The two property-tax levies combined would collect $1.95 per $1,000 of assessed valuation in 2020, costing the owner of a median-price home — $668,000 — about $1,300. The taxes would decrease each year, falling to approximately $1,080 for the median-price homeowner by 2022. Qualifying seniors and other dependents could be exempt.

The McCleary v. State of Washington decision in 2012 concluded that the state wasn't meeting its constitutional duty to amply fund K-12 schools. The lawsuit also raised issues with property-rich cities' increasing reliance on local levies, which has resulted in significant inequities for relatively poor districts.

The Washington Supreme Court ruled in June 2018 that the state Legislature had met its court-ordered deadline for fully funding programs of basic education, in part by imposing a statewide property tax levy for education. But taxpayer money doesn’t necessarily stay within one’s city; it is allocated across Washington’s nearly 300 public school districts. And Seattle Public Schools representatives say the district isn’t receiving enough state funding to accommodate its student population.

The state, for instance, pays for only nine of Seattle Public Schools’ 63 school nurses, who serve approximately 53,000 students, and a $72 million disparity exists between state funding and what the district spends to assist 7,000 students who need special-education services. Money raised by the Educational Programs and Operations Levy could help close those holes.

“We're very grateful and we recognize the progress that our Legislature has made, but there are still gaps that remain and that's where our money is going,” said JoLynn Berge, chief financial officer of Seattle Public Schools, during a press conference at Northgate Elementary on Jan. 24.

As statewide education funding has increased, the maximum amount Seattle and other districts can raise in local levies has diminished. Under current law, the district would be able to collect only about half of the $815 million over three years that makes up the operation part of its request to voters. But state Sen. Lisa Wellman, D-Mercer Island, introduced a bill last week that would increase the amount of local levy money districts can obtain. Without that or similar legislation, Seattle Public Schools will receive only part of what it is asking voters to approve for operational purposes.

Berge emphasized that while state lawmakers could decide during the 2019 legislative session to augment the funding the district receives from the state, the district's current request is based on what it thinks is needed. The district, in effect, hopes voters will approve its levy request to provide a safety net in case the state doesn't provide more. Otherwise, Seattle Public Schools could go without critical funding until the next budget year, in 2021.

If the district procures both additional state funding and more local levy dollars this year, Berge said that the extra money would be budgeted toward enriching arts curricula, hiring more librarians and adding more mental health services for students. But as it stands now, the district’s special-education programs are particularly vulnerable, with a pressing need for additional support staff.

“I think that there is general agreement that something will happen for special [education]; we don’t know exactly that will look like,” Berge said. “I think that over the last few months there’s been increasing support for recognizing that levies were taken down too low in the whole new McCleary funding.”

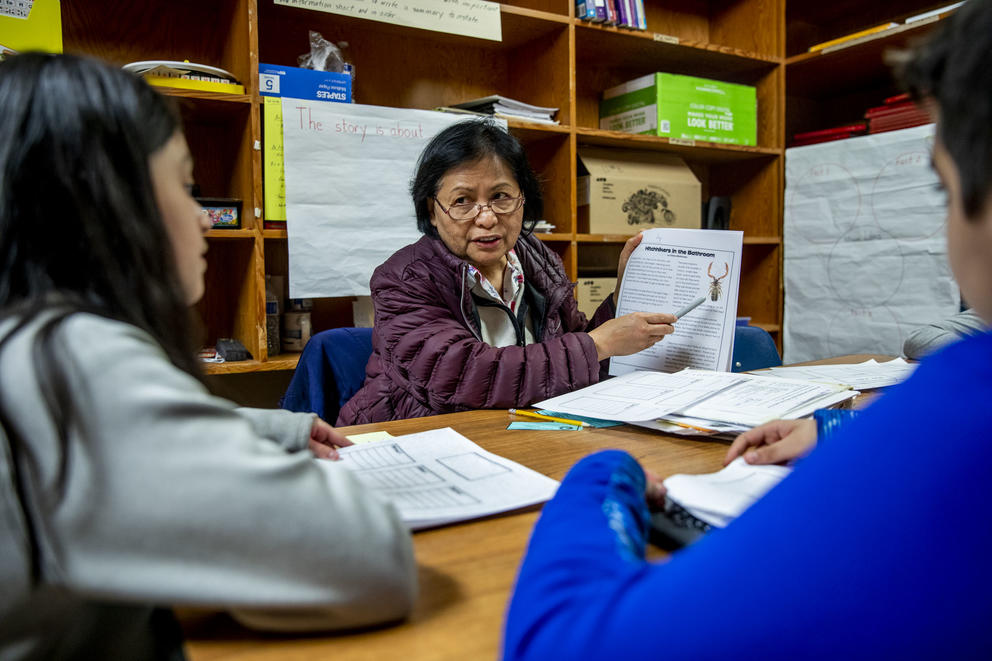

Teacher Marilyn Peterson instructs three students in a book closet at Northgate Elementary School on Jan. 31, 2018. This book closet doubles as a classroom because of the lack of space in the school. Expiring tax levies, if renewed, could raise $2.2 billion for Seattle Public Schools. The levies are on the ballot for a Feb. 12 special election. Northgate is a 60-year-old building that would benefit from the money for new facilities. (Photo by Dorothy Edwards/Crosscut)

Seattle Public Schools Supt. Denise Juneau added that her district is not the only one to experience funding shortfalls from the McCleary decision. Tacoma Public Schools recently eliminated a $23.4 million budget deficit by cutting 42 central office and support staff positions — about 14 percent of the district's administrative workforce.

Back in Seattle, schools like Northgate Elementary are in desperate need of capital for new facilities that are not included in Seattle Public Schools’ operations budget. Such needs would be supported by the passage of Proposition 2.

The 60-year-old school building and its six portables lack sufficient heating systems, making space heaters essential. Frigid air permeates the building’s hallways, compelling students and staff to wear coats as they pass through. Space is so limited that a makeshift office and classroom — at the edge of the hallway and in a book closet, respectively — have become necessary.

“We need a building that is as warm as our community is," said Principal Dedy Fauntleroy. “Our school is a neighborhood school and our neighborhood kids deserve it. We deserve our basic needs to be taken care of.”

Seattle residents have largely voted in favor of education tax levies for several decades. But McCleary reforms were supposed to diminish the use of local levies, and critics of the renewal efforts point to state mandates that municipalities can’t use them to fund basic education programs, further complicating the issue.

The Seattle Times editorial board has urged a no vote on Proposition 1, the operational levy. It argued that the size of the district's request is an attempt to pressure the Legislature into allowing larger local levies, potentially undoing the McCleary commitment to equitable funding across the state.

The statement opposing Proposition 2 in the King County voter’s pamphlet also raises concerns about how capital funding is allocated across the Seattle School District, and whether school enrollment is racially imbalanced as a result. Given Seattle's high housing costs, critics also have raised questions about how the levies might affect homeowners and renters.

But issues like housing affordability and the success — or lack thereof — of McCleary reforms exist separately from implementation of the levies, says Melissa Pailthorp, president of the pro-levy organization Schools First.

“The rates of the levies actually drop over time,” Pailthorp said. “I think we're all feeling property tax fatigue, but these levies aren't necessarily making them worse. It's absolutely understandable that the community is confused because education funding in our state is very complex and hard to track.”

She emphasizes that the levies aren’t just to raise funding for future projects; they are imperative for keeping what Seattle Public Schools already has in place.

“If we want families to move to Seattle, we have to have strong schools,” Pailthorp said. “To have strong schools, we need to have funding.”