Four human steps away, now also under glass in the same exhibit, are artifacts of the contributions that my father, Harlan “Buzz” Reese, made to the first moon landing with his own human hands. These are photographs and maps that guided Aldrin and his fellow astronauts to the moon, and showed where they might like to walk around when they got there. Boot prints left in lunar soil memorialize the famous few who made those strides; Dad’s smeared fingerprints and careful mapping marks are a down-to-earth tribute to the other 400,000 humans beings whose efforts made the journey possible.

Now people waiting in line will get to see these artifacts, too. Seattle’s Museum of Flight is hosting Destination Moon, an exhibit of Apollo 11 treasures from the Smithsonian collection that has been traveling the country.

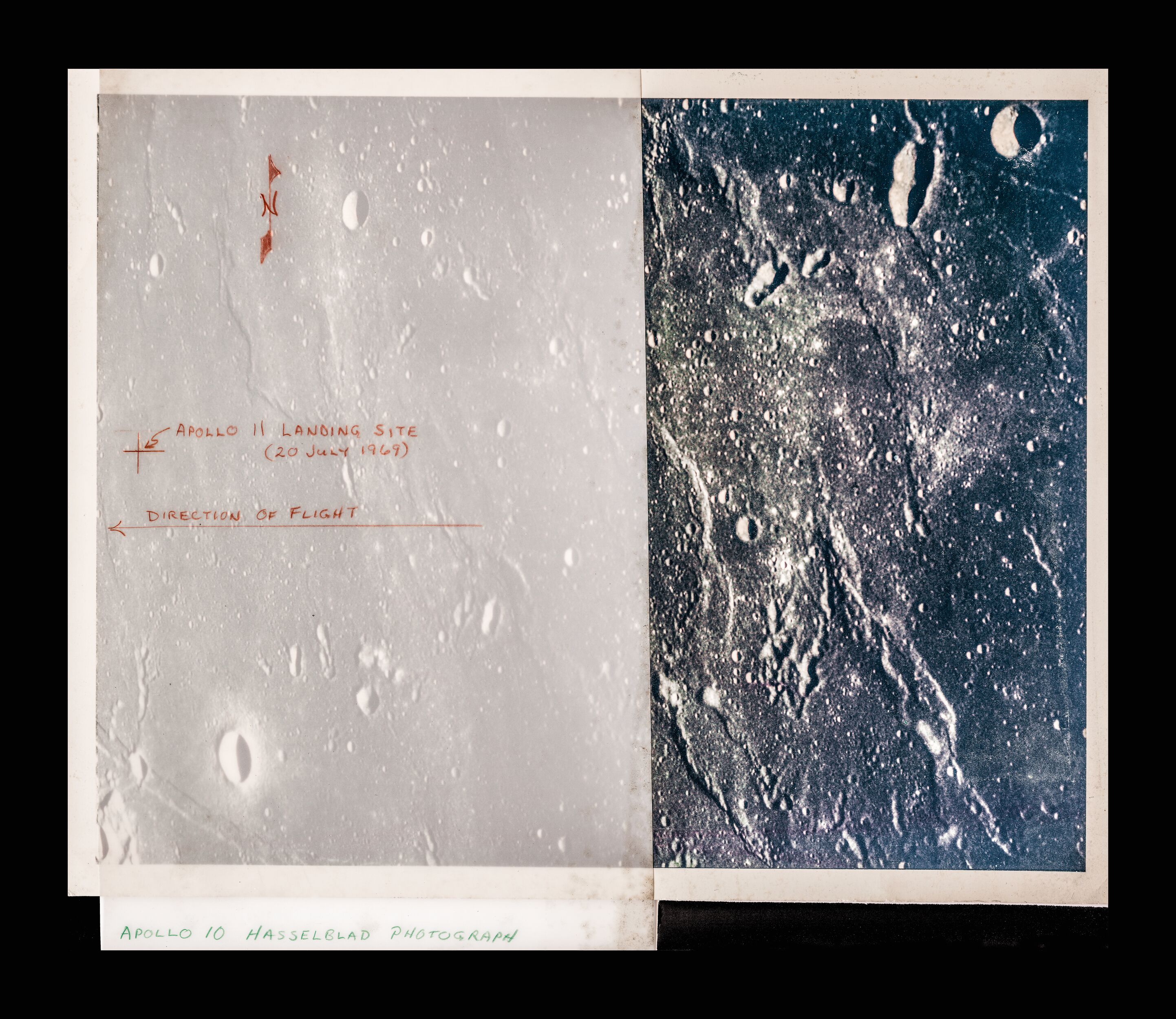

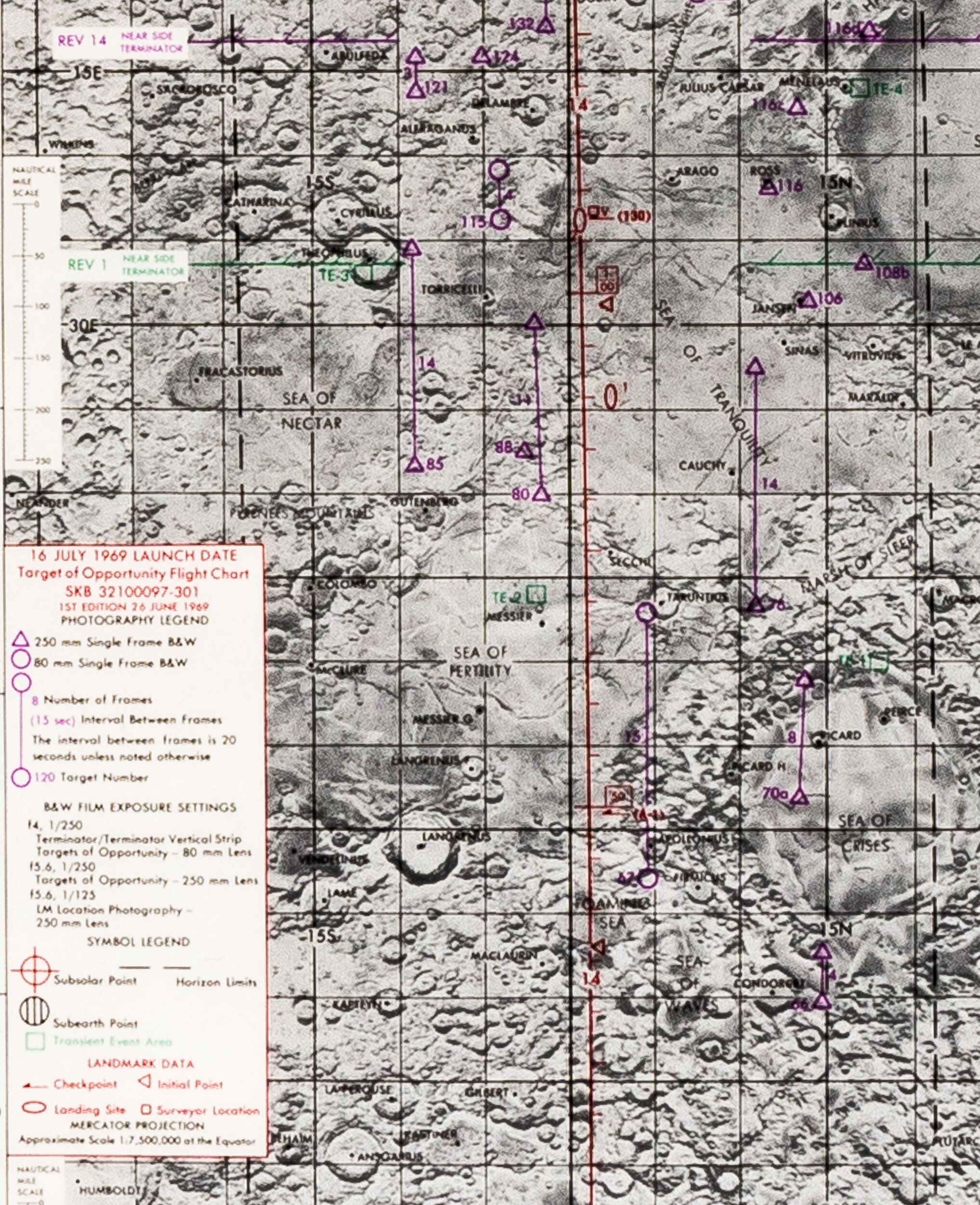

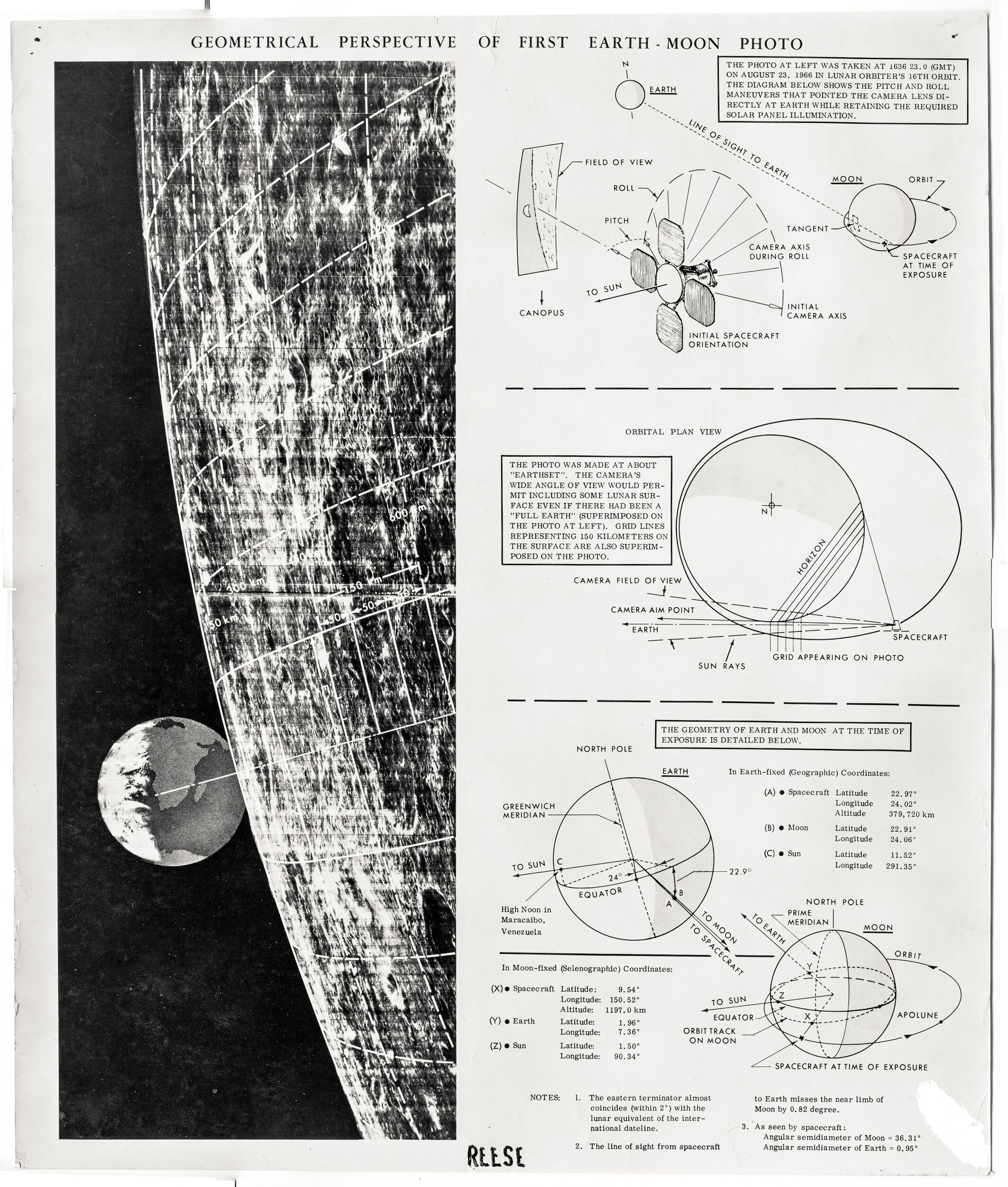

Curators in Seattle have added some gems, including Dad's. Among the items are a hand-marked landing-site photo, charts showing the descent path of the lunar module, a lunar orbit chart and a poster explaining the science behind the famous image that showed us the Earth as seen from the moon for the first time. Destination opens here April 13 and runs through Sept. 2, with extra hoopla on the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing on the moon.

That was July 20, 1969. Remember?

If we were alive nearly 50 years ago, we were very likely among the 530 million people around the globe glued to the TV or many more leaning close to a radio when those famous black, white and gray flickerings took shape in our minds and those fuzzy words between precise beeps filled our insides with wonder. If we first arrived on Earth after that time, we probably have the experience and “memory” embedded in us anyway, largely thanks to the images chosen for us, the greatest hits culled from tens of thousands of pictures recorded during Apollo missions.

