A remarkably intimate portrait of prison life, the newly republished book from University of Washington Press provides an occasion to consider the particular path that led to mass incarceration in Washington state. Concrete Mama contains both profiles — cleanly written sketches of prisoners, a visitor and a prison guard — and sometimes-breathtaking black-and-white photographs depicting the idle, violent and socially complex world inside the Walla Walla prison during the late '70s.

Concrete Mama was first published in 1981; it won a Washington State Book Award the following year. But after selling well in the '80s, the book all but disappeared from libraries and bookstores.

Photographer Ethan Hoffman and writer John McCoy, then both cub reporters beginning their careers in Walla Walla, spent four months inside the Washington State Penitentiary in 1978. It was a time of significant transformation in the U.S. prison system. The previous two decades saw prison rebellions, fueled by decrepit conditions and the energy of the Black Power and Civil Rights movements, take hold across the country. Local governments responded by cracking down on prison organizing and pursuing a “more rigid, modular, and punitive strategy” for running prisons, writes Berger in the introduction to the new edition.

The Walla Walla prison, notorious then for overcrowding, rampant drug use, racial strife and harrowing violence, was no exception.

In 1980, U.S. District Court Judge Jack Tanner, responding to a class action suit brought against the state by more than a dozen prisoners, declared conditions at the prison unconstitutional. “The totality of conditions at Walla Walla is cruel and unusual punishment beyond any reasonable doubt,” wrote Tanner, in May of that year.

A striking photograph, midway through Concrete Mama, is just one of many examples of physical and mental degradation documented in the book. The photo shows a man, stoic but pained, peering downward and gripping the back of his neck. Just above the horizon line of the photograph is the gruesome remainder of his ear, the cartilage shredded away by the clenched teeth of an angry fellow prisoner.

