The designation comes from national group United for Libraries, which over the last 30 years has awarded 33 other states with landmarks commemorating deceased writers including Spalding Gray, Margaret Mitchell, Ernest Hemingway and Dorothy Parker.

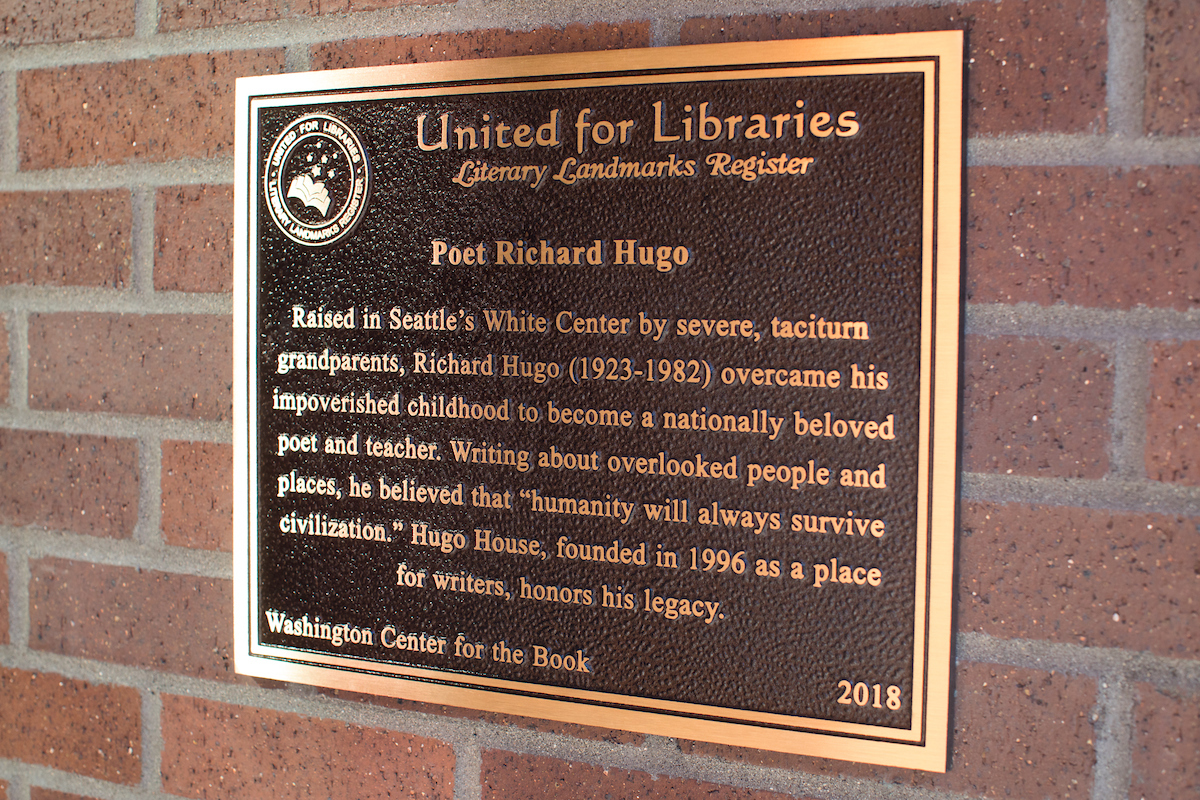

Washington’s first such certification is dedicated to local poet Richard Hugo, but instead of his birthplace or writing space, the plaque adorns the 11th Avenue entrance of a brand new, state-of-the-art apartment building on Capitol Hill.

Hugo House, the namesake literary center founded in 1996 by Seattle writers Linda Breneman, Andrea Lewis and Frances McCue, was originally located in a Victorian-era building that had long served as a funeral parlor — precisely the sort of structure on which you might expect to find a historic plaque. Writers loved the building (which Breneman had purchased with Linda and Ted Johnson) for its quirky charms, creaking floorboards (and alleged ghosts). But in recent years, as attendance at Hugo House classes and events increased, what once seemed darling was moving toward decrepit.

