Since then, a rotating cast of 17 lucky dogs has spent their days in Washington's 4,300-acre Pack Forest with nine handlers. Conservation Canines (CC) looks for dogs with tireless energy and a need for stimulation — traits that prevented them from finding homes, but which makes them ideal scent detectives. They are taught to approach scent detection as a game, where they are rewarded for learning how to track the scents of dozens of species' feces.

With their exceptional olfactory abilities, scent dogs are 19 times more efficient and 153 percent more accurate than humans at hunting down species-specific scat. Data gleaned by CC and its trainers gets funneled into worldwide research programs that study everything from identifying the range of endangered caribou to tracking Orca scat by boat.

The work is important: Scat samples provide significantly more data than hair snares, camera traps, and other animal-monitoring services. Photos, for instance, show only an animal's presence and movements. Scat can also reveal information about its diet and overall health. And by using non-invasive dog tracking to do this, scientists can explore human impacts on animal populations over large swaths of land with minimal interference.

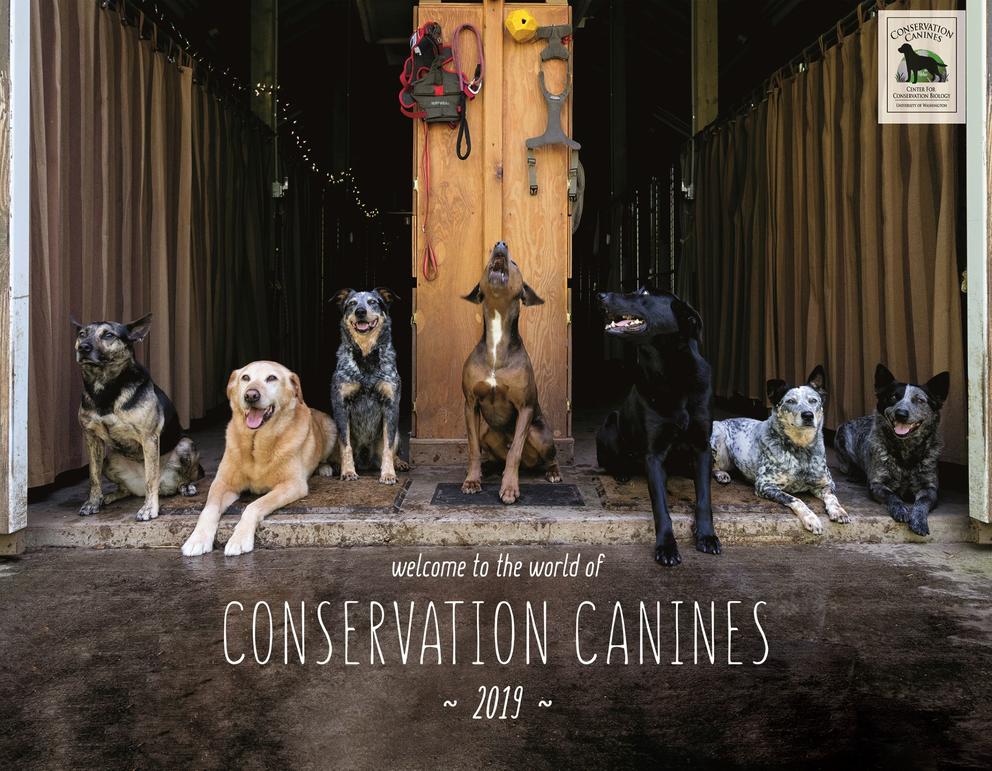

For the past four years, wildlife photographer Jaymi Heimbuch has shot and designed a CC calendar to raise funds for the nonprofit, and share exactly what it means to be a shelter-dog-turned-"Conservation K9" (CK9).

All photos credited to Jaymi Heimbuch.

The adventure begins

In 2014, Heimbuch was volunteering as a photographer for Hearts Speak, a foster dog nonprofit, when she came across CC. She thought connecting with the organization would be a way to explore wildlife photography while using her dog-focused skills in a charitable way.

