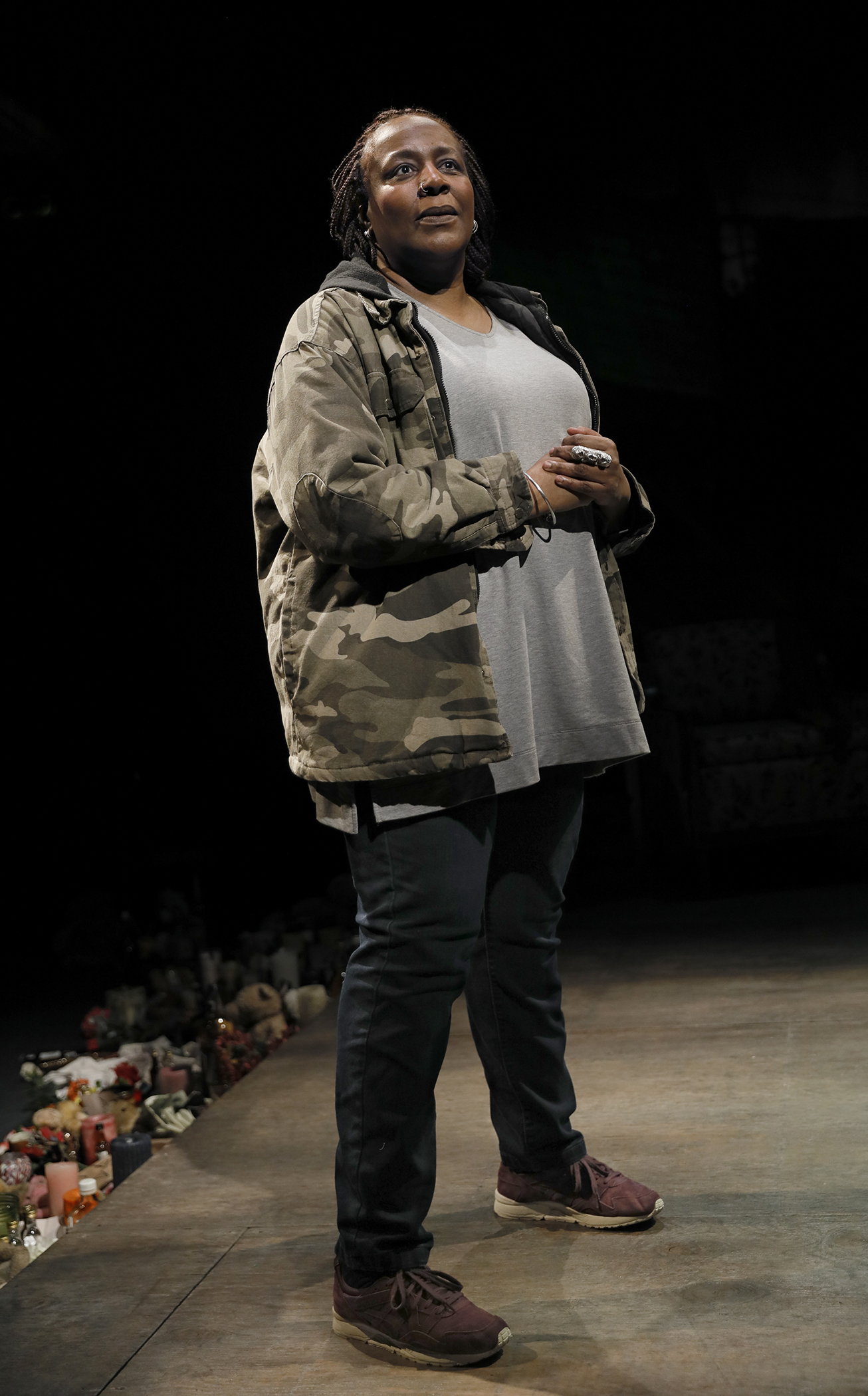

Now the native New Yorker is going solo in Seattle again, in the much anticipated Until the Flood, which she wrote and stars in (at ACT through July 8). This piece is more topical than autobiographical, but is just as deeply felt.

Taking as her source material the 2014 police shooting of Black teenager Michael Brown and its explosive aftermath, Orlandersmith wrote the play for eight characters — male and female, Black and White, angry and subdued — living in and around Ferguson, Missouri, the St. Louis suburb where the Brown incident occurred.

