Hours later, McKesson headed straight for the center of the protests, which had erupted in the St. Louis suburb after police shot and killed a Black teenager named Michael Brown.

It wasn’t long before McKesson himself appeared on news channels to address the issue of police brutality. A relentless witness to the protests on social media, McKesson is partly responsible for making the civil rights movement known as “Black Lives Matter” a household name. Since then, he has helped compile the most comprehensive data on police killings in the nation.

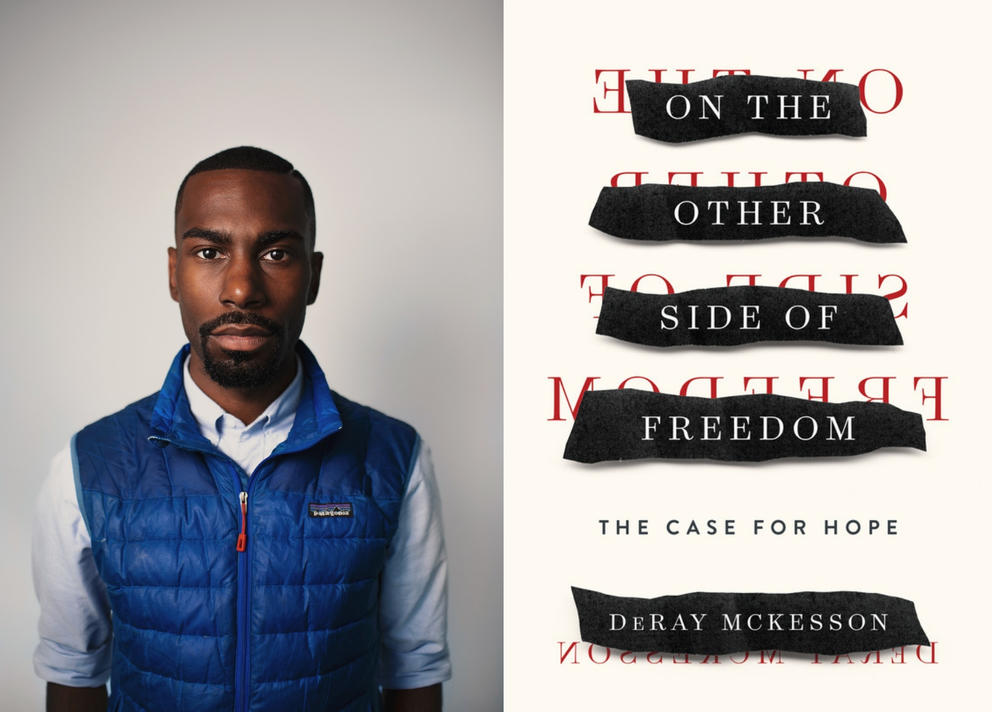

McKesson, host of the podcast “Pod Save The People,” is scheduled to be in Seattle Friday to talk about his work and his new book, On the Other Side of Freedom: The Case for Hope, at Benaroya Hall.

In the book, McKesson writes about his strained relationship with his mother, a former drug addict who left McKesson when he was just 3 years old; the sexual abuse he suffered at the hands of a relative of his father’s girlfriend; homophobia in the Black community and the challenge of “fighting for people who don’t think I’m worthy of fighting with;” and the time he called out former President Barack Obama on his use of the word “thugs” to describe protesters in Baltimore.

I spoke to McKesson by phone on Monday. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: One of the criticisms of the protests in Ferguson at the time was that activists didn’t have a clear vision or an established set of goals. Looking back, do you feel that criticism was fair?

I am always mindful that protests are not the answer, protests create space for the answer. And that’s what we were doing in 2014. If not for us being in the street, people would have forgotten about Mike Brown. Police violence wouldn’t have become a national conversation. So when I think about the work of 2014, it was about keeping the issue alive and being really clear that it’s not just Ferguson, it’s the whole country. And what makes St. Louis so unique is the city has the highest rate of police violence in the country. So there was something special about the locale. What we knew in 2014 was, Mike should be alive. That was the thing that we just carried with us every day. I think those criticisms were actually coming from people who didn’t quite understand the enormity of the problem.

Q: In the book, you talk very eloquently about this inability of people to see beyond their own lived experiences. You write: “Too many people claim to be 'woke,' but cannot see beyond their own experience.” Have you figured out ways around this problem?

Part of what I now understand is, we have to have other people do some of the cognitive work that actually gets them to a place where they can imagine what it’s like to have to make some of the decisions we have to make.

Q: Your writing on policing is reminiscent of the Abolish ICE movement. Would you agree with that or is that going too far? Do you want to abolish police in the same way others today want to abolish ICE?

Policing actually isn’t working, but people aren’t willing to say yet that it’s not the solution, so we should talk about thinking about alternatives. So with ICE, ICE didn’t always exist. There's other ways to enforce immigration laws. This isn’t the only way to configure the system.

What I’m pro is safety in communities that doesn’t require people to have guns, that doesn’t only rest in negative power, that people who enforce rules only take from you. I believe people in community can actually be responsible and are strong enough to manage the majority of issues that arise.

Q: You talk about your broken relationship with your mother and compare it to the broken relationship many African Americans have with America and its racism. You hope one day you will be able to look back at both without pain. What would it take to get there?

I’ve had a hard couple of days. I woke up yesterday really angry at Joan [McKesson’s mother]. Angry at her, because I just wanted a mother. I just wanted a place where I knew love lived. So I think I’m still working on it. I’m still working on what does it mean to reconcile? What does it mean to come together? I’m mindful that when we think about truth and reconciliation, that the truth comes first. So some of what I have to work through with Joan and my relationship with America is, we actually just have to be honest and candid, not in a way that is rooted in hurting each other, but we just won’t deny that things happened. My relationship with her is a reminder that it is easier said than done. It was easier to write that chapter than call her.

Q: It sounds like you remain very much pro social media, pro Twitter, though you acknowledge people like President Donald Trump have used it for ill. What have you learned after years of being so active on social media?

One of the reasons I follow so few people, some people think it’s an ego thing, but really it’s because I got burned so many times retweeting or amplifying things that weren’t true. I can only follow people that I know are only going to put true things on the timeline. I also ask more questions now than I did before.

Q: What did you learn from your run for mayor of Baltimore?

When I ran, people thought I was a sellout for running for office: 'How dare you want to be part of the system? You just used the movement to go inside. Nobody makes change from inside.' I got so much of that that it was kind of wild. Now nobody would say that aloud. Today everyone is running for office. We praise them for running for office. Trump, this moment, has forced people to realize you can’t just fight against people in power, we actually have to be those people.