The United States and Canada share the longest common border in the world: 5,525 miles long when you count the borders of the lower 48 and Alaska together. But unless you live in a border state, this dividing line isn’t on the average U.S. citizen’s radar.

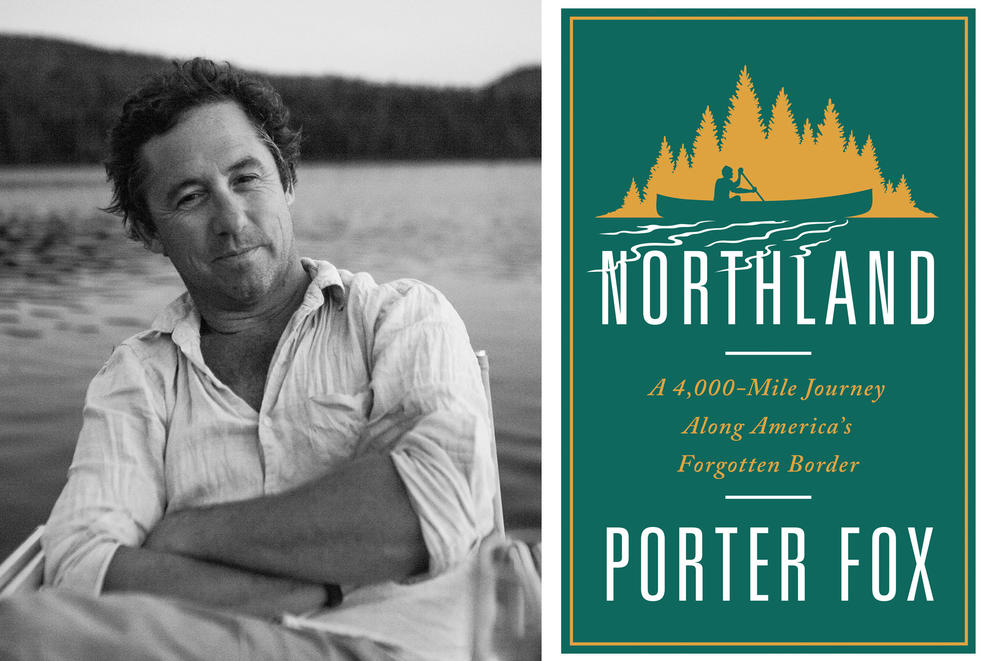

Writer Porter Fox sought to remedy American indifference to, or ignorance about, our northern border by traveling most of its length by canoe, freighter, car and foot over three years. His book, Northland: A 4,000-Mile Journey Along America’s Forgotten Border, explores the landscape, history and present-day state of affairs along the border. Heading west from Maine to Blaine, he takes note of the surveying errors that have affected some border communities. He also observes how citizens’ sense of national identity seems to soften when their social lives — and marriages and family connections — span a boundary.

Fox grew up near the coastal resort town of Bar Harbor on Maine’s Mount Desert Island. But his earliest, strongest sense of what life near the U.S.-Canada border is like came from boyhood summers spent at a lake resort in northwest Maine. In a phone interview earlier this month, the Brooklyn-based writer discussed those memories and was candid about the unexpected turns his cross-continental trip took. He also disclosed why Northland stops at Peace Arch State Park in Blaine rather than following the border all the way out along the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Here’s a condensed version of our chat:

What were some of your earliest memories of living near a border? And how porous was the border when you were growing up?

Every summer we went to a lake house up in Jackman, Maine. That’s five miles from the border. My family has had a place up there since 1909. Half the town’s Canadian, half the town’s American — and it’s kind of the same on the other side of the border. If you passed through enough times, if you were working at a mill in Canada and cutting wood in Maine, they’d just flag you through. They just got to know you. That’s the way it was for a very long time.

What kind of border experiences did you have as an adult prior to researching the book?

Prior to writing the book, I worked for Powder Magazine for 19 years and did a lot of trips to British Columbia. The Spokane crossing into British Columbia was pretty tough. I think they were looking mostly for drugs back then, marijuana, things like that. And it was actually the Canadian border patrol that was way tougher than the Americans. The Canadians — and rightly so — have been worried, maybe paranoid, about guns, drugs … America’s bad ways slipping into their country. Since 9/11, every single border crossing is hard. Every single border crossing is highly unpredictable. It costs American and Canadian businesses billions of dollars a year, literally, just not knowing how long the wait time is going to be, missing shipping deadlines and what-not. It’s almost like the unpredictability of it is more damaging right now than the actual daily situation on the border. … You just don’t know what to expect.

9/11 was a seismic turning point for the border. But the 2016 election must have had an effect, too. Was there a big difference between traveling before the election and traveling after the election?

