on courthouse arrests, explaining it would limit its immigration enforcement actions inside federal, state, and local courthouses to only certain people, such as gang members, those with criminal convictions, or people who pose national security threats. Family members or friends accompanying an undocumented immigrant would not be targeted unless they attempted to interfere, ICE said. The memo reasoned that “courthouse arrests are often necessitated by the unwillingness of jurisdictions to cooperate with ICE.”

"The increasing unwillingness of some jurisdictions to cooperate with ICE in the safe and orderly transfer of targeted aliens inside their prisons and jails has necessitated additional at-large arrests," the memo noted. “In years past, most individuals arrested at a courthouse would have been turned over to ICE by local authorities upon their release from a prison or jail based on an ICE detainer.”

Immigrant advocates argue that the expansion of ICE and Border Patrol arrests isn’t about countering cities’ sanctuary policies or decreasing criminal activity, but “going after the lowest hanging fruit.”

“It is completely absurd for them to try to pretend that it’s because local law enforcement won’t work with them,” said Matt Adams, legal director of the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project.

“The Department of Homeland Security is thumbing their nose at the state and local justice system,” Adams said. “All they care about is meeting their quota of arresting people.”

The Washington Immigrant Solidarity Network, a statewide coalition of immigrant and refugee rights organizations, said for the past few months the group has received an increasing number of calls through its hotline about courthouse arrests.

“It’s like the Wild West out here,” said Abigail Scholar of Central Washington Justice For Our Neighbors, an advocacy group that helps organize “know your rights” training aimed at informing immigrants that they are not required to reveal their immigration status without the presence of a lawyer. The group also offers accompaniment to courthouses and legal services. “They can get away with it because they know no one is watching.”

