Crosscut: Is there something particular to Seattle that allowed David Meinert’s sexual misconduct to go on for as long as it did? And on the other hand, is there something unique about Seattle that can facilitate actual change?

Johari: When it happened, when I read about it, when I heard about it, the first thing I thought about was not so much [Meinert], it was, Oh my God, how tough for all of these women to try to survive in this teeny little high school of a city… Especially knowing afterwards who some of them are, going, “Wow, you really didn’t think that you had enough power?”

Jasper: I think one of the things that does make Seattle strong is the fact that we’re small, that we know each other, that we can come together. That something like this [conversation] can happen very quickly, that’s a strength. When somebody like Dave Meinert is exposed, then the small community can be very powerful. Also, it’s easy to be a big fish in a small pond and when things become emotional and personal, it feels so much more complex. I think that’s the curse.

Johari: We haven’t even talked about the real power of this town. The real power is tech, and that is not being represented at this table. We can kind of be the test market for what could and should happen, but we would be remiss if we didn’t think that this was happening in [the tech industry]. To really exact the change that we want to have in the supposed liberal town that we live in, it would have to affect techies. Because that is where privilege is really happening. You’re making six figures and you’re a guy? And you’re 27? You got your second Tesla? That’s a whole other mindset.

Crosscut: Would some kind of legislation be effective in changing the culture?

Stowell: You can’t legislate people to be good people, but you can arm them with education and you could teach them what’s right and wrong. What an opportunity we would have if in our K-12 education system we started talking about life skills, with particularly gender life skills as a curriculum.

De la Vega: I have seen legislation impact culture. Even the legalization of marijuana has changed our culture quite a bit. I also think that we shouldn’t negate legislation.

Marshall: Legislation could help us.

Stowell: I think this is an issue that affects all women, all cities, all walks of life and it should really be a state and national legislated issue.

Crosscut: Angela [Stowell] and Miki [Sodos] mentioned the “no shift drinks policy” you’ve instituted at your restaurants. Are there other things that could be done?

Sodos: I think raising statutes of limitations, making sure that certain public services have cameras and forcing businesses to properly document stuff so that there can be at least a pattern of, “This particular manager had this incident.” I mean, they do it for liquor, so why not for sexual harassment? Making it like, “There were no issues with alcohol tonight,” “There were no issues of sexual harassment tonight.” So there is something to track.

It is a really hard thing to legislate but I think the statute of limitations is ridiculous because sometimes it takes three years for a woman to just even think about it. They just push it to the back and ignore it.

De la Vega: They compartmentalize.

Sodos: You still have to go to work and you still have to do your thing.

Marshall: How does a creep like that get so fucking successful?

De la Vega: Because we were all so silent, women are very silent, we are very afraid to speak out. That’s the reason. I also think, as a woman of color, I just want to make a bid for not dividing so much. I think that in the liberal community we are very siloed.

Crosscut: Do you remember when Mia Zapata was killed and the Home Alive self-defense organization sprang up? Again, that’s women having to do the work and say, okay, we’ll learn self-defense. But it seemed like it was such a universal rallying cry, like, we’re going to do something about this. So what is the Home Alive of sexual harassment?

Sodos: Meinert wouldn’t have gotten so far if the men around him… it’s bullshit to say that they didn’t know what was going on. These men need to get involved and actually say something. I mean if you don’t say anything, you’re thinking it’s okay, whether consciously or subconsciously.

Jasper: That’s exactly right. I’m impressed with how quickly so many of his partners actually got him out right away, but I totally agree there’s still silence. At a time like right now, that’s when you really need that alignment of words and action.

Marshall: I read a couple of years ago that there’s two things that define company culture: What it takes to get promoted and what it takes to get fired, and everyone in your organization needs to know that. I think that’s really pertinent to this conversation. What it takes to get fired — everyone needs to understand what harassment is.

For instance, we have a dishwasher that sexually harassed some women that work with us; he asked them to show him their underwear and they said, “No, we will not show you our underwear.” He said, “I’m going to keep asking,” and that guy had to be fired. It was immediate, it was three minutes later he was gone and you can’t come back.

I feel like everyone in the organization needs to understand that these are the things that absolutely will not be tolerated because that sets a precedent. No ass slapping, no “show me your underwear.” Everybody needs to understand very clearly what the rules are and there need to be multiple points of contact you can report to.

If your immediate supervisor is harassing you, you need to have the phone numbers of three other people that you can go to immediately. I mean, I have had my ass slapped so many times because I’m a career waitress, my entire life. I’ve been in hospitality, working for tips, getting my ass grabbed, getting my boob grabbed.

