Some 70 photos by longtime Seattle music photographer Lance Mercer line the lobby walls at 9th & Thomas, capturing bands like Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, Sweetwater, Mad Season and Mother Love Bone, as they sing, sweat and seduce crowds in venues as tight as the Off Ramp and as loose as Lollapalooza. In the shots, fans are a forest of extended arms — some reaching out to catch stage-diving performers, some flipping the bird, some deployed as antennas to absorb the sound and fury.

“My favorite part is watching people come in to get coffee, get drawn in by one of the photos, then end up spending 20 to 30 minutes looking at the rest of them,” says Scott Redman, the Seattle native who owns the 12-story building with his father and lives on the top floor. The grunge exhibit, which is permanent, was his idea. It serves both his nostalgia and his overall goal for 9th & Thomas: “How can we leverage building space in the name of art?”

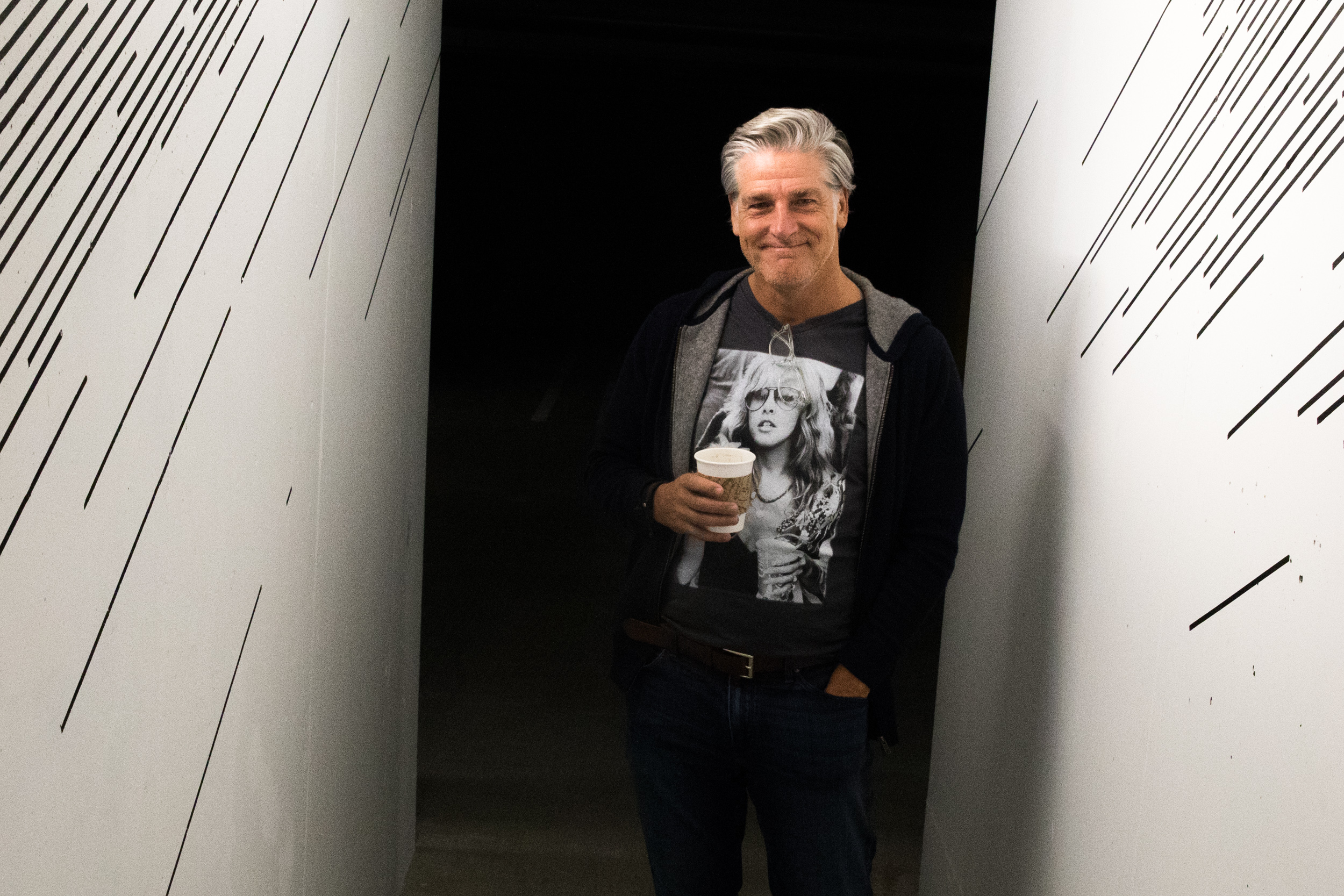

While perhaps not an established figure in the art scene, Redman, 54, knows a lot about building. Seventy-five years ago, his grandfather, John Sellen, started Sellen Construction Co., where Redman is now CEO. “It was originally located on this same property,” Redman says, “in a one-story brick building.” Now the largest locally owned general contractor in the Pacific Northwest, Sellen’s offices are just across the alley. This new building, designed by Seattle architect Tom Kundig, serves as both a family asset and a way to support artists. It’s also a gathering space. “We wanted to give back to the neighborhood we’ve been based in for so long,” Redman says.

