James thought he was a big shot, and Tinseltown big shots snorted cocaine and guzzled booze like there was no tomorrow. James wanted out of that vicious cycle, so in 1994, he and his wife, JoAnn, decamped for Lake Stevens, Washington, where they planned to stay with some fellow California expats until they found their own footing.

That would take some time.

James didn't exactly kick drugs right away. His adult son, Guy McNally, came to visit and the two split a bag of mushrooms and tripped out to the peaceful, easy sounds of The Eagles. It was then that James’ life in the fast lane came to an abrupt halt by virtue of a psychedelic apparition.

"He saw God telling him to quit doing dope, and that day he quit everything," recalls McNally, a barrel of a man who bears more than a passing resemblance to the musician Tom Waits.

"He started crying and people thought he'd gone crazy," adds JoAnn.

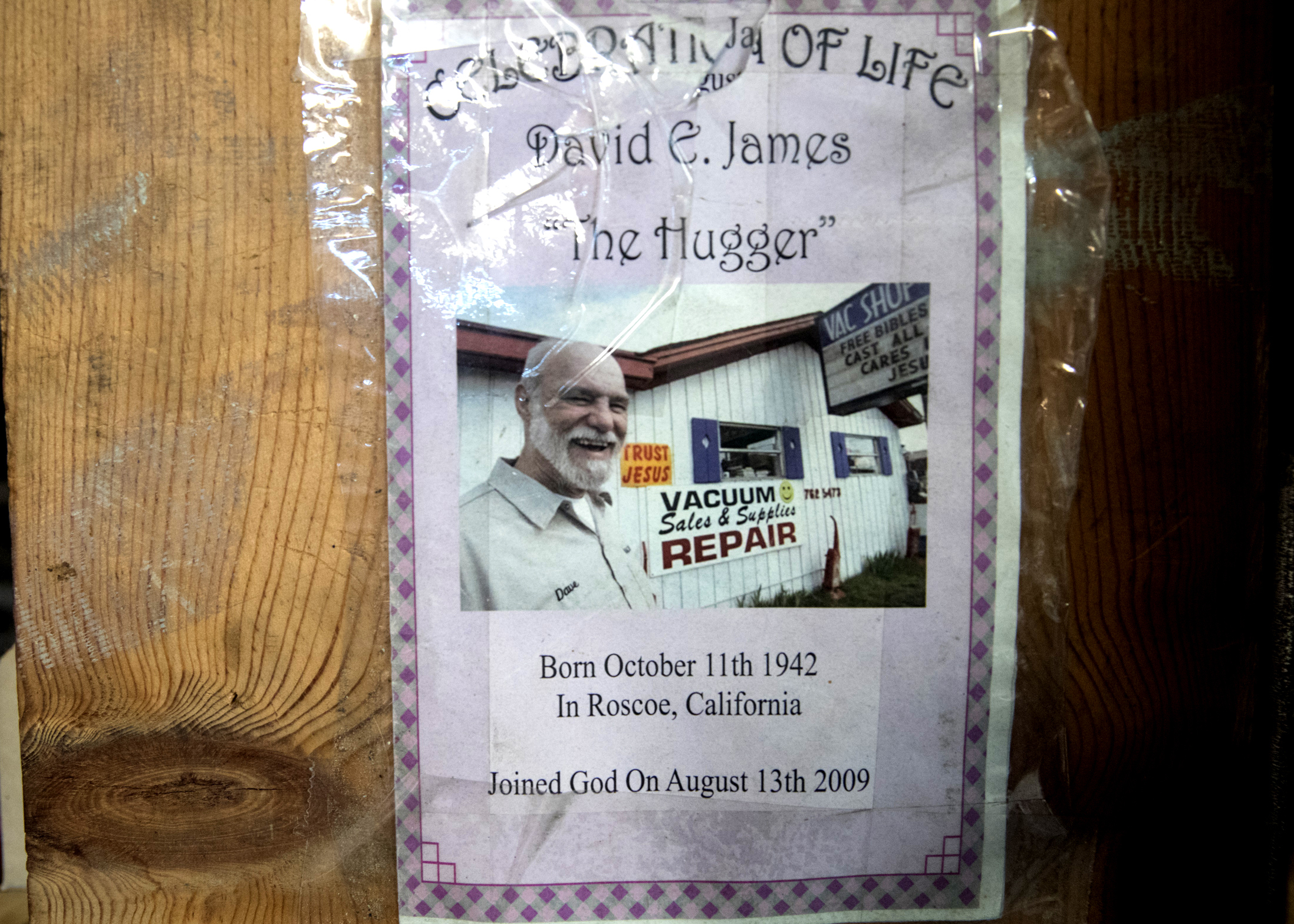

Newly sober and religious, James also wanted out of the vacuum-cleaner business. But, as his wife puts it, "the Lord had other ideas." James nearly landed several sales jobs in other industries, but fell shy of getting hired. Accepting that his life's vocation would be to fix and sell machines that help people tidy up their own messes, he took a job at The Vac Shop on South Lucile Street (at 4th Avenue South) in Georgetown, purchasing the business in 1996.

