The next day, Eads purchased a few drawing books that the student requested and delivered them to Mary's Place. Ultimately, her interactions with the fifth grader were short-lived.

“[Homeless students’] progress is moment to moment because they aren't going to be staying at one school for very long,” Eads said. “There's really no planning for the future — that’s why you give all that you can right now."

While Eads does her best to maximize time with her students — many of whom are English language learners — she’s only able to tend to them half of the week, significantly limiting the support she can provide. And 24 middle and high-school librarians are slated to be cut to part time as the district grapples with a $39.7 million budget deficit. That would leave Seattle schools with just eight full-time librarians.

The Seattle School Board has vowed to restore the affected librarians to full-time status, but until it finds a way to do so, the cuts remain imminent.

The cuts have sparked many complicated conversations. Among them are how they could affect the district’s equity and achievement outcomes in the long run and how the state’s recent cap on local levies has affected school funding. Losing a librarian can have a large, adverse impact at a place like Northgate, where approximately one in four students are experiencing homelessness and 73% receive free or reduced lunch. Moreover, a significant portion of students require additional support in the form of special-education services. The school library serves as a refuge for these students especially, many of whom use it as a cool-down space.

Seattle Public Schools has employed elementary school librarians only part time in the past decade, compelling most to pick up additional certifications to fill other part-time positions around their buildings or at other schools; many double as technology instructors.

Eads has opted for shorter, more frequent library sessions so that she can interact with all of Northgate’s students each week. And although she gets paid to work only 2.5 days out of the week, she finds herself helping at the school on her days off — not unlike many other part-time librarians she knows.

Several Seattle students, parents and staff members have protested the cuts at recent school board meetings, sharing personal anecdotes about the positive socioemotional impact of having access to library services. A considerable body of research has linked school libraries to higher literacy, academic performance and graduation rates — all of which help reduce achievement and opportunity gaps for historically marginalized students.

The state funds 68 librarian positions in Seattle schools, although eight are currently unfilled. That money contributes to about 60% of librarian pay in the district. Local levies, grants and parent-teacher association money generate the rest of their salaries.

The librarian cuts are projected to eliminate $1.7 million of the district’s shortfall, according to a recent SPS budget report. Some of the affected schools, such as Hamilton International Middle School, expect to fill the gaps with PTA revenue and discretionary funds — the latter of which are dictated by enrollment. PTA money, on the other hand, tends to be more abundant for schools in wealthier communities.

But Craig Seasholes, a Dearborn Park International Elementary School teacher-librarian and former Washington Library Association president, said the district isn’t tapping all of its resources. He pointed out that librarians actually help their schools bring in funding through avenues like grants and book fairs.

“There are a lot of foundations in this town that can write a [$1.7 million] check,” Seasholes said. “Librarians grow the pie and that message gets lost in the cuts.”

The Legislature awarded school districts more money toward educator pay in response to the Washington Supreme Court’s ruling in the landmark McCleary v. Washington case. The Seattle Education Association negotiated what amounted to an approximately $20,000 base pay raise for most full-time librarians in Seattle Public Schools.

Although the district used a $45 million budget surplus in September to help cover the raises, some warned layoffs could be imminent if the Legislature did not increase state funding allocations or roll back its limits on local levy collecting authority.

Seasholes said he would have been content if the Seattle Education Association (SEA), the union that represents Seattle educators, had accepted a lower salary offer until a means of sustaining the pay raises was more apparent. But that’s not to say that he doesn’t support prioritizing better compensation for librarians.

“The dollar cost of a librarian is quite low if you look at how many roles a librarian serves,” he said. “It's not that we're expensive book dispensers … but if you have an instructional leader, an information technology leader, a reading advocate and a professional development provider, then actually we have a very good deal.”

Seasholes also expressed disappointment that requests for full-time librarians at high-poverty schools didn’t make it past bargaining talks. Libraries are less likely to contain resources such as modern books, updated technology and even librarians themselves if they're in schools with higher concentrations of students living in poverty than if they serve those with more affluent populations, according to a 2011 study in The Library Quarterly journal.

Both House and Senate Democrats have introduced bills this legislative session that would expand local levy authority, which lawmakers previously lowered to keep property-rich cities like Seattle from perpetuating educational inequities for less wealthy Washington districts.