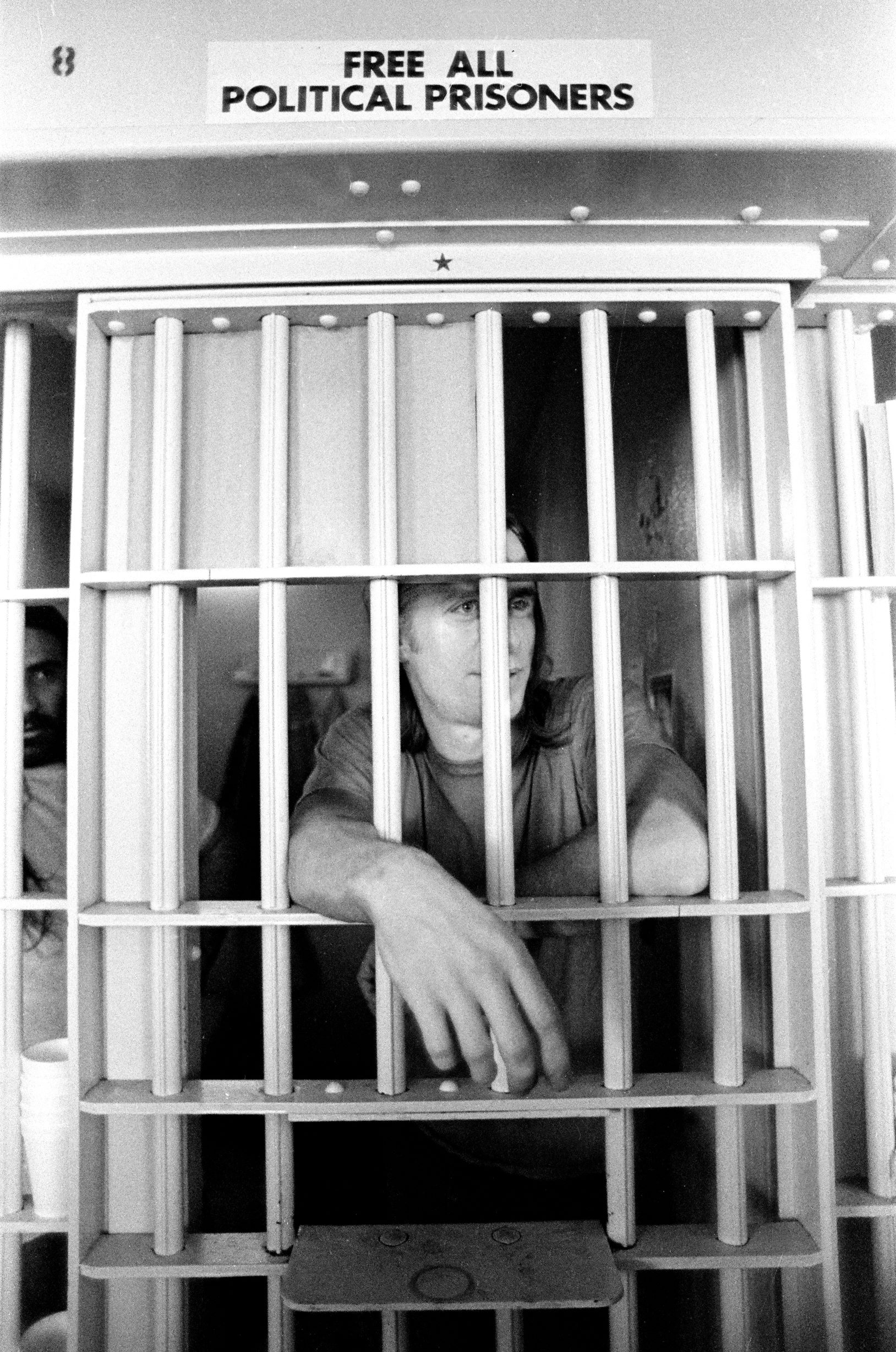

Most of the prison population shares cramped 10-by-12-foot, four-man cells with two bunk beds, a sink and lid-less steel toilet. The cell’s owner chooses his cellmates. (Photo by Ethan Hoffman, taken at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla, Washington, 1978-1979. Courtesy of the Washington Prison History Project and UW Bothell Digital Collections.)

Not much attention has been paid to our state’s role in the uniquely American story of mass incarceration, Berger says. That’s why he, with the help of Ed Mead, a former prisoner at Walla Walla who donated his papers to University of Washington Bothell and is profiled in Concrete Mama, recently launched the Washington Prison History Project, a growing online archive that coincides with the book’s re-publication.

Crosscut contacted Berger by phone recently to discuss the book, the history of mass incarceration in Washington state, and how conditions have and haven’t changed at Walla Walla since Concrete Mama's original publication. The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You got the idea to revisit this book after Ed Mead donated his papers to the University of Washington. What can you tell me about him?

Ed Mead spent almost 20 years in prison for his involvement with the George Jackson Brigade, an anti-capitalist guerilla group. He served as an activist inside the prison as well, and so his papers were not just items pertaining to his case, but a look at the organizing and collective action taking place in the prison at the time. One of the most fascinating things he was involved in was a group called Men Against Sexism, which was an organization at the Washington State Penitentiary by and for gay, queer, trans and effeminate prisoners. It was meant essentially to provide protection from rape and sexual violence. This was an unprecedented organization to have inside a prison, and Concrete Mama is really the only book I’m aware of that came out at the time that talked about [Ed Mead's] organizing inside the prison.

Why is Concrete Mama relevant today?

As mass incarceration becomes a controversial issue, and one that people are trying to address, there is a lot of talk about what has and hasn’t worked in the past. Concrete Mama shows one example of a prison reform experiment that was not really committed to and ultimately failed. I think revisiting it can show us some of what it might take to actually reform prisons for the better.

The reform experiment at Walla Walla was intended to make the prison run more like they do in Scandinavia. What did that look like and why didn't it succeed?

The Scandinavian model allowed for prisoner self-governance. There was less censorship of the types of materials that prisoners could receive. Prisoners could wear what they wanted, and they were given more access to the outside world.

That was the vision for Washington state under a man named William Conte, who was the director of institutions at the time. But the vision was not shared by many other people within the prison system; certainly not by most of the guards.

This also came at a time when the demographics of incarceration were changing. African Americans, Native Americans, and Latinos were being incarcerated at tremendously disproportionate rates. Now that’s a story that feels very familiar to us. But in the 1960s and 1970s, that really was the turning point. The exact moment when Conte is trying to unroll this experiment, you have a largely urban prison population being guarded and often brutalized by a largely white rural population. And that became further justification for the kind of hostility with which many people in the prison system greeted this attempt at change.

How are conditions at Walla Walla today?

While I was writing the introduction, there was a major hunger strike at the prison. There are ongoing lawsuits about the treatment of people with mental health problems. That gives you some idea.

It was really important for me to actually interview people who have been there since the book (first) came out. I spoke with two men, one of whom, Art Longworth, was there for several years (and is now incarcerated elsewhere), and another, Darrell Cook, who remains incarcerated in Walla Walla. Both painted very grim pictures of what the prison is like.

Art talked about a group called the Cross Revenge Squad, a mercenary subset of guards that took it upon themselves to avenge the killing of [murdered Sgt. William Cross] in 1979. They responded by brutalizing prisoners, which lasted for several years and preceded a more punitive turn in how the prison was run.

