Seattle-based actor and filmmaker Lerman spent a decade transforming the patchwork of tales into Cyla’s Gift, a colorful and poignant hour-long solo piece.

“I’m the final branch of a family tree where every other branch has been cut off,” Lerman states in the show, which plays at Taproot Theatre through October 13.

A wiry, youthful performer and filmmaker, Lerman is an ingratiating presence as she energetically traces family history by transforming into her grandmother as a child, a woman, an elder. She also plays herself at various ages, and other relatives keenly impacted by the adventures Cyla embarked on in the 1940s and its later psychological repercussions on her own generation.

“My grandmother was an incredible storyteller,” Lerman says. “After she died in 2008 I started to write about her. Then I’d put the project on the shelf, and later it would call out to me to bring it down and work on it.”

Lerman was acutely aware that at this point in history, the generation of Holocaust survivors from the World War II era is dying away. And as their children head into old age, it is increasingly up to the grandchildren to keep alive the stories of those who witnessed and survived Adolph Hitler and his Nazi regime’s systematic annihilation of six million European Jews, along with many homosexuals, gypsies and leftists.

“For me, it’s been a responsibility to share these stories,” says Lerman, a veteran performer who has acted with Seattle Shakespeare Company and Book-It Repertory Theatre, and recently directed the 2018 indie film, Amaajii.

“As each generation gets more removed from the Holocaust, the memories get fainter and fainter. It’s like we have all these ghosts sitting on our shoulders.”

But she accentuates that Cyla’s memories, emerging out of one another “like Russian nesting dolls” in the play were more action-packed and intrepid than grim. “The show is not an exercise in suffering. People have been a little relieved that it’s sometimes very funny. Jews have a long history of using humor to deal with pain.”

The production zig-zags across time and place, as it follows the trajectory of a fascinating life. “Cyla’s father, my great-grandfather, owned a mill in Maniewicze, a village in Ukraine, and she’d talk about her idyllic childhood there, playing in the woods and studying,” said Lerman. In 1939, when the Soviet Russians occupied the town, Cyla joined a Communist youth group. Then two years later, the Russians departed as the Germany army arrived, and during the Nazi occupation, a reign of terror began.

Fearing for her life because of her Communist affiliations (she didn’t yet know being Jewish was more of a target), the 17-year-old Cyla grabbed her younger brother Yolik and they fled into the nearby woods. She survived by her wits, and their adventures included sleeping in forests, scrambling for food, riding the rails in boxcars, and near brushes with death as they outwitted border officials and soldiers. As in an action movie, “she was always one step ahead of the bad guys. She and Yolik were sneaking across borders,” recounts Lerman, “even when they were closed.”

Through a series of surprising events, Cyla and Yolik wound up thousands of miles from home in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. And after the Allies liberated Europe in 1944, they were consigned to the Föhrenwald refugee camp in Germany (where Yolik died of tuberculosis). In the camp Cyla met and married a Jewish widower (who had lost his wife and children to the Nazis) and gave birth to a son whom she vowed would “never go hungry.” But it wasn’t until they’d spent several years at the camp that a distant cousin sponsored their migration to America in 1949. The family settled in Wisconsin where Cyla’s second child, Samara Lerman’s mother Golden, grew up.

At one point Cyla learned her parents, her siblings and all the Jews still residing in her hometown had been killed by the Nazis. These are some of the “ghosts” that lingered throughout her life and still haunt her granddaughter.

How to convey a saga that covers so much geographical territory, so much feisty survival and so much grief and loss? It hasn’t been easy, acknowledges Lerman.