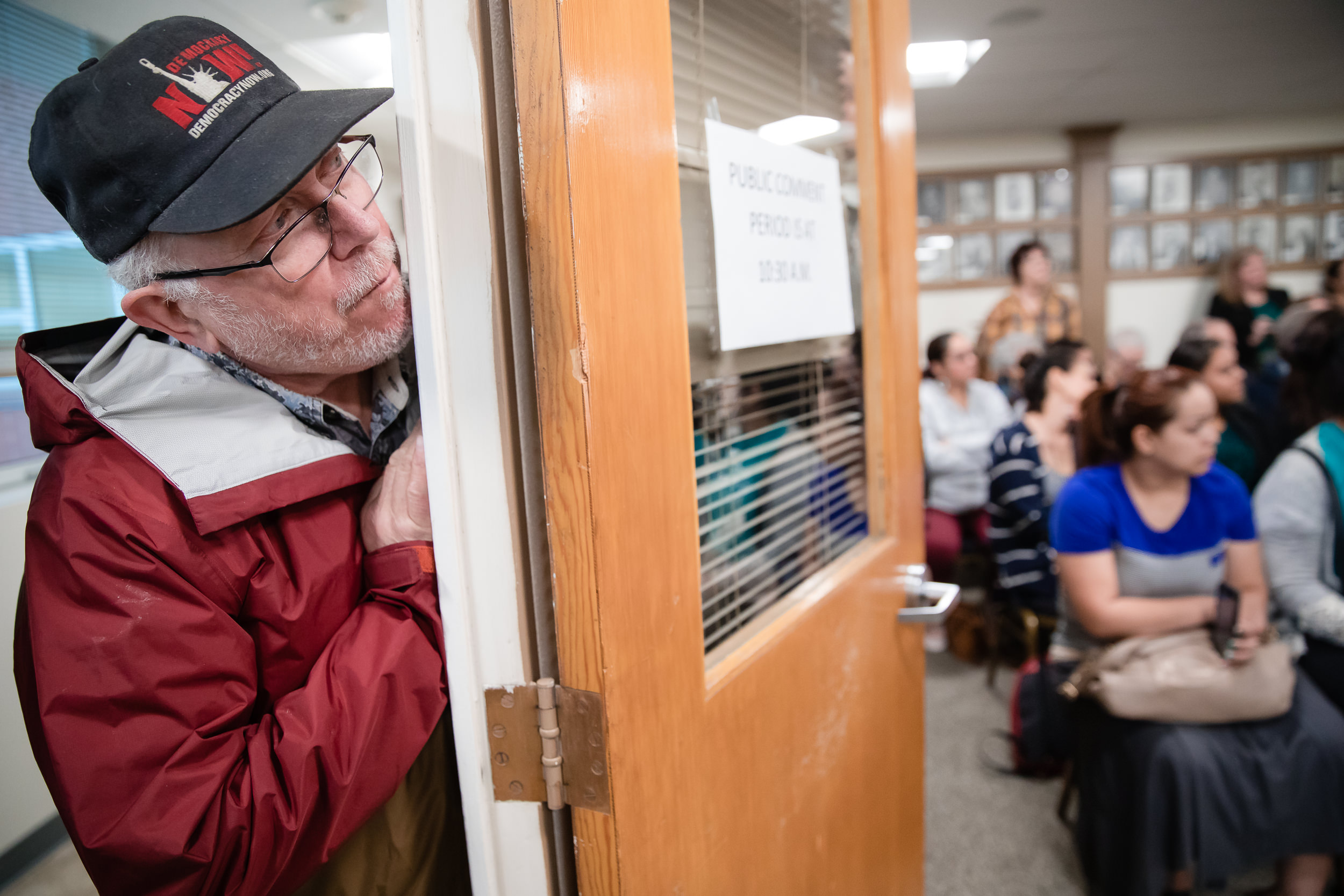

Last week, members of both the Washington Immigrant Solidarity Network and Washington Justice For Our Neighbors confronted the Board of County Commissioners at Grant County District Court about the increase in immigration arrests. Grant County Sheriff Tom Jones said he had been unaware of the presence of immigration authorities. He promised to look into the matter.

Some advocates have pointed out that Border Patrol agents seem to be operating far from the border — outside a 100 air-mile zone. But Adams explained Border Patrol has the authority to conduct searches and make arrests far from the border so long as they have probable cause. Within 100 miles of the border, agents have expanded authority, or even more leeway in making arrests and conducting searches.

In response to questions, the Border Patrol maintained it has the authority to operate nationwide. In addition, Tanya Roman, a spokesperson for ICE in the Pacific Northwest, said many of those targeted “at or near courthouses are foreign nationals who have prior criminal convictions.”

“Absent a viable address for a residence or place of employment, a courthouse may afford the most likely opportunity to locate a target and take him or her into custody,” she said. “In such instances where deportation officers seek to conduct an arrest at a courthouse, every effort is made to take the person into custody in a secure area, out of public view, but this is not always possible.”

But advocates say immigration officials do not always, as they claim, target criminals. Often, those targeted are at court for minor offenses, such as a traffic ticket, or to serve as a witness. One person living in Quincy told Crosscut he was arrested after attempting to register his car in his name. He said the only time he had run into trouble with law enforcement in the past occurred years ago, when he was caught driving without a license and insurance.

Experts say ICE can decide who it is targeting any number of ways, including through cooperation with police, FBI databases and court schedules that are publicly available at some courthouses. There have even been reports of prosecutors turning people over to immigration authorities and officers eavesdropping on conversations between an attorney and a client.

In a civil rights complaint filed last year by the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project, one person reported an ICE officer “intentionally eavesdropped on my conversation with my defense attorney in the Clark County Court in Vancouver, Washington.”

“My criminal defense attorney came into the courtroom and called my name. I followed him out of the courtroom, and I noticed a man in plainclothes follow us out of the room,” wrote the person who filed the complaint. For privacy reasons, Crosscut is keeping the person anonymous.

“I sat on a bench with my attorney in the waiting room and spoke with him about my case. I noticed the same man who followed us out of the courtroom sitting across from us and listening in to our conversation. The same man arrested me after I left the courthouse, and he told me he heard everything I said to my attorney.”

The complaint went on to note: “The officer described this conversation as between me and ‘court staff,’ when it was only between my attorney, the court interpreter and myself. This violated attorney-client privilege and my constitutional rights.”

The Washington Defender Association, which has been tracking courthouse arrests, received a report last year from one public defender with two clients who were arrested for driving without a license.

“We believe the Quincy Police Department is profiling our clients and arresting them. ...They take their fingerprints at the jail and then release them. Then they contact ICE and tell them when their court date is, which is when they come pick them up. This is unconfirmed, but based on recent actions this seems to be a pattern," the public defender reported.

When asked about the public defender’s accusation, Capt. Ryan Green of the Quincy Police Department said “that’s not our policy.”

“We’re not letting them know court dates. We’re not doing any of that,” Green said. Quincy police do cooperate with ICE, Green said, but only if they have "an active warrant for somebody.”

There have been local efforts to curb immigration arrests at courthouses. In 2008, King County Superior Court issued a policy on such arrests, noting that “courts must remain open and accessible for all individuals and families to resolve disputes under the rule of law.” Arrests based on immigration status, the court said, would not be allowed unless directly ordered by a judge or because public safety is at risk. Seattle Municipal Court has the same policy.