Senate Bill 5313, which was passed through the Senate Ways and Means Committee April 3, would allow school districts serving fewer than 40,000 students to collect the lesser of $2.50 per $1,000 of assessed home value or $2,500 per pupil. Districts serving 40,000 or more students would be authorized to collect the lesser of the same assessed value formula or $3,000 per pupil. The levy cap would be adjusted each year for inflation beginning in 2020.

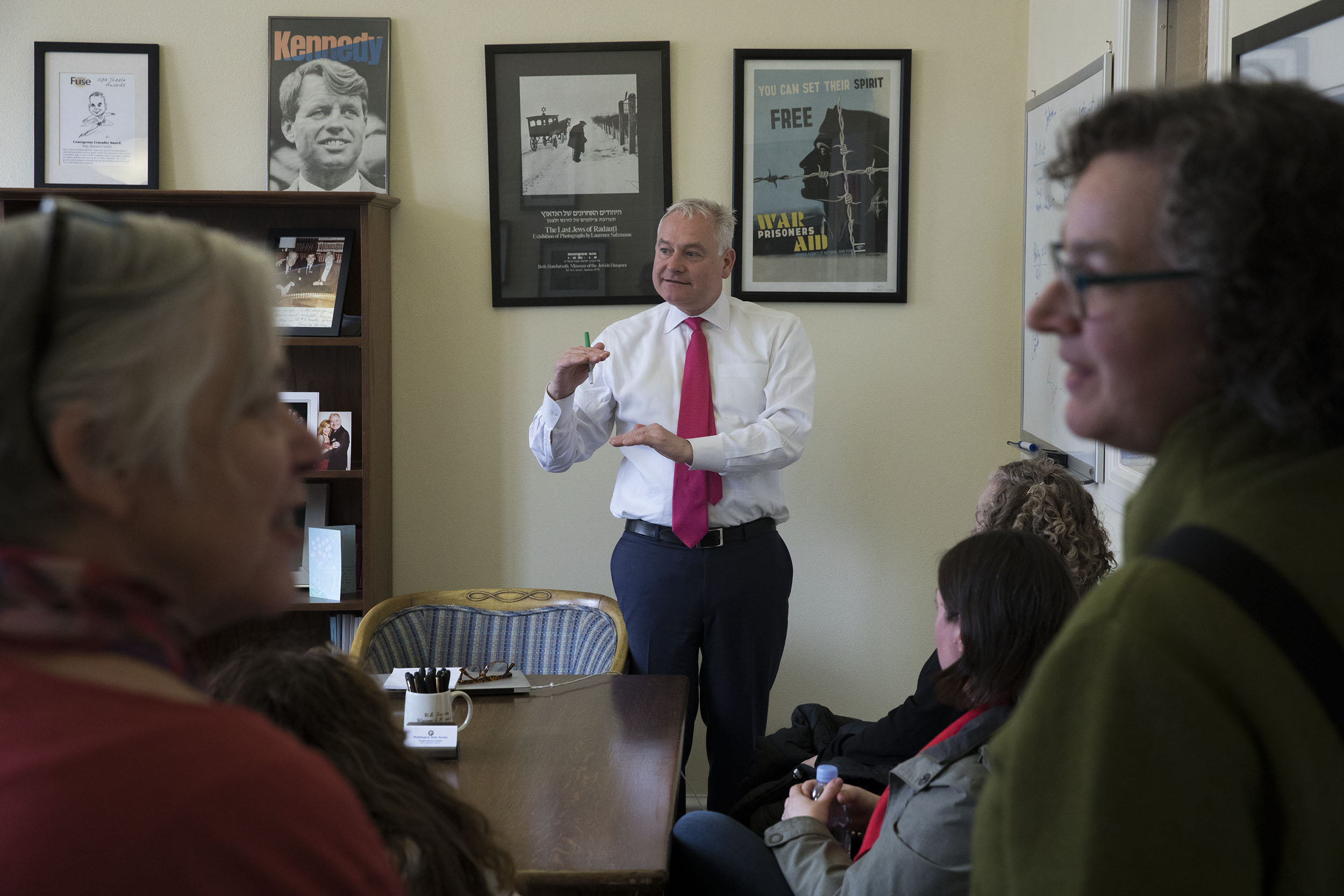

House Bill 2140, on the other hand, would raise levy-collecting authority to 20 percent of local funds, or the lesser of $3,000 per pupil or a tax rate of $1.50 per $1,000 of assessed value. A group of more than 20 Seattle Public Schools librarians and supporters traveled to Olympia this week to urge lawmakers, including Sens. Rebecca Saldaña and Reuven Carlyle, both Democrats representing Seattle, to vote in favor of increasing local levy authority — a move the librarians say is necessary to address dire short-term needs.