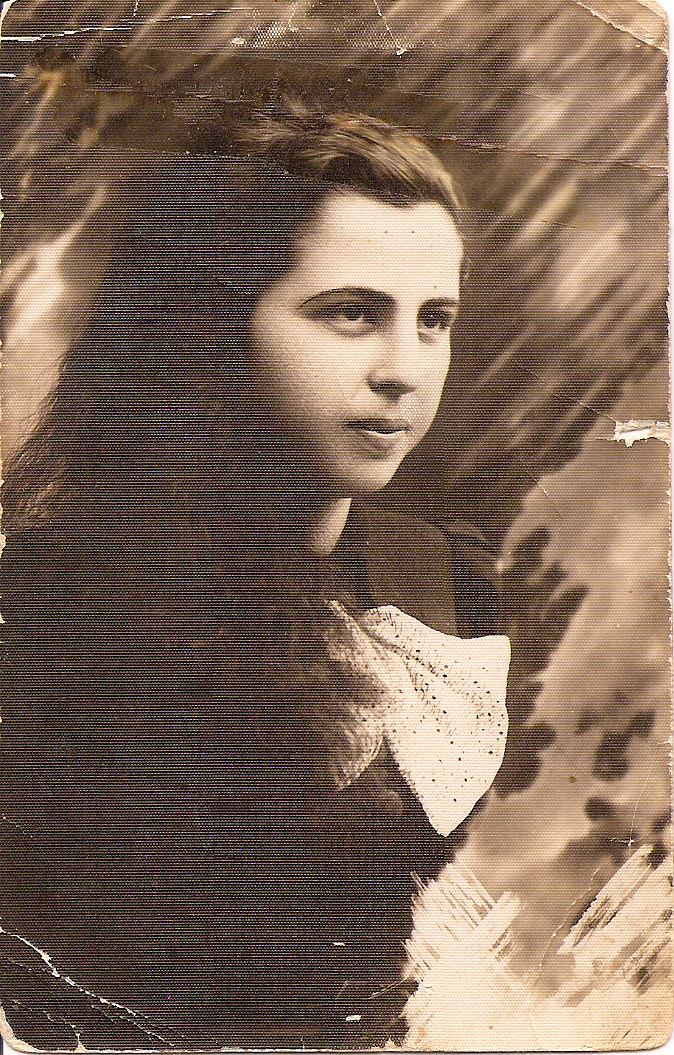

“Cyla was interviewed by the Wisconsin Historical Society, so I had 80 pages from that of transcript to work with. I also had to do a lot of my own research and guesswork.” She and Kelly Kitchens, the show’s director, also brought in gifted theater designers to give Cyla’s Gift a unique sound and look. The impressionistic set incorporates Lerman’s family photos and evocative projections based on original charcoal drawings. And there’s an effectively atmospheric sound design.

Certainly, countless feature and documentary films, plays, memoirs and novels have conveyed the personal experiences of Holocaust survivors. There are now Holocaust memorials and educational centers in more than two dozen states, including the Holocaust Center for Humanity in Seattle. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC has attracted some 43 million visitors from around the world — approximately 90 percent of them non-Jews.

But there are still Holocaust deniers in the U.S. and elsewhere who loudly insist that Jews and others were not systematically exterminated by Nazi Germany, sometimes in collusion with other European nations. According to the Washington Post, during the 2017 presidential election in France, “34 percent of voters ultimately backed a party [The National Front] founded by a convicted Holocaust denier and where incidents of anti-Semitic violence are common.” In the U.S., anti-Semitic attacks are at their highest level in two decades. And some white supremacy groups have adopted Hitler salutes and swastikas in their racist and anti-Semitic campaigns.

Elderly Holocaust survivors have publicly expressed their concern that subsequent generations may not learn enough about the Holocaust to be vigilant that its horrors are not repeated. A new study commissioned by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany found that 31 percent “of Americans, and 41 percent of millennials, believe that two million or fewer Jews were killed in the Holocaust; the actual number is around six million. Forty-one percent of Americans and 66 percent of millennials cannot say what [the Nazi concentration camp] Auschwitz was. And 52 percent of Americans wrongly think Hitler came to power through force.” (Hitler was actually appointed as Germany’s chancellor in 1933).

Individual accounts of survivors make vivid and immediate the plights of ordinary people caught up in momentous historical events. And understanding the Holocaust may create an awareness of current waves of religious and ethnic genocide in places like Myanmar — or with the plight of refugees facing shifting immigration and asylum policies in this country. “There’s no way you can have the history of the Holocaust in your family, and not feel a connection to the current news cycle,” Lerman says.

After the premiere run of Cyla’s Gift at Taproot, Lerman plans to “take the show around the country and world, and continue telling the story.” She also wants to make a “dream trip” to retrace her grandmother’s path from Maniewicze to the U.S.

Lerman appreciates not only inheriting the stories Cyla left her, but also her spirit. “She was a strong, brave woman and in order to survive she had to fight for it,” Lerman says. “She also left me that legacy of standing up, and fighting back.”