In a cease-and-desist letter sent to the mayor, a lawyer representing the union accused him of violating the United States Constitution's Equal Protection Clause when he instructed Portland police to not come to the aid of ICE officers.

The latest development in an ongoing battle between Portland officials and the federal agency, the union threat is shining a light on a tense month-long occupation and surfacing thorny questions: Does a police response amount to cooperation with the federal agency? And what local protections, if any, should be offered to ICE employees?

It all started earlier this summer at the height of nationwide anti-ICE demonstrations that came in the wake of the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy and family separations. During protests in Portland, described by the media as mostly peaceful, Wheeler tweeted:

"The policy being enacted by the federal government around the separation of very small children from their parents is an abomination. I want to be very clear I do not want the Portland Police to be engaged or sucked into a conflict, particularly from a federal agency that I believe is on the wrong track, that has not fully lived American values of inclusion and is also an agency where the former head suggested that people who lead cities that are sanctuary cities like this one should be arrested.

“If they are looking for a bailout from this mayor, they are looking in the wrong place,” he concluded.

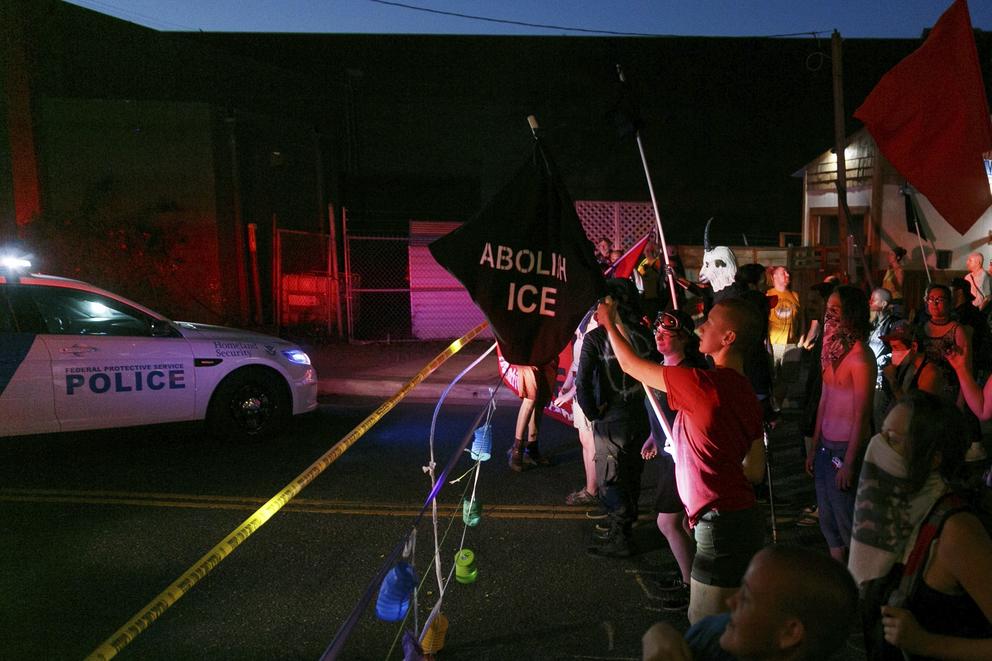

For more than a month as many as 200 demonstrators had set up a camp as large as 90 tents (complete with a well-stocked kitchen and onsite childcare), which surrounded the local U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement office, at one point temporarily shutting down the federal office. Police eventually cleared the camp on July 25, after Patriot Prayer leader Joey Gibson — a Washington-based activist who has a reputation for attracting White supremacists and violence and who is now running for a U.S. Senate seat representing Washington state — threatened to show up.

But before the camp was cleared, some who worked in the ICE office had called or emailed police for help. They now say police responded inadequately, even in the face of serious threats. If police choose to ignore future calls for help, the employees will sue, says union lawyer Sean Riddell.

“We understand that you have a difference of opinion with the current President of the United States, and some of his policies, but we fail to see why targeting the employees of ICE and leaving them vulnerable to violence, harassment and even death furthers a legitimate government interest,” Riddell wrote in his letter to the mayor. “Your policy has created a zone of terror and lawlessness.”