It was huge. It was just huge. I mean, my project didn’t change in scope or direction after the 2016 election. But my interaction with people on the border changed drastically. I experienced a bit more — how do you say? — a little bit of hostility in Canada … like, just a bit of regret on the Canadian side for the fact that America seemed to be taking our northern neighbor for granted, seemed to be forgetting that they’re our Number 2 trading partner, our Number 1 foreign oil importer. Very, very important things that keep this country ticking. They sort of felt like we had forgotten all that — or certainly, our president had forgotten all of that.

The 2016 election also triggered a sudden surge in refugees trying to cross from the U.S. into Canada.

On the North Dakota line, between Lake of the Woods and Pembina, North Dakota, thousands of refugees were streaming north looking for asylum in Canada. And these are border crossings and border regions that really had been extremely sleepy until that point. There hadn’t even been that much human- and drug-trafficking across that. But these migration routes were quickly established going from the U.S. up into Canada. I think in 2017 it was 15,000 people. So that was pretty shocking to see. And, of course, all the headlines in all the Canadian newspapers were constantly: What are we going to do with all these thousands of migrants that are living in, not detention centers, but, warming centers — places that keep them warm and healthy. They didn’t really know where to put them. Pretty crazy.

The book makes clear that from coast to coast there’s a strong Native American presence in regions on the border that are remote from the main centers of the U.S. population. Were you expecting to find that, or did it come as a surprise to you?

It was a total surprise. And I’ll tell you what: most of the current issues that I cover in the book were a surprise on purpose. I started the trip with the intention of researching the border … how it was drawn, the relevant historical context, and what-not. But I didn’t research news topics along the line. I just let them come at me as I went from east to west. And I went from east to west very purposefully to follow the chronological development of the U.S.-Canada border. So I get up to Lubec, Maine, and I’m starting the trip off in Passamaquoddy Bay. I had never been to Passamaquoddy Indian Reservation, which I’m embarrassed about. But most people in Maine would say the same thing.

You were steered there toward Donald Soctomah, the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of the Passamaquoddy tribe, on St. Croix River along the Maine/New Brunswick border.

Somebody was like: “He and his tribe know the St. Croix watershed and river better than anyone.”

Soctomah and the Passamaquoddy tribe turn up later in Northland, donating a moose to feed the protesters at Standing Rock. How did Standing Rock first register on your radar?

I was driving across North Dakota and news of Highway 1806 being closed came across the radio. I pulled over. I looked it up. I read about Standing Rock. It was the very early days of that protest. I called the Morton County sheriff’s department. They said, “Don’t go down there.” Which immediately meant: “Go down there.” So I went.

The land of another Native American tribe, the Akwesasne, is divided by the U.S.-Canadian border, which creates real problems for them and has led to protests similar to Standing Rock’s.

The Akwesasne situation on Cornwall Island on the St. Lawrence River did get me pretty worked up about how unfair a lot of it seems. So connecting that to Standing Rock was just a shoe-in. I realized that there was this string of Native American reservations along the northern border that all held a lot in common.

There seem to be some portions of the border that you skipped: Vermont, New Hampshire and northwest Maine, for instance. How did you decide which parts to check out?

It was honestly what was the most interesting to me. Certain things like the Passamaquoddy Reservation connected to the Akwesasne to Standing Rock to the Lummi tribe. I had a whole section written about the St. John Valley — those northern regions of the Maine panhandle — thousands and thousands of words I just had to cut. It was just too much. You use the parts that fit the best. It’s a long border.

You mention a town in Washington State that, due to surveying errors, wound up with half the town “on the wrong side of the border.” I’m a Google Maps fanatic and have studied the Washington/British Columbia border pretty closely. But I’m not sure what town you’re talking about.

It’s Sumas. And there’s actually a terrific article about the town and about all the errors made in the surveying of that line, and how much it veers off-course. It’s pretty wild. It’s not straight at all. And I actually just recently learned that the 45th parallel, that goes across Vermont and upstate New York, does exactly the same thing. It veers up and down, and it goes up to 700 or 800 feet off-course. Which is a lot in a little town.

I was startled, coming at the book from a Pacific Northwest point of view, that you didn’t mention Point Roberts, which has no land access to the U.S. mainland, and that you didn’t follow the border right out through the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the open Pacific Ocean, or delve into the border disputes over where to draw the line between the San Juan Islands and Vancouver Island.

I actually did kayak that line, and I have a whole other story of sea-kayaking through the San Juan Islands along the border.

Has it been published anywhere?

It’s going to be published. We have photographs, some very cool drone footage. The way the book begins is kind of looking at this line appear out of nowhere from the ocean, and I wanted to go to the terminus of the line and see it kind of disappear.

Anything else about the trip you’d like to mention?

The North Cascades really blew my mind — the history of those fire lookouts, being on Winchester Mountain. I’m telling you, that was one of the most incredible nights of my life … sitting there alone, staring at the stars, watching the storm roll in, against the backdrop of this epic three-year journey … a physical journey, but also a kind of mental and writing journey to document the border. It was just terrific. I love those mountains so much. There’s just nothing like it. It’s beautiful.