Sodos: I’ve had that happen as an owner. Guys are so vastly unaware that you don’t sexually harass your owner.

Stowell: I had it happen on Friday night at the Pearl Jam show.

Sodos: Oh, God.

Stowell: I had somebody grab my breast at the Pearl Jam show. I was walking up to the bathroom and I dropped my purse and I stood up and this little asshole just ...

Marshall: It’s 2018!

Johari: I hate to say it, but I think the way to change that script, it has to be packaged and done in this completely cool, pop media way. It’s the only way that is going to have an effect.

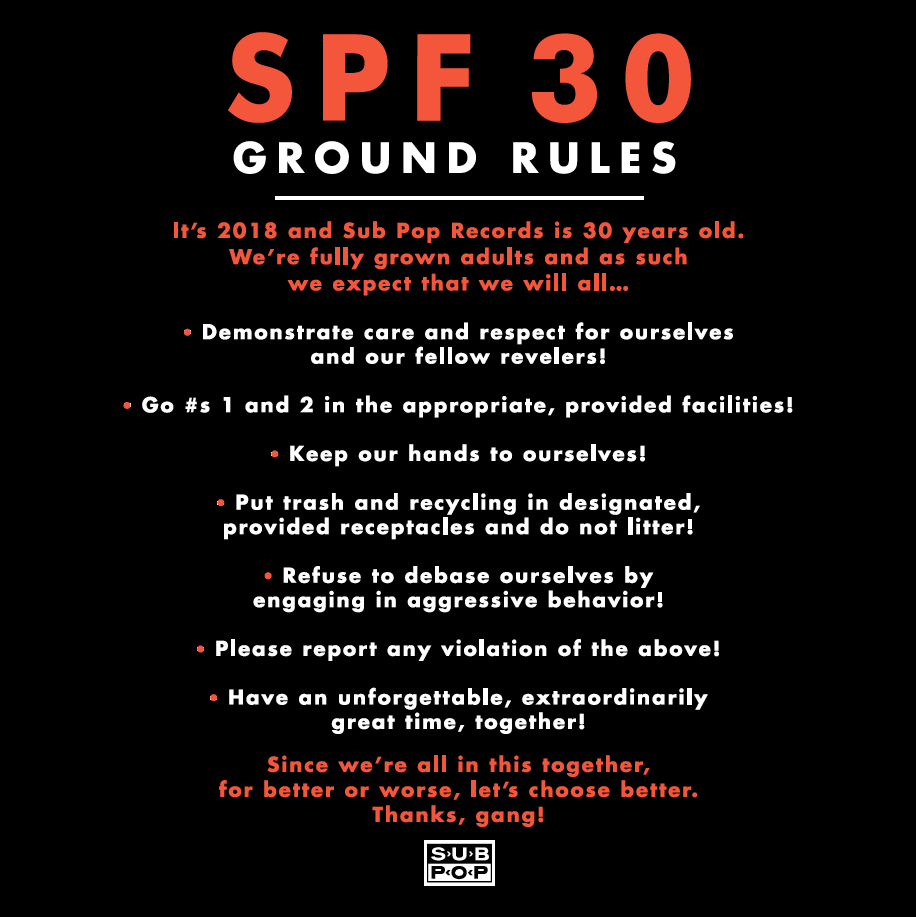

For example, there was just the Sub Pop party; Alki was smothered full of people. Sub Pop is considered this thing that they want to be a part of. To be a guy who is without a doubt not interested in toxic masculinity, who is not practicing rape script, who is not an aggressor or a predator — it has to be cool to be that guy.

You’re talking about the dishwasher, but what if the panty guy is [a powerful businessman]? How does that person become accountable, that 1-percent echelon of predator? Somehow our society has to turn it into this thing where you actually self-police and you think of yourself as a scumbag.

De la Vega: I know men who would have completely turned a blind eye who are not turning such a blind eye today. I think that there’s some efficacy in what’s been going on.

Jasper: Some of the things that we did around that [Sub Pop] festival is we created a code of conduct and we had signs out that said, Keep your hands to yourself, don’t touch people. We had artists stop sets if they saw something. Father John Misty, at the end of the night, had someone thrown out because he was being aggressive with people in the crowd.

Johari: It has to be Fugazi, the Melvins, you know, the people who are considered part of this cool culture to be the ones that are the poster dudes of this thing.