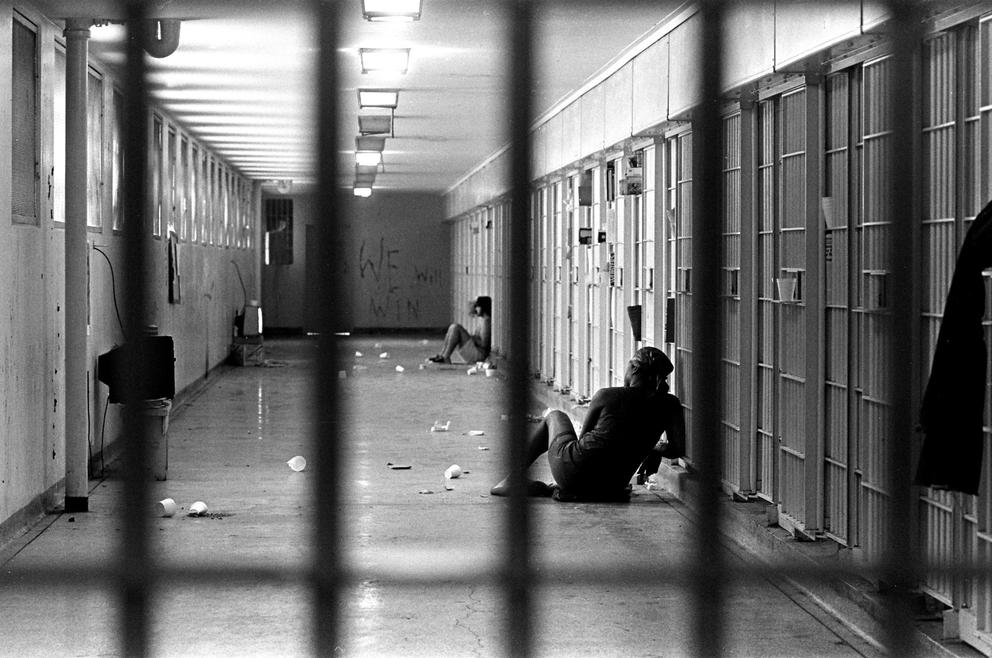

The segregation unit’s B-tier, the most hostile place in the penitentiary, houses what administrators considered the most violent and dangerous prisoners, including many of the prison’s organizers. “We Will Win” is scrawled on the back wall, a reminder of a recent disturbance. (Photo by Ethan Hoffman, taken at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla, Washington, 1978-1979. Courtesy of the Washington Prison History Project and UW Bothell Digital Collections.)

On top of the physical violence, there was an administrative reconfiguration of the prison intended to maximize isolation, through long-term solitary confinement. In Washington, they do that through something called intensive management units, or IMUs, and hold people in a cell for 22 to 24 hours a day. The prisoner’s only time outside is one hour alone, in a narrow outdoor hallway, like what a bad kennel does when they let dogs outside.

As for Cook, he described what he calls “grin-and-bear-it slavery,” without the forced labor. He talked about how people in the prison are provided with very little programming, with very little opportunity to do anything resembling a meaningful human experience.

Both the original version and the new edition show that most people in prison have very little to do. There’s not even slave labor, for far too many people.

In the introduction, you sketch some of the policies that contributed to mass incarceration in Washington state. How in 1993, for example, we were the first state in the nation to pass a three strikes law. What else helped pave the road to mass incarceration here?

Washington passed something called the Sentencing Reform Act, which went into effect in 1984. It eradicates parole, making it a lot harder for people to get out of prison. That coincides with a lengthening of sentences, where you get more and more people serving longer sentences with fewer opportunities for release.

The Sentencing Reform Act, as it was initially implemented, was designed to focus on people convicted of violent offenses. So Washington’s prison population in the mid-’80s actually drops slightly, when around the country it’s rising. But then Washington did what states do when the prison population drops: contract out its empty beds to the federal government. The state ends up receiving several hundred federal prisoners, mostly young Black men from Washington, D.C., who are incarcerated from the war on drugs.

Meanwhile, this tough-on-crime ethos had infected the body politic, and politicians here, as everywhere, were trying to outdo themselves by getting tougher and tougher on crime. The Sentencing Reform Act gets amended every year, becoming tougher and tougher. After a couple of years, Washington can no longer have prisoners from D.C. because there are all these new prisoners here who need to be incarcerated.

How are conditions at other medium and maximum security prisons in the state?

I think a lot of people prefer [the Washington State Reformatory in] Monroe because it’s a little more relaxed, not as punitive as Walla Walla. Incarceration has a very defined geography. Most prisons are located in rural areas, and most prisoners are from urban areas. The majority of people who are incarcerated here are from Western Washington, so being at Monroe at least increases the likelihood that you might get visits or might be able to benefit from the largesse of the Seattle area, in terms of programming that’s available. Plus, there’s a lot more opportunities for education at Monroe than there is at Walla Walla or Airway Heights or Clallam Bay. I don't think anyone looks at any prison with envy, but it seems like Monroe is the most desirous of the medium and maximum security prisons.