More recently, in 2017, Washington state Supreme Court Chief Justice Mary Fairhurst wrote to the Department of Homeland Security, noting that there had been reports of courthouse arrests in a number of Washington counties, including Clallam, Clark, Cowlitz, King, Mason and Skagit.

"These developments are deeply troubling because they impede the fundamental mission of our courts, which is to ensure due process and access to justice for everyone, regardless of their immigration status,” she wrote.

ICE does avoid certain spaces, such as schools and churches; the agency considers them “sensitive locations.” In her letter, Fairhurst called on Homeland Security to designate courthouses as such.

The Washington State Bar Association followed suit, becoming the first statewide bar association in the country, according to the American Civil Liberties Union, to formally oppose the increased presence of ICE agents at courthouses.

Washington state Attorney General Bob Ferguson released guidelines that same year.

“The court system relies on people coming forward in order for it to function,” Ferguson’s guidelines noted. “These principles are vital for equal justice for all.

“Thus, to the extent that the actions of ICE agents obstruct judicial proceedings, courts and judges may enforce order in their courtrooms.”

Last year, a group of immigration advocates filed a lawsuit in Massachusetts challenging the practice of courthouse arrests. The state’s highest court, however, ruled against them. That same year, dozens of former state and federal judges also advocated for ICE to add courthouses to the list of "sensitive locations.”

One particular area of concern is domestic violence. A nationwide survey conducted by the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence in 2017 found that in Washington state, 81 percent of advocates reported victims of domestic violence had expressed concerns about going to court out of fear of being arrested because of their immigration status.

A nationwide survey released in 2018, conducted by the National Immigrant Women's Advocacy Project and the ACLU, found that 82 percent of prosecutors reported that domestic violence is harder to investigate since President Trump took office. Seventy percent of prosecutors reported the same for sexual assault and 48 percent for child abuse.

Fifty-four percent of judges participating in the survey reported court cases had been interrupted after an immigrant who was a crime survivor failed to appear, fearing arrest. Some point to a notorious courthouse arrest in 2017 as an example of an immigrant’s worst fear, when ICE agents arrested an undocumented woman seeking a protective order against her abusive boyfriend at an El Paso County courthouse.

Some states have recently passed or proposed laws that limit ICE and Border Patrol activity at courthouses. The California Values Act sought to limit the extent to which state and local resources, including courthouses, are used for immigration enforcement. It was signed into law in 2017. A second bill currently under consideration seeks to "clarify the power of judicial officers to prevent activities that threaten access to courthouses," by prohibiting arrests there. New York also is considering a bill, named the “Protect Our Courts Act,” which would require a warrant signed by a judge before anyone could be arrested in or outside a court.

Advocates hope Washington will consider similar legislation, possibly as part of the Keep Washington Working Act, which aims to prohibit local and state law enforcement from questioning people about immigration status and facilitating civil immigration enforcement. The bill recently passed the state Senate.

But the trend of courthouse arrests has continued, including in other parts of the country. In a report released earlier this year, the Immigrant Defense Project noted that arrests of undocumented immigrants in and around New York courts have increased by 1,700 percent. The total number of arrests reported in 2017 and 2018 numbered 374, compared with 11 in 2016. According to the report, ICE has also arrested family members present during operations and carried out arrests in noncriminal courts.

In one case documented in the report, two men in plainclothes grabbed a boy as he and his mother were leaving a court in Brooklyn, dragging him to an unmarked vehicle. Fearing she was witnessing her son’s kidnapping, she repeatedly asked the two officers who they were but didn’t get a response. A third officer shoved the woman against the wall, causing her head to hit the wall. He repeatedly told her to “shut up.” The mother was left sobbing on the street, the report said.

Meanwhile, in Washington state, Lydia is caring for her family, a task made more difficult because she suffers from fibromyalgia and cannot drive. At the certified nursing assistant job she’s had for more than a decade, she makes only a little over minimum wage. Her partner, too, had been loyal to his job, she said. In fact, his boss had recently written a letter on his behalf, referring to him as reliable, diligent and hardworking. He was in line to receive a promotion.

She tries to call him as often as she can, sometimes three to four times a day, spending as much as $40 on phone calls on a daily basis. She said she thinks about every penny that she spends, knowing the legal costs associated with his case will add up.

“It’s like if they do everything in their power to cut you out from your family completely,” she said.

Matt McKnight contributed reporting to this story.