Jasper: They have to push for it. And it’s starting to happen regularly, stopping a music set. The other thing I did that I hadn’t done at any of our other big events, I went down two hours early when I knew that the cops were going to show up.

I talked to all of those clumps of police officers and told them what was happening in our community, that there are sensitivities with women and that we wanted everybody there to feel as safe as possible. I also talked about the fact that at [Capitol Hill] Block Party there were multiple women who were groped, and, in one specific case that I know of, the woman went to a police officer and said, that man just did this thing to me....

Sodos: But they have to actually see it…

Jasper: Yeah, because that police officer didn’t see it, which I think there is a way to address that. Even if you didn’t see it, you can say, “Hey. I have my eyes on you, did this happen?”

Sodos: I think it was last year, I was unloading equipment right next to Grim’s and two men, after a little bit of conversation, pulled out their genitalia and started swinging it at me. There were like hundreds of people around me and I was by myself, waiting for my bandmates to come. I get real angry in those kind of situations and I have a weapon so I put my knuckles on and I had to push one of them and I threatened the other one. And then all of a sudden I'm a crazy person.

Luckily some of my bandmates came up and they were able to kind of squash the situation. I turn around and there’s cops chatting about 15 feet away from me and they weren’t doing anything — I had six men surrounding me with two of them with their genitalia out.

Jasper: Oh my God.

Sodos: I’ve yelled at the cops on Capitol Hill quite a few times because they let so much slide. All they would have to do is walk past, make their presence known, but they’re having an internal conversation about whatever. The education in the police force... on so many different levels….

Johari: I’m personally not that interested in extra legislation that gives police officers the possibility to come and disproportionately clock Black folks and Brown folks.

Sodos: Yeah, because if it was six Black men surrounding me, they probably would have noticed. But it was six 22-year-old White dudes with ponytails.

Crosscut: One of the questions we wanted to ask you was what advice would you give to a young woman who is entering your field and wants to be successful?

Johari: Take Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

[Group laughs]

Johari: My father was like, “This is my first kid, it’s a girl.” I started martial arts early. Somebody was teasing and saying, “Oh I remember you in Hell’s Belles and you threw this guy off the stage.” Sure, it’s my character, but I know a lot of guys who have daughters and I’m always telling them, “Put them in martial arts. Put them in martial arts like they’re brushing their teeth and say you have to do this until you reach the last belt.” Because then it builds the confidence. It’s not going to prevent anything from happening but at least she has something.

Jasper: We do self-defense at work.

Sodos: Part of me would be like, don’t get into this industry, it’s damaging in so many different ways because of sexual harassment, alcoholism and drugs. But then I love this industry because I do feel like it’s kind of one of the last industries where you can pick up your boot straps and make something out of yourself.

Jasper: I feel like this industry is the only place I’ve ever found where truly I can be myself and I so appreciate that. We always need more women in this industry — that’s what will make it better and stronger, and that will bring some change.

I meet regularly with young women who want to understand the music industry a little bit better, and hopefully I’m able to shed some light there. I encourage them to come in and to be strong and be unabashedly themselves — to feel like they are coming in as an equal to anybody.

I think just having the confidence, not that that’s an easy place to get to, but I mean, that’s where we have to get to — all of us.

De la Vega: I mentor young women sometimes in my field and I try to have dialogue with them about having “healthy entitlement.” I think for artists, in general, it’s very difficult, and specifically for female artists and female artists of color. I think the conversation around how to have healthy entitlement is to advocate for yourself.

Marshall: I’ve never heard that term, that’s a great term.

Jasper: Yes, it is a really good term.

Marshall: I would say to women coming into the hospitality industry, open your own business. I had no money; you can do it on a shoestring. There is power in being the boss.

Sodos: I do think working in this industry makes women very, very strong — you have to deal with harassment, you have to deal with the douchebag customers. I was very timid coming into this industry and not now, and it is because of who I worked with, good and bad. It breeds strong women… they realize, I can put up with anything.

Crosscut: Karen [Maeda Allman] and Angela [Stowell], any advice for young women entering your fields?

Allman: I think that in the book industry, there is more of a veneer of civility and …

Johari: Although Sherman Alexie did get mentioned.

Allman: Well, what do you do if you have men in your community who have done significant positive things for our community — I’ll speak to my own Asian-American community — who on the other hand have treated women abominably? I mean they have both sides to them, and what do you do about that? They are not out there raping people, but there’s abusive power, there is harassment and it’s tolerated. How do you deal with that? It makes me probably twice as pissed off. How do you get people to take responsibility and not totally shun them for their whole lives? As you can tell, I’m conflicted.

