It was not her first bad experience with Access — there had been plenty of times when nobody at the understaffed call center picked up the phone, when her bus ride took her on long detours, when she got dropped off more than an hour early for an appointment or was picked up late to go home. But missing the party at the bowling alley in White Center last year really stung.

“I’d scheduled the ride the day before my grandson’s birthday, but they never came to pick me up,” said Williams. “I’m the matriarch of the family and I’m not there and it’s not right.”

The 1990 federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires that government agencies provide equal access to public transportation. Paratransit serves people who cannot ride regular buses or trains by allowing them to book shuttle service that picks them up at their origin and takes them to their destination, rather than from bus stop to bus stop. Access uses passenger vans that accommodate 1-12 people and 2-4 wheelchairs to provide $1.75 rides to those who qualify.

Like most transit agencies, Metro pays private companies to provide Access service on a contract basis. First Transit currently does customer service and dispatch, and Transdev and Solid Ground provide the rides. Metro spends about $61 million annually to provide 900,000 rides to about 8,000 riders throughout King County.

The ADA mandates that paratransit service must be comparable to its “fixed-route” equivalent. In other words, it must provide service to anywhere bus, streetcar or light rail goes in the county and do so in about the same amount of time a regular transit trip would take. But, as riders and advocates have been pointing out for years and as a 2017 report by the King County Auditor makes abundantly clear, Access often falls short of that comparable standard.

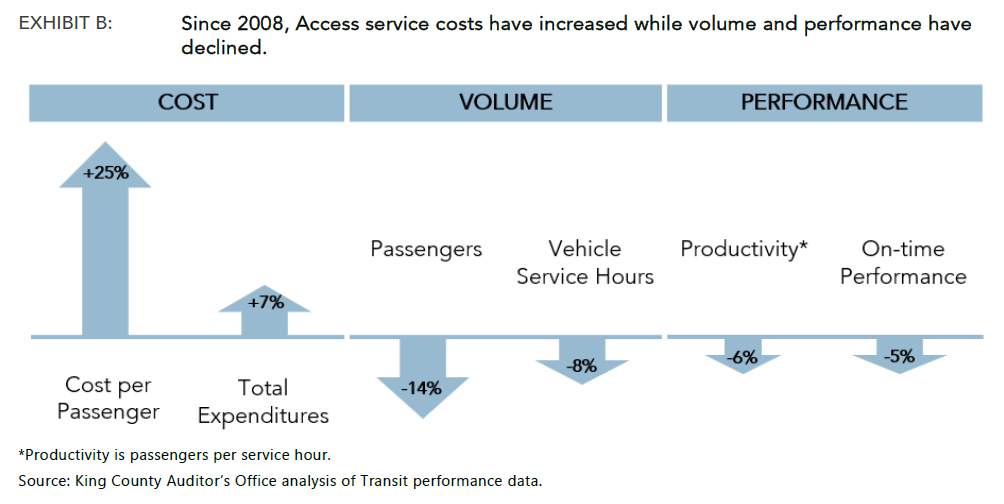

Riders are picked up excessively late, dropped off more than an hour early at their destination, trips take excessively long, the websites and call centers are difficult for non-English speakers to navigate, the service has higher operating costs than the national average and more, according to the auditor's report. It also said in the current system, there’s little disincentive for the contractors when they fail to meet guidelines and, because they’re paid by the hour, even incentive for taking excessively long trips.

“I’m talking about being ridden around the bus for two hours,” said Williams. “I’ve seen people on dialysis that are on the bus for two hours. They need to go straight home. They’re hungry and cold.” After missing the birthday party, Williams organized a group of about 10 riders to raise their issues directly to Metro.

Coupled with the work of advocates and the auditor’s report, the agency took notice.

“At Metro, we took the auditor’s report and what we heard from consumers very seriously and have taken steps to address that,” said Chrissy Russillo, Metro’s Access managing director.

The agency responded by creating a stakeholder task force, which Williams joined, to collect input from riders. It also implemented some immediate changes about pickup and drop-off times. Russillo said Metro already increased the number of vans and drivers to reduce delays. Starting Oct. 1, drivers will be required to deliver passengers to their destination no more than 30 minutes early, rather than the current 60-minute drop-off window.

Most significantly, it’s revamping the contract process to make significant changes in how the service is run and regulated in the future. In spring 2017, Metro began soliciting bids for a new five-year contract. In the wake of complaints and the auditor’s report, the King County Council told Metro to delay the bids and make significant changes to the service expectations before reopening the process this fall. Advocates and riders say it’s a good start, but worry that the agency hasn’t done enough to ensure Access will become the viable form of transportation its riders depend on.

For the new five-year operator contract, Metro has created three tiers of service level guidelines. Tier 1 is the least stringent and would have the least ridership increase. Tier 3 provides the highest service levels and would see the biggest jump in riders. The tiers set guidelines for acceptable drop-off and pickup windows, ride length, missed trips and more. The new contract will have more stringent penalties for failing to meet those service levels. For example, contractors will be charged $35 for every trip that’s 30 to 60 minutes late and $100 for being more than an hour late — something Metro can track through the van’s on-board computers. “It gives them incentive to figure out how to be on time,” said Russillo.

“Any one of these tiers would be a victory,” said Susan Koppelman, Seattle Transit Riders Union’s Access campaign organizer. “But Tier 3 is most similar to what riders and rider advocates have been lobbying for since 2017.”

Transit Riders Union, Disability Rights Washington and Washington ADAPT co-authored a new report highlighting problems with Access paratransit and advocating for the changes they wish to see Metro take with the new contract.

Koppelman worries that Metro will ultimately prioritize cost considerations over service quality and go with Tier 1. The agency does not yet have cost estimates for each tier, but said higher service levels will cost more. The tier Metro chooses will be decided in part by how much money the county council and county executive allocate to the program in the 2019-2020 budget.

No matter what level of service Metro chooses, advocates want to see greater oversight and enforcement. The county auditor’s report criticizes Metro’s current lack of oversight of Access compliance and Koppelman said the agency hasn’t made clear exactly how that’s changing for the new contract.

“We want to see the county’s proposal for how they’ll hold contractors to the promised service levels,” she said. “We want there to be transparency so we can hold Metro accountable for holding contractors to the level of service that riders deserve.”

Russillo said Metro plans to increase the number of staff dedicated to contractor oversight as part of the effort to increase compliance. Metro is also going to hire one contractor to manage all parts of Access operations rather than its current three.

In the long run, advocates want to see Metro ditch its public-private contracts and bring Access operations in-house. At the very least, they want Metro to do the ride scheduling and dispatch service.

“Bringing this in-house will be best for riders, workers and taxpayers,” said Koppelman. “Right now we are spending millions of dollars on for-profit corporations that have really bad track records.”

Given that Metro is about to sign a new five-year operations contract with an option to renew for an additional five years, Access will continue to be a public-private entity for the foreseeable future. The agency plans to run Access customer service in-house, however.

Metro hopes to have the new contractor up and running by summer 2019. Harriet Williams has her fingers crossed that things get better.

“I love Access,” she said. “I’m grateful that we have it. It just has to be fine-tuned. Make it better for the people who don’t speak English. Make it better for the developmentally disabled people who can’t tell the bus driver they’ve been riding too long. Answer the phones because it’s scary for seniors and people who ride the bus when they don’t know if they’re getting back home or not. If they take you away from home they’ve got to make sure you’re getting back.”

Correction: This story originally reported that Metro spends $91 million annually on Access. It spends $61 million annually. The story was also corrected to reflect the fact that Metro already has staff dedicated to contract oversight, but will add additional staff to provide oversight of the new contract.