In a recent interview, Riddell said a representative from Federal Protective Service, which provides security for government facilities, emailed Portland police asking for assistance and that at least two other employees called for help. Riddell said he is also aware of other calls for services that have been reported as going unanswered.

The Equal Protection Clause, part of the 14th Amendment that Riddell’s letter references, has served as the basis of key court decisions, such as Brown v. Board of Education, which declared state laws establishing separate public schools for Black and White students to be unconstitutional.

Whether it can be applied to an organization like ICE is an open question. University of Washington Law Professor Jeff Feldman said it’s not that the government isn’t allowed to discriminate. Rather, the government cannot discriminate based on certain classifications, such as race, religion and national origin.

Being an ICE officer doesn’t fall into any of those classifications, Feldman said.

“The only thing that’s happening here is ICE officers aren’t receiving support for their own law enforcement efforts,” Feldman said.

He also pointed out that police prematurely interfering in protests could trigger a lawsuit, too, based on the violation of demonstrators’ First Amendment rights.

“I don’t doubt for a second this isn’t the easiest moment to be an ICE officer for all the obvious reasons,” Feldman said. “They need to be given protection when appropriate, but they don’t get special protection.”

Feldman said ICE employees might have more legal ground to stand on if they were speaking as private citizens and had actually been harmed during the protests.

Bill Araiza of Brooklyn Law School agrees, adding that states have the right to not cooperate with federal agencies. Police are also allowed to prioritize emergencies and community needs.

“This is all bound up in facts and narratives that the two sides have different versions of,” he said.

In a written account provided to Crosscut, one employee of Portland’s local ICE office said that when he tried to leave work to pick up his daughter from summer camp “7 to 10 individuals got in front of my car to block me from leaving.” The employee then drove through the grass in an attempt to escape, but protesters surrounded him again.

He said one demonstrator tried to let the air out of his tire to prevent him from leaving. Others shouted and threatened to beat him up. He called 911 several times, he says, and was finally able to meet an officer at a different corner. But he says protesters continued to follow him, calling him a Nazi and a member of the Gestapo. The Portland police officer said he couldn’t help and instructed the ICE employee to call Federal Protective Service.

Another employee named Nick also struggled to get his truck out of the ICE office parking lot and called for assistance. But again police said they couldn’t help.

“Told the police that we were going to get my truck out with or without them and that the next phone call they received would be a call of either the protesters or us getting assaulted and police still refused to assist,” he wrote in a note provided to Crosscut.

On Wednesday, Wheeler responded with his own letter calling the accusations lobbed against him by ICE’s union “inaccurate” and “inflammatory.”

“I want to be clear that the Portland Police Bureau does not police based on the content of speech. In this case, I have consistently stated that I did not want the Portland Police Bureau to be engaged or sucked into a conflict for the purpose of securing federal property that houses a federal agency with their own federal police force,” Wheeler wrote.

“While Portland Police were not engaged in removing protesters from federal property, Portland Police made clear to Federal Protective Service officials that local law enforcement would respond to calls for service at the demonstration site that have an immediate life safety concern.”

Referring to union attorney Riddell, Wheeler said, “In discussions with our attorney you were unable to make any substantive claim, instead stating that you ‘have unconfirmed reports from sources that I am not at liberty to disclose that assert the City of Portland did not respond to 911 calls.’”

Requests for comment from ICE’s national union went unanswered but Chris Craine, president of the union, told Willamette Week, which first reported on the back and forth between ICE and Wheeler, that police had allowed protesters in Portland go too far.

“Every person in law enforcement knows there are few things as dangerous or as unpredictable than an angry mob," Craine told the weekly. "No one could have responded quickly enough to protect our employees who were trapped inside this building. All of this because the mayor of Portland has a beef with the president of the United States."

Riddell, for his part, maintains “the mayor is avoiding the issue.”

“He allowed an unlawful, unpermitted encampment to take over part of the city and harass his businesses and harass his citizens to further his political agenda.”