Heimbuch fundraised all of her expenses to photograph each dog on location, produce the calendars, and ship them. She raised more than $5,600 through calendar proceeds that first year. In the next, she raised more than $10,000.

"Even though it isn't even a huge money-raiser, especially not by UW standards, it's something that people really look forward to every year," she says.

In 2018, CC began paying Heimbuch for her calendar work. The success of the project has helped Heimbuch transition from a career in web journalism to animal and conservation photography full-time.

Getting the hang of tracking

Heimbuch focuses each Conservation Canines calendar on a theme. This year, Heimbuch wanted to tell the story of a dog's life, from the dog's point of view.

The training process is key to that story. Before dogs go out in the field, they must become adept at identifying scents, differentiating between them and signaling to their handlers when they've solved a case.

In the photo above, Dio engages in one of the early-stage training games: Handlers screw a jar filled with scat to one of the many holes drilled into this board. On the other side, Dio is tasked with sniffing the holes until he discovers which one is attached to the scat jar.

As dogs improve, the game evolves. The jar-sniffing challenge moves from home to the woods to scat planted in the ground and, eventually, naturally deposited scat.

"They're basically expanding the game to a real-world situation," Heimbuch says.

The challenge of shooting CK9s

Heimbuch specializes in shooting North American wildlife like bears, coyotes and birds. While CK9s won't run away like wild animals, she acknowledges they are wild in their own ways, and untrained for anything other than tracking work.

"[Handlers] are so focused on having them be working dogs. They don't need them to perfectly heel," Heimbuch says. "But they have the body language of domestic dogs, and it's a little like portrait photography in that I can still control the situation."

Getting to know the dogs and anticipate what they'll do has been essential to capturing them in action, she says.

"They have their own way of looking at the world and they usually have a lot of energy and they usually want to be doing something," she says. Depending on that point of view — whether they mind her presence, or their personal space bubbles, or how easily they get frustrated — affects the way she interacts with them to get the shot.

From shelter reject to calendar star

There's a lot Heimbuch loves about producing the calendar, but what it represents means the most.

"I feel like the best part about this entire project is that it strengthens support of this type of work for dogs and the idea that these dogs go from being these last-chance shelter dogs that nobody wants or can handle as pet, to becoming these incredible co-workers and co-stars in the conservation world," she says. "And to be able to bring people's eyes to that and get them interest in that through imagery means the world to me."

The Center for Conservation Biology's Conservation Canine Program works hard to provide effective noninvasive alternatives for monitoring human impacts on wildlife over large remote areas. Our highly dedicated teams love what they do and set high standards for others to follow.

A job well done

Heimbuch says this photo epitomizes the handler-dog relationship in the field: in this case, how dog and handler can switch quickly between hyperfocused work and moments of silliness and exuberance after successful scat identification.

"For the dogs, it's not really a job — it's play for them," Heimbuch says. "To see a moment where they're just being happy and silly together, I remember every one of the dogs and humans does this because they love it."

Say cheese

To get the perfect shot, Heimbuch has to ensure she doesn't interfere with the dogs' training. Repetitive tasks — like the kinds often used in modeling — can confuse their training.

"If we're out in the field and we want to set up a shot of them sniffing, you have to know what that dog is willing to do before you get frustrated," she says. The dogs have limited patience for being asked to sniff along a route that doesn't have any scent, or discover scat that has already been discovered.

This old dog

CK9s never really retire — they simply take on another role.

When 14-year-old Chester retires, he'll likely get adopted by his handler and join four other "CK9 alumni" in assisting with education and outreach. Taking the dogs to schools helps get students interested in conservation field work.

But Chester has been an active tracker for a decade, and isn't quite ready to become an education ambassador, Heimbuch says.

"He's been a world-traveling dog and has every bit as much energy and stamina and joy and endurance of any of the younger dogs. He's just go, go, go," she says. "[Handlers] really watch how much they work him to make sure that he doesn't ever get overworked. They're thinking about his age a lot more than he's thinking about his age."