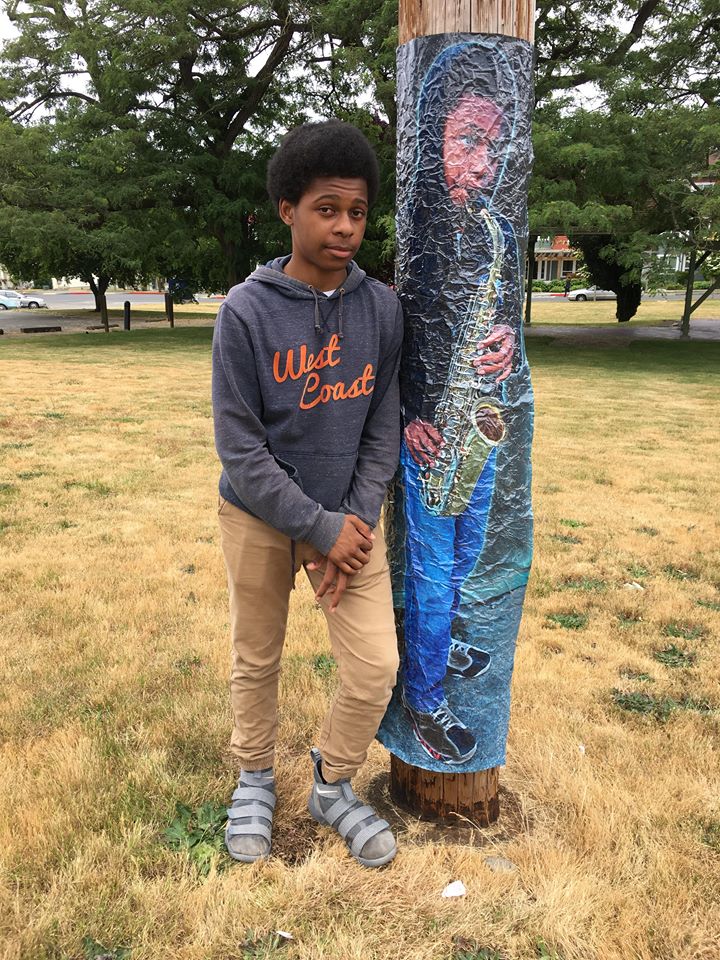

In June, the same image hung as part of an exhibit on the history of the Black Panther Party. An adhesive painting, the artwork was displayed on an exterior wall of Photographic Center Northwest.

“It was shocking to discover on June 9 that the head had been ripped off,” says Michelle Dunn Marsh, the executive director of the Center.

Marsh says that the same weekend the piece was vandalized, a nearby educational institution was tagged with graffiti “of a white supremacist nature.” She did not specify the institution because she did not have permission to reveal the name publicly.

In defiance of the earlier defacement, the Center reapplied two new versions to the outside of its building — and with support from the artist, involved others in the neighborhood. Marsh and Center staff members walked along 12th Avenue asking businesses whether they’d also like to display “Black Teen Wearing Hoodie: Reading Pedagogy.” Ten local establishments, including Seattle University's Hedreen Gallery, Café Presse, Southpaw Pizza, Pacific Supply hardware store, the Northwest Film Forum, Velocity Dance Center, Eltana Bagels, Jucebox, and the non-profit Artist Trust agreed to participate.

Since the second wave of installations, however, Marsh says the image has been completely torn down from the Center and twice from Café Presse. And just last night, the version displayed on the outside wall of the Hedreen Gallery was also removed. In the most recent instances of vandalism, there were virtually no remnants of the artwork left behind.

“It’s hurtful,” says Brown, the artist. “I don’t see anything controversial about my son reading a book.”

When Brown and her son lived in the Cooper Artist Housing residence in Seattle’s Delridge neighborhood, her six-year-old would run up and down the long halls, letting himself into his neighbor’s apartments. “Everyone thought he was really cute,” she recalls. As he grew, Brown wanted more space and began her journey south, first to White Center and eventually to Tacoma, where she bought a home.

Now her son Jaymin is 14. Last year, on the fifth-year anniversary of Trayvon Martin’s shooting death, Brown wondered: With Jaymin now standing 5’9’’ and his voice deepening, how many of her neighbors would be afraid of him walking down the street wearing a hoodie? Brown says one of her White friends confessed to being scared of Black men.

Says Brown, “I asked her, would you be scared of [my son]? And she said, ‘Well no, I know him!’ This kind of fear makes me afraid for my son as he grows up and goes out into the world, so I wanted to create a piece just showing a Black teenager wearing a hoodie doing things that he would normally do.”

Thus was born the series Black Teen Wearing Hoodie.

Asked whether she thinks the instances of vandalism were racially motivated, Brown is contemplative. “When they interact with the piece in a way that’s particularly vicious, I wonder, what is their motivation beyond that? . . . Is just my son standing reading a book that upsetting to people? That much out of the norm? And how would he be treated if he was walking down that street and actually standing in that space? I have to ask those questions.”

Other iterations of this same artwork had been ruined in West Seattle during a 2017 public art installation. Once at the beginning of the year-long display, and again toward its end, two images were destroyed. In one instance, the boy’s afro and arm were cut off. In another, the boy’s body was torn down; all that remained were his shoes. The vandals had spray-painted stubs sticking out of them, Brown says.

“I discovered that one during a walk-through to show off the art to the community. That was heart-wrenching,” Brown says. “To mutilate it in a way [as if] they were responding to it in a malicious way was disturbing.”

It’s a fair assumption that the vandalism was racially motivated, says Randy Engstrom, director of the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture. The Office co-commissioned the West Seattle installation. “There’s something about confronting our country’s racism that really challenges people,” he says. The vandalism “is a really terrible reflection of the stuff beneath the surface in our own city.”

Marsh, commenting on the recent vandalism on her building, says, “It’s malicious.” People have been trying to explain this was motivated by other reasons, she says, but she remains unequivocal that racism was involved.

“It’s not easy to face what it is,” she says. “At a moment that we are trying to improve our sensitivity and awareness to issues of collective and individual bias in this city, as well as in this country, I think it’s extremely telling that a lot of people’s first response is to explain it away.”

Marsh says she contacted the police about the recent vandalism, but has not yet heard back. Molly Mac, the curator of Seattle U's Hedreen Gallery, told Crosscut that she is in touch with campus public safety and is waiting to hear whether there was any security footage of the vandalism.

Café Presse did not say whether it plans to reinstall the piece for the third time. Photographic Center Northwest has one image up but has decided not to replace a second one elsewhere on its exterior.

There are six “Black Teen Wearing Hoodie: Reading Pedagody” images currently displayed on walls up and down 12th Avenue, with three more on the way. The Frye Art Museum told Crosscut it reached out to the Center after learning of the initial vandalism and plans to express its solidarity by displaying the artwork as well.

The new images have been produced with financial help from the Center and with donated labor from AlphaGraphics Seattle, which originally produced the artwork with Brown.

In a Facebook post yesterday, the Center wrote: “CapHill, we’re counting on you to keep an eye out with us and protect them.”

The hope is that the art will remain unscathed through the end of October.

Update: This story includes new information obtained after publication about the vandalism of the image at Seattle University's Hedreen Gallery on Aug. 13.