“All memory is individual, unreproducible — it dies with each person,” Susan Sontag wrote. “What is called collective memory is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds,”

If only memories were more reliable, like photographs. But even trustworthy photographs are not merely documentation; they tempt us to reassemble lived experiences that have become lost to time. Narratives change according to our present needs, and so do we.

More and more obituaries proudly mention that dad or mom, uncle or aunt or dear sibling helped the men who won the space race and first landed on the moon. Dad was part of the constellation of dedicated people whose work was given new, urgent purpose for more than a decade: a mission from the president of the United States to work hard for the good of all mankind. Five years ago my own graveside words for him included such a tribute.

* * *

On a shelf in our parents’ garage, Dad left us a number of cardboard tubes and boxes, his collection of photographs, maps and charts, some slightly yellow and curled at the edges, all still possessing mesmerizing detail and mystery.

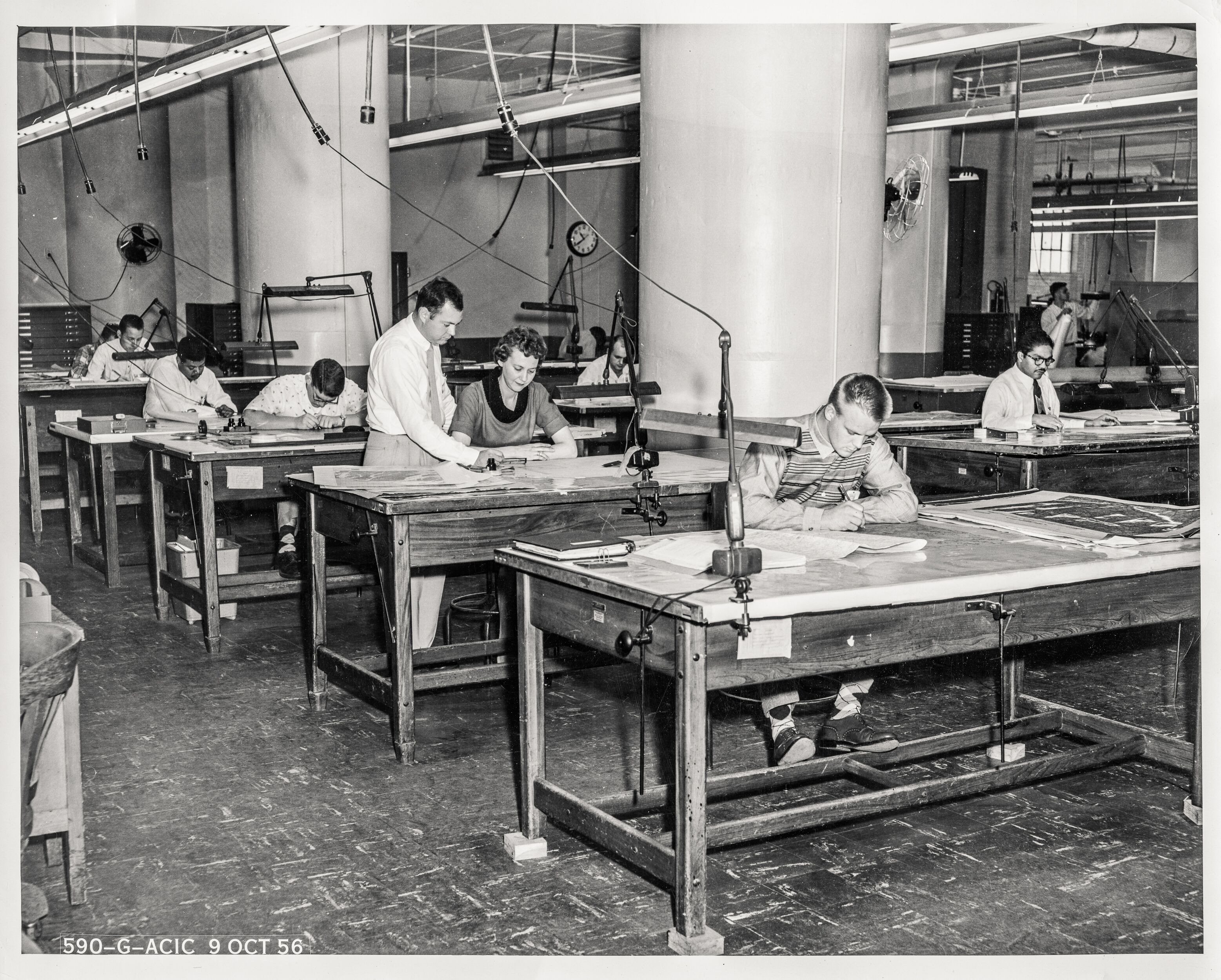

Dad made and managed these maps upon which NASA would rely. He had a long career as a cartographer, engineer and boss at the Aeronautical Chart and Information Center in St. Louis. My brother and I think he hung on to those artifacts with a sense of pride in a job well done, in case his boys might one day find them interesting and maybe even precious. We also know we come from a long line of farm folks who saved every scrap of food, repaired every broken tool and always seemed to find good uses for them.