James and wife JoAnn quickly set to turning what had been a nondescript business in an industrial backwater into a local curiosity. For one thing, the shop's service manager, Will Flannery, and some neighborhood artists began transforming old vacuum parts into robots, reindeer and other characters and positioning them outside the store.

Guy McNally takes stock of vacuums inside a large storage container adjacent to The Vac Shop in Seattle's Georgetown neighborhood, Nov. 16, 2018. "One man's trash is another man's treasure," says McNally. The store saves hundreds of vacuums that customers discard, then use them for hard-to-find parts when repairing other vacuums.

That the figurines — which give The Vac Shop a Pee-wee's Playhouse vibe — would often get stolen hardly served as a deterrent. To this day, artists often approach the Jameses in hopes of mining the old tubes and motors for sculptural ingenuity.

Then there was the matter of the shop's marquee. James, who died in 2009, was serious about repaying God for helping him clean up, so he set to stockpiling Scripture in hopes of spreading The Word. On his reader board was the perpetual "Free Bibles" advertisement, along with messages like "God loves you no matter what."

Was this a vacuum-repair shop, a "yart" gallery or a makeshift church, proselytizing in defiance of a very secular city? All three, really, and so much more.

"It's not just like a regular business," says Jan Johnson, the live-in owner of the International District's historic Panama Hotel. She first encountered the Jameses when the Capitol Hill shop that serviced her vintage vacuum cleaners —"They're better than the new ones," Johnson insists — closed.

"I'd seen that place on Fourth Avenue and absolutely adored the way they decorated it," says Johnson, whose commitment to seasoned machinery extends to her 1939 Ford. "So I visited and they were incredible. JoAnn's a dying breed. She's very powerful. She roars. Even if you're not religious, when she says, 'God bless you,' you know you're gonna have a great day."

The septuagenarian can be stout as well. Wielding her walker on Election Day, JoAnn greeted a transient couple in the Vac Shop's cramped showroom. While his female companion appeared eager to take a swig out of a nearly empty beer growler hanging from her left index finger, a young man explained that he was there to reclaim a bicycle he'd parked among the vacuums.

Not so fast, said JoAnn, who first had to check with McNally to make sure the man's story passed muster. It did, so he was permitted to wheel his bike out of the shop, which often serves as a way station for the neighborhood's more downtrodden denizens, some of whom occupy camper communities near a sawdust yard to the south and Georgetown Brewing to the north.

Helping the needy was something James had considered part of his unlikely lay ministry. And it remains part of what it takes to do business on Fourth Avenue, which seems far removed from the bustle of nearby Airport Way South's hip restaurants and bars.

"Most of the stuff near Spokane [Street] has cleaned up, but [homelessness] is still pretty prevalent down here," says Adam Estner, who manages LECT's Soup Stop on Denver Avenue South. The tiny takeout shack is owned and operated by the Life Enhancement Charitable Trust (hence, the name LECT), a charity that assists recovering addicts with health-, vision- and dental-care expenses. McNally regularly swings by the Soup Stop to pick up lunch for himself and his mother; fittingly, Estner calls him "a great guy."

Shortly after the Jameses assumed ownership of the Vac Shop, they gave away as many as 20,000 free Bibles per year. Now that figure has dwindled to "maybe 10 or 20 a week," says JoAnn. She chalks this up to people's ability to access Scripture via "iPods and ePods and all those other pods," concluding, "It's not a world where you need books, I guess."

It's also not a world that needs independent vacuum shops, evidently. When asked who their competition is, McNally replies, "Nobody. There have been five stores that have closed around us within the last year or two."

Yet JoAnn reveals that the Vac Shop may join this list of casualties. She says she's considering closing up shop at the end of the year. If that happens, McNally says he'll reopen the shop in a vacant storefront nearby, but JoAnn dismisses this notion by explaining that her son is "talking through his butt."

Echoing a common refrain among brick-and-mortar retailers, JoAnn explains, "We'll sell something and people will come back and want a refund because they'll find it on the internet for cheaper. But Amazon won't service them."

Circling back to her own shop's plight, she warns, "The little mamas and papas, I don't know if you'll have 'em."