Accordingly, the lobby is open to the public, via the main entrance and also by way of the first-floor restaurants — Elm Coffee Roasters, Jack’s BBQ and Thomas Street Warehouse. While it’s common for SLU buildings to incorporate restaurants, “No one else is creating a living room in the lobby,” Redman says. “We wanted to take an example from the hotel industry, and give people reasons to hang out here.”

Enticements include comfortable couches, soft rugs, open Wi-Fi, a long work table and a huge rectilinear chandelier, designed by Kundig, which sways as if dancing to the lobby soundtrack, an ever-morphing (and not grunge-focused) playlist curated by DJ John Richards of KEXP. (Sellen also built the KEXP headquarters at Seattle Center.) The coffee tables are stacked with thick architecture and design books, which Redman personally sourced from Seattle’s Peter Miller Books. All in all, “it’s a cool little ecosystem,” Redman says.

On a recent weekend, a group of middle-aged women sits in the lobby, heads down, writing in ruled notebooks. “That’s a writing group that’s started coming here every Saturday,” Redman says. “They write for a long time. It’s so great.” Another visitor leafs through several design books while sipping coffee. Others drift over to the photos and linger, then peer closer.

“This was part of my growing up,” Redman says of the rock photography. “I was a huge Pearl Jam fan. I loved going to the smaller venues — RKCNDY, Showbox, Crocodile, DV8.” He says he first encountered Mercer’s work at KEXP, and knew he wanted it for the lobby of his new building.

Born and raised in Seattle, Mercer has been shooting live music since the 1980s, starting with punk shows on the Ave. He says the 9th & Thomas connection came as a surprise. “I had a show of about 50 photos at KEXP,” he explains. “But I was actually in the hospital when Scott emailed me.” (Diagnosed with non-Hodgkins lymphoma in 2014, Mercer is managing the disease, and says it’s “totally beatable.”) “He told me he was interested in the prints, and I said, ‘Which one?’ and he said, ‘All of them.’”

Mercer thought Redman was joking. “As a self-employed artist, let me tell you, this never happens,” he says.

Redman ended up looking through Mercer’s immense archive and selecting nearly 100 images in total. “It’s the largest amount of work I’ve ever shown,” says Mercer. “It’s the closest thing to a retrospective I could have.” And there was another benefit: He says given his health issues, he was relieved to be able to dig deep into his collection — to focus on work and “dive into something other than sickness.”

During that process, Mercer says, “I realized Scott was getting all these other artists in the building. And these aren’t super established people. For some, this was their first commission.”

With the exception of Shepard Fairey, whose eight-story-tall banner graces the east side of the building, most of the other artists featured in the building are muralists Redman encountered when touring the SoDo Track mural corridor a year before its completion. He loved the idea and worked with 4Culture to commission several of the artists already traveling to Seattle to create additional murals for his building. “This way they’d have more places to paint, and they get paid twice,” Redman says.

The diverse murals — graphic, figurative, text-heavy, swirly — splash across the public parking garage below the building. “This is our underground gallery,” Redman says, as he walks through the parking levels and reels off the names of artists, from Broken Fingaz in Haifa to Aramis O. Hamer in Seattle. Clearly thrilled by the artwork covering the concrete, he plans to use the space for special events. As with the grunge exhibit, his intention is not to buy art and keep it to himself, but to share it with the public. He also wants to promote the artists at 9th & Thomas, and has peppered the lobby coffee tables with coasters featuring their art and Instagram handles.

“We’re trying to set a bit of an example, and show how you can support art,” Redman says. He notes that his plan for the last bit of open space in the building — a large-windowed first-floor corner — is to host pop-up galleries, including one curated by Gross contemporary art magazine.

Mercer is well aware of the dissonance between the scrappy grunge era and the tech wave that has brought tremendous growth to the city and pushed many artists out of studio and rehearsal spaces. He had to move his own studio from Belltown to Georgetown. But, he says of 9th & Thomas, “I never thought the space was too bougie or anything. It’s not sterile.” He pauses to clarify his thoughts. “Scott’s a Seattleite and he’s doing this in a very Seattle way,” he says. “There’s an authenticity.” Most important, Mercer thinks Redman’s project could influence other Seattle builders and people with deep pockets.

“I wish more people would use their money to do this … we need it, if Seattle wants to stay an artistic city,” Mercer says. “I get frustrated when people talk about Seattle’s arts community disappearing, but no one does anything. Scott is backing it up with action. I hope that’s a trend.”

Crosscut arts coverage is made possible with support from Shari D. Behnke.