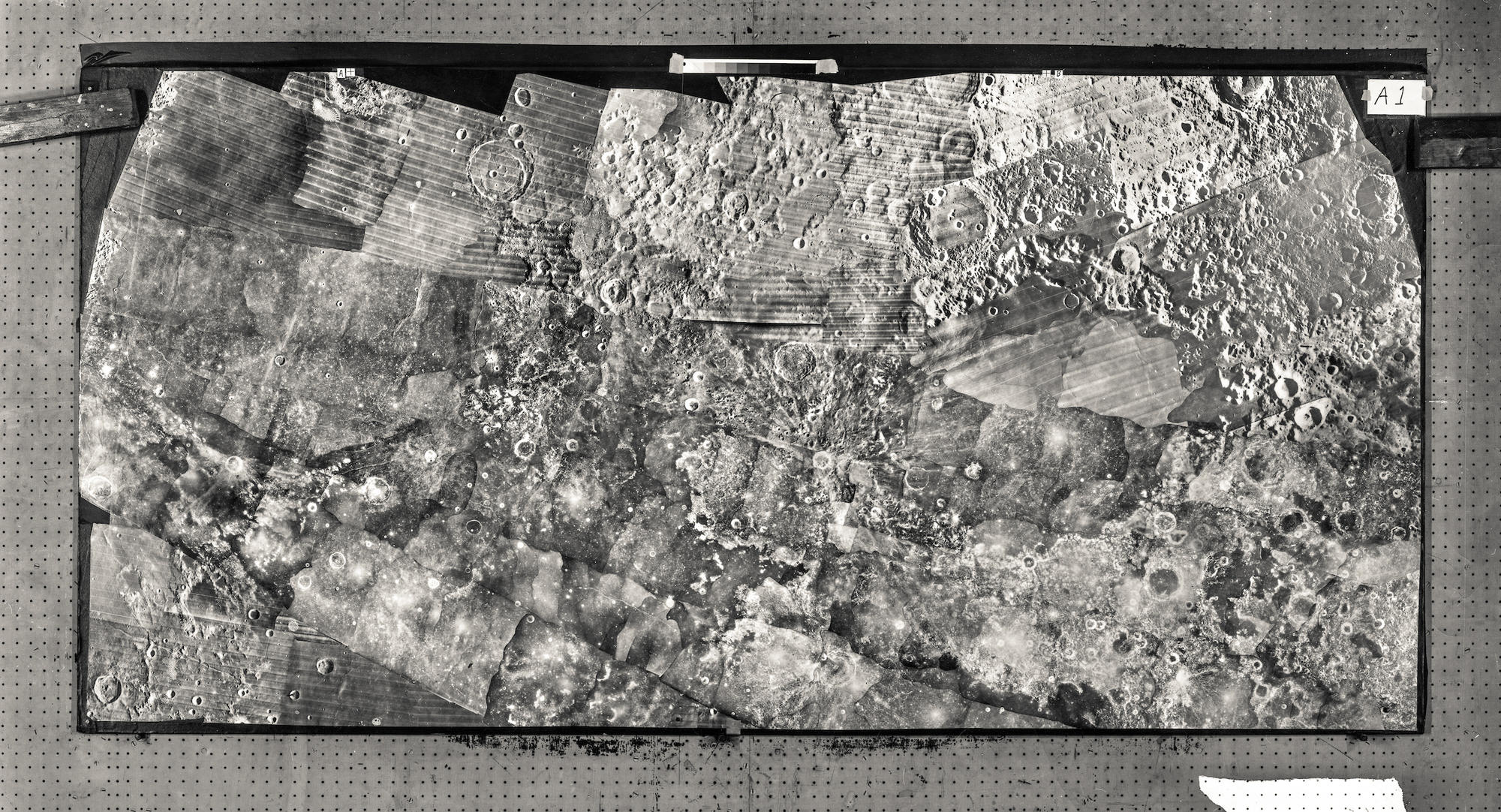

One box has odds and ends of early lunar photography, some of the prints overlain with Dad’s hand-drawn compass points, landing site X's and handwritten notations. The images were made through large telescopes on Earth, by the Surveyors and Rangers and Lunar Orbiters and early Apollos flying around and over the most promising landing sites. You can also see those smudged fingerprints that likely belong to Dad, mixed with those of many others who used magnifiers and X-Acto knives to carefully slice apart select sections of crater fields. Some small globs of cracked glue remain where they dripped during the process of pasting together the cut pieces to form mosaics of the unexplored landscape.

Some small indentations probably show how the prints were positioned in viewing devices like the extremely precise optical comparator, which helped human eyes interpret the length of shadows inside craters for the first time. These results were coordinated with data about altitude and lunar daylight to provide the most precise terrain measurements possible. Careful airbrushing would smooth over and fill in terra incognita with educated guessing. Finally, this data would be transformed into the precisely printed maps and charts that would help lunar lander pilots to, among other things, second-guess in real time the navigation decisions made by computers of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

* * *

Precision was key, of course, but the audacity to shoot three men packed into a rattling tin can toward an unexplored world also required calculating of the unforeseen, recognizing there is “… a limit to calculation, to plan, to control,” as author Rebecca Solnit has written. “To calculate on the unforeseen is perhaps exactly the paradoxical operation that life most requires of us.”