After trying and failing to get historic landmark status from the Seattle Landmark Preservation board in 2013, Hugo House began exploring other options for improving and expanding the space. With the Capitol Hill apartment boom, “mixed-use” facilities were all the rage, and in 2014 the building owners began working with developer Meriwether Partners on a plan. Weinstein A+U was selected as the architect for the new six-story, brick-clad apartment building, to be constructed on the same site. The Hugo House nonprofit would purchase 10,000 square feet on the first floor, for about half the market rate. In 2016, the Victorian was razed, and the $7.5 million capital campaign began.

Last weekend, the new Hugo House space (designed by Seattle’s NBBJ architects) threw open its thoroughly modern glass doors for the grand opening. Attendees standing in line for the packed party had a clear view of the plaque.

“We knew we had a strong case with Hugo House reopening,” says Linda Johns (of Seattle Public Library), who submitted the Literary Landmark application with Nono Burling (of Washington State Library) on behalf of Washington Center for the Book. Hugo House was the first location ever submitted from Washington state, and starting in 2019, Johns and Burling hope to establish two more per year. “Wouldn’t it be great to have a whole bunch, and map them?” Johns says.

The text commemorating Hugo begins, “Raised in White Center by severe, taciturn grandparents, Richard Hugo (1923-1982) overcame his impoverished childhood to become a nationally beloved poet and teacher.”

That’s another thing that stands out about the plaque — it’s perhaps the first instance of “taciturn” in a historic marker. (Asked whether all the Literary Landmarks use such descriptive language, Johns says, “No, the other plaques are pretty straightforward.”) But Hugo House executive director Tree Swenson says once they received the designation, they spent a lot of time going back and forth on the text.

“A plaque is permanent,” she says. “We had to get it right!”

Swenson worked with Hugo’s closest living friend, Lois Welch (former head of the University of Montana’s creative writing program) to perfect the language. “He’s written a lot about his growing up,” Swenson says of Hugo, “His [teenage] mother abandoned him, left him with her parents, who were not happy to be stuck with this kid... There was a lot of violence in the home.” Swenson says the first draft of the text described his parents as “something like mean and strict.” But Welch told her, “They weren’t mean, just poor people, frustrated by a difficult life, trying to raise a sometimes difficult child.” When Swenson suggested “severe, taciturn,” Welch said, “That’s it. That’s perfect.”

Working to get the words just right. Setting the scenes. Crafting the stories — it’s exactly what’s always been prioritized at Hugo House. And now emerging and established writers will be doing so in a building with fewer creaks, more intentional space and much better bathrooms.

Despite being barely a week old, the new facility is already inviting, with a lobby bar made from repurposed wood from the old building, diner-style booths for reading and talking about books and classrooms set at angles and painted different neutral shades, such that a glance down the hall recalls looking down an old-fashioned street of mismatched storefronts, a Triggering Town, as Hugo famously titled a book of essays on writing.

On the back wall, between the flexible theater space (no more obstructed views!) and the leafy patio that takes the place of the old staff parking lot, is another homage to the craft of writing: artist Spencer Finch’s “Sunlight in an Empty Room (Emily Dickinson’s Bedroom).” In this digital reproduction of a 2010 artwork (donated by Bill and Ruth True), a wide expanse of golden-hued wallpaper with a fleur de lis pattern is interrupted by rectangles of window light. Finch used time-lapse photography in the historic Dickinson home to capture and replicate the light as it moved through her room.

A recluse who had her own remote and taciturn parental figures to contend with, Dickinson wrote poem after poem alone in that room, the only visible movement being that of her pen and the light across the wall. The descriptive card notes that her poetry is “a testament to the mind’s ability to create an internal world far more vast than the external one.”

The sentiment ricochets across the building, past the generous new unisex bathrooms, and out the front door, where it echoes Hugo’s quote on the landmark plaque: “Humanity will always survive civilization.” A city changes. Our beloved old buildings are replaced with bright new ones, and the drive to create and connect persists, as if forged in brass.

Crosscut arts coverage is made possible with support from Shari D. Behnke.