There are also clues within the sanctuary of Mount Zion which, not insignificantly, is styled like an African hut, that changes are afloat: The modern screens facing the congregation flash the different ways in which members can give monetarily to the church, which includes an option to donate via text. And Stallings himself represents a chance to look ahead for new directions.

At a recent service, when Stallings was out of town, another pastor at the church, the Rev. Dr. Patricia Hunter, delivered the sermon instead, referring to Stallings as “a breath of fresh air.” Some of those sitting in the pews shouted “Amen” in response.

Stallings, 73, became Mount Zion’s interim pastor in January after being approached by leaders of American Baptist Churches USA, the fifth largest Christian denomination in the country, made up of approximately 5,000 local congregations and 1.3 million members. Stallings was living in New York City at the time and had happily retired from American Baptist Churches of Metropolitan New York, a regional affiliate of American Baptist Churches USA, in 2015.

But then the Rev. Dr. Marcia J. Patton, formerly the executive minister of the Pacific Northwest affiliate of American Baptist Churches USA, asked Stallings to move to Seattle to help Mount Zion “get a vision for its future and make sure that vision is owned by members.”

“I tried not to come here,” Stallings said, expressing reluctance about taking on his new role at this late stage in his life. But after a visit to Seattle in November, Stallings felt that providence had nudged him. “I needed to come here and do what I could.”

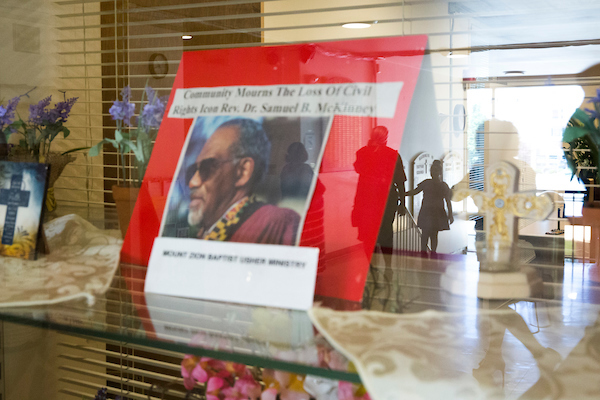

Since the 1998 retirement of the Rev. McKinney, its 40-year-pastor who was friend to civil rights leader Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Mount Zion has gone through other transformations. (McKinney, who was instrumental in bringing Dr. King to Seattle in 1961, died in April.) In 2005, after pressure from the congregation, a pastor at the church, the Rev. Leslie Braxton, resigned. Braxton now leads New Beginnings Christian Fellowship in Kent.

Then last year a second pastor, the Rev. Aaron Williams, stepped down. Of the latest split, Stallings would only say that Williams had lacked certain strong leadership qualities and had been a “mismatch” for the congregation. “It’s kind of like the country right now,” Stallings said, comparing the departure of a pastor who doesn’t serve the congregation well to President Donald Trump leading the nation.

Church membership across the country among mainline Baptists has remained steady and even increased slightly, according to a 2015 Pew Research Study. In 2014, 37 percent of Baptists reported attending church at least once a week compared to 33 percent in 2007. Overall, however, church attendance among mainline Protestants is down in the United States. Mount Zion itself has seen its membership decrease to about 800 members today from a peak of almost 3,000.

Stallings hopes pushing the church toward reconciliation will attract both lapsed and new members. “I believe Mount Zion has a significant future,” Stallings said.

He called Mount Zion a “historic congregation that is going through a time of transition.” (On Wednesday, Mayor Jenny Durkan will formally designate Mount Zion Baptist Church a protected landmark in the city, partly because of the key role it played in Seattle’s Civil Rights movement.)

One of the other ways Stallings hopes to bring Mount Zion together is through a new sense of purpose. As the Central District continues to gentrify, Mount Zion — located near a Trader Joe's and Planned Parenthood — is under pressure to adapt.

“Mount Zion has made a theological statement that it’s not moving,” Stallings said. At the same time, Stallings emphasized the church’s doors are open not just to the African American community it has mainly served over the years but to everyone. “We are comfortable with people who are seeking to live out their discipleship,” he said, noting that back in New York he himself was part of a famously multiracial congregation — Riverside Church.

But Stallings admits the transformation of the neighborhood prompts the question: “What is it [Mount Zion] being called to in this community that is no longer made up of persons who are African Americans?”

“You have to make your worship service represent the people who are sitting it the pews,” Stallings said and think about “what Mount Zion is called to now and not so much to what Mount Zion has been.”

For now, Stallings and other leaders at the church admit they’ve missed opportunities to raise Mount Zion’s "prophetic voice.” While the church owns a housing facility across the street — McKinney Manor — Stallings believes the congregation needs to be more outspoken about Seattle's housing crisis.

Rev. Hunter has also accused the church of being too bogged down on who gets to sit in the pulpit and, as a consequence, being too silent with regard to modern day civil rights movements like Black Lives Matter and the Me Too movement.

Members of the congregation, for their part, seem to agree with the leadership on the church’s need to take a more forceful stance on certain social issues. The other Sunday, after a boisterous choir had sung “Hallelujah Anyhow” and a baptism, Stallings mentioned that the city should have a policy that ensures everyone here has housing. Those sitting in the pews erupted in applause.

That day Stallings also seemed to sense an opportunity to personally welcome those visiting the church and introduce the idea that, they may want to return. He walked from the lectern into the aisles and stretching out his arms, looked directly at those in attendance, noting “the doors of Mount Zion are open” for those who are looking for community.

Harry Bailey, a former interim Seattle police chief who heads Mount Zion’s board of trustees, said, “People think that because there’s a change in leadership that Mount Zion is closed.” But Bailey said, noting that he believes Stallings is the “right person for the job” of interim pastor, echoed, “we’re open for business.”

“We got to understand our past,” Bailey said. “We want to make sure we build on that.”

But we also have to “move forward in today’s world.”

Jeri Harris, a lifetime member of Mount Zion who grew up in Madrona, is part of a committee made up of approximately 13 members at the church who, along with Stallings, are helping discern just how to press forward. Harris said the church coordinated a couple of healing sessions after the previous pastor, Rev. Williams, left but that “Rev. Stallings is a great asset to us right now. He’s a teacher, he’s a coach, and he’s a leader.”

“I’m excited about the future,” Harris said. “I’m feeling very positive about where we are right now.”

Editor's note: A correction was made regarding Rev. Dr. Samuel B. McKinney's retirement. He retired in 1998.