One attempt at precision was the creation of those small black plus-sign marks, the nearly ubiquitous grid work of crosshairs inscribed permanently in many of the photographs. Created using a specially engraved glass plate inside the cameras, the lines have a technical purpose and name: réseau. We feel their visual aesthetic too, the corners of frames inviting us in.They were supposed to help us understand the scale of the moon and its potential for visitation. Yet finding a way to comprehend the scale of mankind’s first personal contact with an alien world was beyond a challenge of the scientific. It was clearly a large-scale challenge for our psyche.

To see the lunar surface bumps and dips photographed in the oblique, in the close up and, finally, in the human perspectives, it dawns on us that those ultraharsh shadows and highlights really are the natural phenomena of this alien landscape. There is no atmosphere holding particulate or moisture that would diffuse the sun’s light and visually soften an object’s edge, no distant blue to help discern how far it could be to the next mountains or craters or how tall or deep they may really be. In the eyes of the first moon walkers and those of us looking over their shoulders, this seeming hyperclarity was nothing of the sort. What we recall clearly is its disorientation and desolation.

It was also the most scenic photo viewpoint ever. Up there is the smallish Earth floating in darkness, its thin blue atmospheric skin indiscernible; there is the incomprehensible vastness of “empty” space; and, of course, there is the interior landscape of human insignificance.

* * *

Why did they go and take us with them?

This was conquest, undoubtedly. We were out to conquer, claim and possess new territory and resources, extending into space our urge for Manifest Destiny, and to win the greatest race of all time, with its attendant glory. Those first boot prints are likely to remain for thousands of years; the formerly pristine environment is forever changed.

We were hoping for a transcendent experience, too. There was indeed a lot to transcend down here: the Cold War, the Vietnam War, our leaders assassinated, a roiling cultural metamorphosis. The grand moon shot was a mission taken up eagerly by politicians, corporate America, the military and the media, and inflamed by an extensive and profitable network of marketing and public relations efforts.

We agree that we were all in this together somehow, right?