“The importance isn’t our positions,” Seasholes told Saldaña during a group meeting in her Olympia office on Tuesday. “It’s the students’ learning opportunities.”

The librarians also asked that the Legislature reconsider how the many facets of a librarian’s work could be factored into the funding it allocates for other services, such as special education and technology programs.

Carlyle asserted that although he doesn’t think McCleary funding reforms solved every school funding issue, the Legislature gave Seattle Public Schools a year to move away from local tax levies and align its spending with new state requirements. He maintains that the district is mostly confronting a self-inflicted structural deficit.

“We have an era of a top-down, state-centric model,” he said. “And that means that 85%-plus of the money comes from Olympia. This is the new normal.”

Carlyle made it clear that he was not value-judging Seattle’s current predicament. But he chided the district’s claims that it did not see a large increase in post-McCleary funding, citing an aggregate state increase of approximately $140 million for SPS since the fixes took hold.

Both Saldaña and Carlyle told the librarians in Tuesday’s meetings that they would support raising SPS’s levy authority temporarily to meet students’ immediate needs, but with the stipulations of greater spending responsibility and transparency from the district going forward — a complaint that SPS Board President Leslie Harris has said the district hears in earnest.

However, district officials have said there is a lack of instruction from the Legislature on how to approach the transparency asked of them. Carlyle said Tuesday that it was a “complete and total utter mistake” for lawmakers not to mandate a local spending accountability process.

Seasholes suggested that the district and the state share responsibility for funding complications.

“When Seattle points a finger at the Legislature, there are three fingers pointing back at the district,” he said. “And when the Legislature points a finger at Seattle, there are three fingers pointing back at it.”

Phyllis Campano, president of SEA, argues that if the state wants to cap levies for good, it should update its basic-education funding model to better reflect the needs of urban students.

“With our kids, now we recognize trauma that’s in their lives,” Campano said. “We have to look at a whole bunch of different factors in a child’s life to educate them. And so [lawmakers] need to revisit that formula.”

Levy reforms could take eight years to fully equalize, Carlyle estimates. He adds that legislators could assign Seattle a levy formula separate from other Washington school districts.

Campano believes individual schools should be given more control over allocating funding for staffing, basing it on the unique needs of their students — a practice she says promotes educational parity. But Seasholes argues this could exacerbate equity issues in the long run.

“It is the issue of local control that allows variations in what is considered basic education to happen,” he said, referring to decisions by Nova High School and the Center School to forgo library staff. “The nature of library is different than other instruction because it's a resource that's equitable, that's independent learning. And that role in a school is part of the definition of basic education and should be in the school.”

The state’s definition of basic education acknowledges librarians as instructional staff. However, Seattle Public Schools’ union contract for certificated employees — where librarians are represented — does not. And ultimately, the district is not legally required to employ librarians. Seasholes said he and his colleagues want to bargain for more contractual protections.

Each year, the Seattle School Board votes on whether to adopt the district’s proposed school staffing model — called weighted staffing standards — which guides funding allocations. The board unanimously vowed at a Wednesday budget work session to vote against any weighted staffing standards that fail to restore middle and high school librarians to full time. If the Legislature doesn't take action to increase the district’s funding, board members said they would somehow find $1.7 million to fill the gap. It’s unclear where that money might come from.

Librarians who attended the board meeting hailed the gesture as a victory. Others expressed skepticism.

“I will believe it when I see it,” Eads told Crosscut. “And I am also a bit ticked that they can mess with the lives of their employees and schools and then just find money to say ‘never mind.’”

Seattle Public Schools has until May 15 to notify impacted librarians of any finalized cuts.