Much of the story you tell in your introduction is horrifyingly grim, particularly the details about sexual violence. Yet the journalists who put this book together are careful to highlight the humanity that found a way to express itself in the prison. Can you talk some about the tender relationships that emerge in prison?

Sexual violence in prison is something that is often referenced and sort of cruelly joked about in popular culture. The wider panorama of sex and sexuality and power in prison is not really well understood. Part of what is so helpful about the book is, yes, the brutal look it provides of the prevalence of sexual violence among prisoners, but also of the consensual, romantic relationships between people. A number of LGBTQ prisoners both then and since have written about finding affection and tenderness and support among other incarcerated people. It’s to the book’s credit that we see groups like Men Against Sexism — both for the political radicalism that people like Ed Mead imbued it with, but also for the social and romantic outlet that it provided for LGBTQ prisoners.

Kim, right, spends time with Leomy, his “inside lady” and a member of Men Against Sexism, a club popular with gay and transgender prisoners. (Photo by Ethan Hoffman, taken at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla, Washington, 1978-1979. Courtesy of the Washington Prison History Project and UW Bothell Digital Collections.)

Because the idea of the prisoner exists as this boogeyman for society, we often don’t take seriously the full selves of incarcerated people, which includes romantic as well as various other kinds of platonic affection and love that I think the book captures.

I think prison is this tremendous argument for how social human beings are. You can put people in the most miserable and isolating of conditions and they will try and find ways to exist with other people. I think we should be attentive to the way that people in prison form nurturing and positive and healthy relationships despite those structural barriers.

You write that Concrete Mama illustrates not the failure of prison reform, but the failure of prisons. What do you mean?

What a number of currently and formerly incarcerated people have told me is that many Washington state prison officials look at the book with an odd sense of pride. They seem to say, We gave prisoners a chance and they screwed it all up! That’s why we need these get-tough approaches!

I don't get that impression reading the book at all. I got the impression that when you lock people in a cage, tell them they are a terrible person, deny them meaningful experiences for being a human, then there’s no good that can come from that. I think the book shows that well — in the despair that people testified to, in the loneliness, and in the violence that some people commit and experience, both from other prisoners as well as from guards. But also in the beauty and joy and wonder that people create despite prison, and against prison, rather than as something that prison facilitated. I think the book is a really stirring indictment of prison itself.

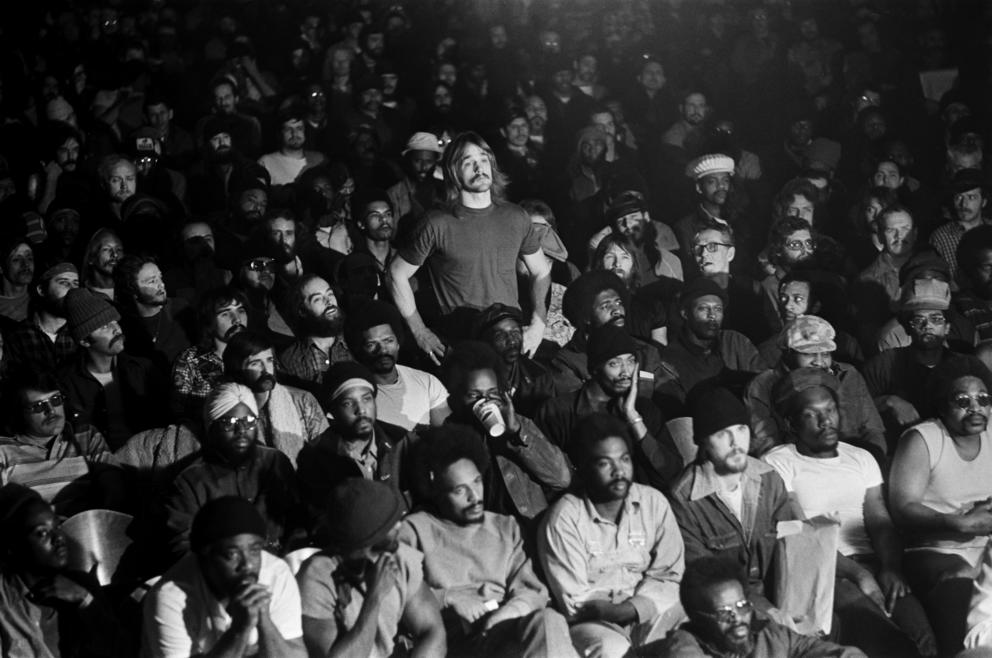

Warden Douglas Vinzant, a champion of prison reform during his brief tenure at Walla Walla, addresses prisoners who completed high school and community college programs at a graduation ceremony in the Big Yard. (Photo by Ethan Hoffman, taken at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla, Washington, 1978-1979. Courtesy of the Washington Prison History Project and UW Bothell Digital Collections.)

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.