I think for young women coming into our community, one of the things that we try to do is to make people not feel so alone. If something is going on, we want to know about it and we want to respond — if that’s with a customer, if that’s with an author — we want to know. It doesn’t have to be some really extreme thing. We’re all looking out for each other. I think it’s just a different environment [than the restaurant/music industry], but in a way, it can be more insidious because maybe it’s more subtle.

Stowell: I actually would encourage people to go into this industry because I do think, by and large, the restaurant industry is one of the best in the country and we band together like probably no other city that I know of.

This is a great opportunity. I came from nothing, put myself through college waiting tables, and my advice is do some research, go into the place where you might work. Sit at the bar, see what kind of culture that restaurant or bar provides and choose to work for the people who care about their employees.

I would also say that it’s important to see that for yourself, especially as a woman — and this goes for front of the house or back of the house, you just have different issues. If you are in the front of the house, you probably have to stand up to the customers a little bit more and know where your power is. You have the power to serve them a drink or not serve them a drink. And make sure you’re working for people who back you up. That’s really the number one thing I want the men and women who work for us to know: if somebody is coming in and being inappropriate, we’ve got your back and we’ll ask them to leave. We’ll ask them never to come back. Align with people who have your same values.

For the back of the house, make sure you know what that kitchen culture is like. If you are a female and going into a super-bro culture, just know what you’re getting into. It doesn’t mean that you can’t advance your career, it doesn’t mean you can’t eventually run your own business. But I think young women especially need to hear this: there’s not always going to be someone there to take care of you. You have to take care of yourself.

Standing up for yourself and speaking out is an important step. Younger women that I work with have a really hard time being bold and being… what was the term that you used?

De la Vega: Healthy entitlement.

Stowell: Having healthy entitlement.

De la Vega: Addressing the absence of the male voice, what if we literally ask the men in our lives, would you be willing to be a male role model? Would you be willing to speak out? Like, really actively asking men around us to do that? That takes the teaching off of our plates to some degree and gets men more involved in doing some of the work.

Jasper: I’ve done that.

De la Vega: I feel like I could actively be braver about that. The other question I had is if you were a woman speaking out publicly, how would you want the community around you to respond?

Jasper: I would want to feel like they had my back.

Marshall: I want two words: believe women. If everyone said that it would be great.

Johari: Sorry, I have a problem with that one. I think it’s great for us to have the intent to believe women, but I also feel like it depends on which community you come from.

As a Black woman, when something happens, we first have to see who’s involved before we decide which way we want to go. We have to see what is going on there, partly because [Black men] have already been disproportionately accused of things by particular women — specifically women who were not women of color — and incarcerated because of that.

Sometimes the women’s movement, in my opinion, benefits particular women but not all the women. If we’re talking about Sherman Alexie — maybe there was a conversation that also needed to be had then. No one is discussing the disappearances of indigenous women on reservations. And in this particular situation, when people are talking about women, we are not talking about all women, we’re talking about specific women.

Stowell: There is this larger racial bias piece that we have to talk about. I think you’re exactly right, what you were describing happens disproportionately to men of color, especially African American men. The systemic bias makes it so that men are wrongfully accused.

Johari: A lot of times when you’re talking about, “Well, maybe we should talk to the police officer,” for me it is like, I don't want to have anything to do with that. If something happens to me, they’re the last person I’m going to call.

For me personally, it becomes, who do you know? Who are the women that I know that I can count on. If it’s a young woman who’s like 12 or 13, I don’t know if they have that much of a circle. For some of us who have been assaulted at 12, 13 and 14, even our family, our friends, our community didn’t believe us.

To me, it’s not so much about what can we do for the young ladies. I still believe it’s what can we do to change this male script? What can we do to affect the male community to get them to stop doing it?

Sodos: If I can change one little girl who is bummed out because something bad happened to her and she [realizes], “Oh, this girl went through what I’m going through,” then that’s what would be important to me. Not necessarily for anybody to believe me or support me. Obviously, that’s nice but I don’t think it’s necessary for myself.

De la Vega: Right, so what’s an effective response?

Johari: When I said that about Ladies Who Lunch, I really meant it. We know each other now. We are connected; we are less than a degree away from each other. Then we have a group that gets started — including the music and all these industries, our connections and our intersectionalities — we start a group that is consequential and not wait for anybody else or legislation. To me that’s the first thing.