Taking as her source material the 2014 police shooting of Black teenager Michael Brown and its explosive aftermath, Orlandersmith wrote the play for eight characters — male and female, Black and White, angry and subdued — living in and around Ferguson, Missouri, the St. Louis suburb where the Brown incident occurred.

Quick recap: an unarmed recent high school graduate suspected of shoplifting a box of cigars in a convenience store, Brown was fatally shot by a White officer — Darren Wilson — after a brief altercation between the two men. That act sparked weeks of protests in Ferguson, adding fuel to the raging national debate over the treatment of young African American men by police.

In Until the Flood, Orlandersmith delves behind the headlines, into the personal impact of the shooting and the racial unrest that followed. Before opening her run at ACT, she spoke with Crosscut about the genesis and creation of Until the Flood (the title echoes a line in a poem that closes the piece).

This interview has been edited and condensed.

How did you decide to do a show about the Ferguson situation?

The St. Louis Repertory Theatre approached me. Seth Gordon, the associate artistic director, wanted someone to write a piece about Ferguson and race. He wondered, how can we talk about race? What’s the best way to do that? Theater.

What kind of research did you undertake for the show?

In 2015, the theater arranged it so I could meet a lot of local people and talk with them about how they felt about Ferguson, about Michael Brown. I didn’t tape them. I told them up front, “I’m going to be creating composite figures. I’m not like [documentary theater performer] Anna Deavere Smith — I’m not going to be playing you. But I really want to know how this incident impacted you.” I said, “Your story affects me personally — as a woman, as an American, as a Black person, as a human on this planet.”

How did people feel about looking back on such a difficult period?

There is certainly this thing called Ferguson Fatigue; the community was tired of being associated with race. Some people were still grieving, and some were so damaged by what happened that they didn’t want to talk about it anymore. But they had to acknowledge that the racial problems were still going on.

What stood out to you about the community?

There are these towns within towns in the area where the races are still segregated. And in Ferguson, cops were busting Black people left and right, for nothing — for driving too fast when they weren’t, so they could fine them and keep the money coming in.

What did you decide to focus on in the piece?

You’ve got this subject of race, and this area that’s highly racist. But then you’ve got the individual people, and the individual stories of Michael and Darren, who were in some ways amazingly alike. Both were born to teenage mothers, both had unsettled lives, both were big tall big guys. I think they’re the flip sides of the same coin.

Brown’s parents were very visible in the media during the Ferguson protests. Did you speak to them?

I met Michael Brown Sr. I looked into his eyes and saw he felt he’d failed as a father. He was still in so much pain. I didn’t interview Michael’s mother [Lezley McSpadden]. She seemed to be pumping the media. She hadn’t copped to the fact that she’d been a teenage mother moving from place to place, and her mother had been a teenager when she had her, and the effect that had on her son. [McSpadden has since written a memoir, Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil: The Life, Legacy, and Love of My Son Michael Brown, that has been optioned by Warner Brothers for a movie.]

How did you derive the composite characters?

I based them on how people I talked with responded to me, what I sensed was going on with them, how I think human nature works. Then with my director Neel Keller I looked at what we thought were the strongest characters and the array of feelings. I’m a theater worker. We went with the stories I thought were the strongest as theater.

Who are some of these characters you play?

We have a Black woman named Louisa. She’s in her 70s. She remembers racial unrest in the 1960s and looks at the way history is repeating itself. There’s a young man called Hassan who comes from a background like Michael’s, and you see his fear and stress living in that environment. There’s a White cop, Rusty. He’s a good old boy, but he’s not like the cliché of a good old boy.

You performed Until the Flood at St. Louis Repertory Theatre in 2016. What was the reaction?

I was very nervous about doing it there. But the response was lovely. People were very appreciative.

You’ve also had successful runs in New York, Milwaukee, Chicago — next year you’ll perform it in Portland, OR. What do you want to accomplish with the show?

I’m not a politician. I just hope I can invoke and provoke conversation. It’s such a hard time now in our country. It’s very much like the 1960s. We need to talk.

Ferguson was wrenching on a national level, but it spurred a lot of anti-racist activism. Do you believe the country can eventually become less divided, more racially equitable?

I like the way kids are talking about race, talking about gender. Younger people now are so much more aware. The word inclusion has come out of this era, the idea of including everyone. I’m not romantic about it. But I’m looking at what’s coming from young people and it’s awesome.