* * *

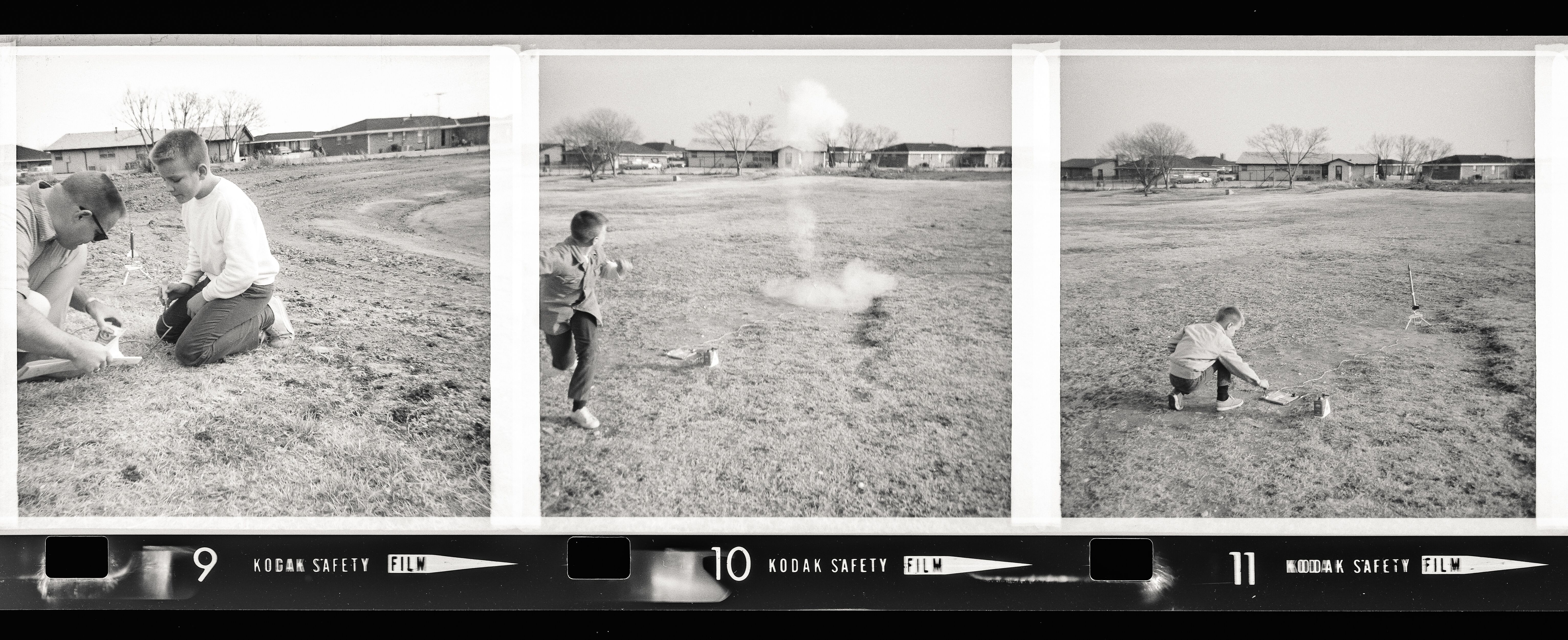

I look through these pictures and tell myself that I am still able to access a lot of what was embedded from the lunar landing in my 10-year-old hippocampus, that box of brain cells where my own repository of images and impressions are stashed. Much of the contents will be familiar to most earthlings, though there is also a folder in that archive containing some personal particulars:

Our small glowing TV screen and its slightly bent antenna, positioned literally in front of our dark living room fireplace in the suburban Midwest United States. The elbow-feel of almost-comfy green fibers in the carpet. Family members huddled together all day Sunday, with instant hot chocolate, mesmerized by those mysterious and riveting TV images and sounds. And a dawning awareness that the larger global family was gathered with us.

We treasure, and seem to need as much as ever, invitations to contemplate the relationship between humans and the rest of the natural world, the one we are most familiar with and the others for which we are just beginning to reach out. To stare as campfire light flickers in the faces of companions, then to turn our gaze beyond, deep into the stars, grasping for meaning.

* * *

Yes, we think: If only memories were more reliable, like photographs.

I wish I knew and remembered more, and could have formed a more lasting comprehension than that which my preteen self was capable at the time. I wish to be more certain about what our father and his contemporaries experienced. And I wish there were more like them still available to us.

As the first moon walkers returned to Earth, they rehearsed and did their best over the crackly communication link to express their appreciation for the multitudes who helped them reach the destination. They thanked those back home who had used their hearts, their abilities and their blood, sweat and tears to make possible the journey that, as Aldrin said, “stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all mankind to explore the unknown.”

I am grateful that those ancestors hoped to preserve for us some of their wonder. I feel sure they want us to keep passing this gift forward. Wonder is our map, helping us find the way back to where we come from, ahead to where we still might dream to go.