But for Black authors in the mid-1990s, the publishing landscape felt oppressively narrow. With the popularity of “urban lit” booming, publishers had a limited vision of what African-American stories were marketable, and that vision did not speak at all to Baszile’s life experience or the stories she wanted to tell that showed a more complex and nuanced perspective.

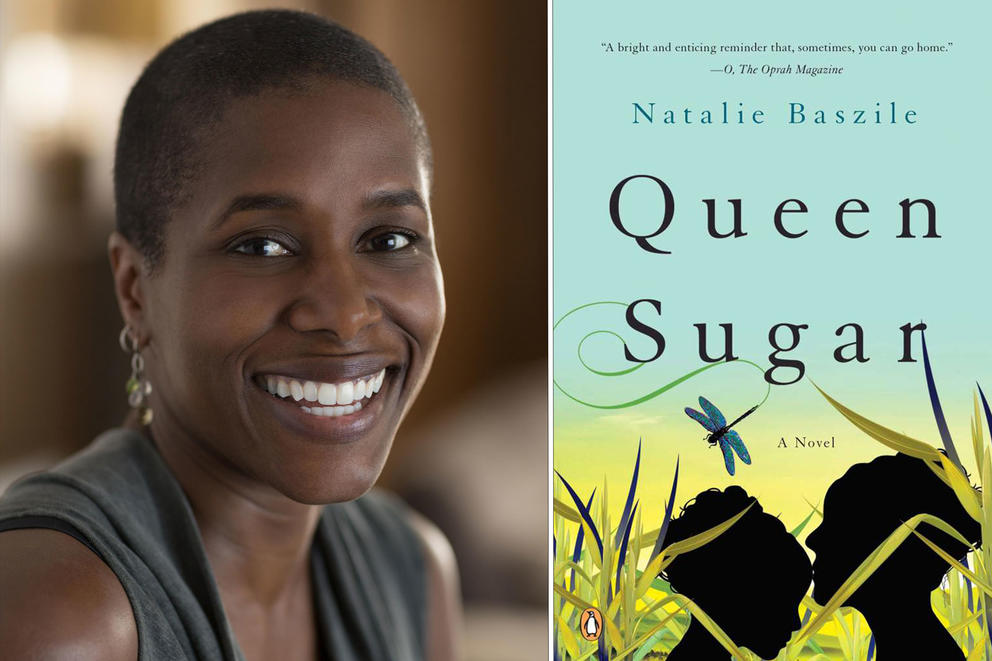

Yet, after 12 years of work, Baszile’s first novel, Queen Sugar, was finally published in 2014. Set in the richly textured landscape of south Louisiana, the book follows the Bordelon family and, in particular, the California-raised outsider, Charley, as she navigates inheriting a sugar cane farm.

As much as any character, the landscape, culture, traditions and people of south Louisiana are the heart of the book. Now an Ava DuVernay created and produced TV series with devoted fans on Oprah’s OWN network, Queen Sugar has found a passionate, new audience. While the TV series takes some significant departures from the book, at their core, both the novel and show are about family and the complex ways families uplift, disappoint, betray and love to create a legacy and community. We talked with Baszile by phone in San Francisco on writing and the importance of place.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

It took 12 years to write the book. Were there times when you questioned whether it was worth it?

I mean there were more moments of doubt. That doubt arose from everything from trying to figure out how to write and trying to learn the craft of fiction to moments of wondering if I was the right person to tell this story. Thinking at moments that it was too big, that I've bitten off more than I could chew. And then there was all of the rejection from agents. When I thought I was ready the first time to send the manuscript out, I got some lovely rejections. But they were still rejections. So, yeah, the whole process was riddled with doubt balanced out by moments of tremendous joy. And a feeling of triumph and a feeling that I was doing exactly what I should be doing.

The mistake that people make is assuming that writers just sit down at the desk and the words flow the very first time around. It's a process of grinding out that first draft and trying to feel your way through. Often not knowing how this story is going to unfold. What's going to happen to the characters. And it really is in many ways an act of perseverance and determination and just blind stubbornness and faith.

What has been the reaction of Louisiana folks to your book and how it depicts their communities?

People love the book. I mean they love the story because one thing that a lot of people in Louisiana used to tell me was they were frustrated with the way they were portrayed in books, movies, television, whatever. They never felt like they got a fair shake. And they were [appreciative] that I was interested in portraying them as they really are. Appreciative that I would take the time to actually get to know people and celebrate south Louisiana culture.

I had many, many people say they see their own family dynamic in the book. They have a brother or an uncle or a cousin like Ralph Angel. They have a Miss Honey or they have an Aunt Violet. That's one of the things that I wanted to do from the very beginning. I wanted the book to be an American story. Yes, it's about Black characters. But I wanted something in that story that resonates with lots of different people.

What was your experience in south Louisiana?

One of the things that I know for sure about Louisiana is that you can drive from Lafayette in the west to New Orleans in the east, and if you stay on the interstate you will never know that place. You will never experience Louisiana culture. You have to get off the interstate and you have to be in those small towns. You have to hopefully know people in those small towns. In order to make my story ring true, I had to get off the interstate.

I was fortunate enough to meet one guy in particular who at the time was a sugar cane farmer who really was my guide to the culture. He was incredibly generous with me and opened up his home and has introduced me to his family and introduced me to what it meant to live a certain kind of life in south Louisiana. It allowed me to inhabit that world in a way that I otherwise would not have been able to. I would end up planting sugar cane or I would end up harvesting sugar cane with some local farmers.

What’s the role of place in your book?

The early drafts are set in a fictitious version of the town that my dad grew up in. He is from a little town called Elton, Louisiana, that is near Lake Charles. As a child I didn't really grow up knowing much about Louisiana at all; I grew up in a suburb of Los Angeles. But when I did start to go with my dad on these road trips, I was struck by how different the landscape was from what I knew growing up. I grew up near the ocean and you know you could smell the sea air and you could hear the waves crashing and all of a sudden I was in this relatively landlocked part of Louisiana. In my grandmother's town, they grew crawfish and rice. It was the topography that was so striking. It was beautiful. But in a completely different way.

I also noticed that people had a different relationship to the land than I had experienced. People went digging for crawfish, or they went fishing, or I have a cousin whose name is Bozo, who had a fish camp and I never heard of a fish camp before. Years later when I picked up that version of the book that was set in crawfish and rice country and I set it down in sugar-cane country — which is another region of south Louisiana — again I was struck by how different the landscape was. It was visually stunning with the acres and acres and acres of sugar cane fields. One of the reasons why place factors so prominently in the novel, and why it is so interesting to me as a writer, is because I came to understand that my characters would have a different outlook on life based on their connection to their landscape.

Can you talk about the ways Black writers are making a difference in the publishing industry?

We're seeing much more range in the stories that are told as there are more and more young Black writers coming up. I think you're seeing a widening again. You're seeing a deepening of experience. You're starting to see a resurgence, another renaissance, of African-American/Black writers writing about this experience from a variety of points of view. And that I like. You're starting to see Black science fiction, speculative fiction and sci-fi that you never saw before. That's all encouraging to me because it means that you have Black writers out here telling a range of stories.