“I feel compelled to talk publicly about it,” Askini said, noting that everyone who has approached her recently seems to have the same questions about her disability.

For an outspoken activist like Askini, who currently serves as the executive director for the Gender Justice League, the adjustment to her new life has been profound. Today, the 35-year-old — blonde highlights, bright, gummy smile — finds herself not only advocating for those in the LGBTQ community but for those who are disabled as well. Askini says she sees parallels between the discrimination she faces as someone who is transgender and the challenges she and others with disabilities must overcome.

“It’s really fascinating how invisible I feel in this new way,” Askini said. “I feel like I walk into rooms, and people don’t even see that I’m there. Maybe because I’m usually so vocal.”

“It feels somewhat eugenicist,” Askini continued. “Like only perfect people get to have ideas or contribute to our culture and thinking. Only people who are perfect can know how to solve social problems, especially ones they haven’t experienced themselves.”

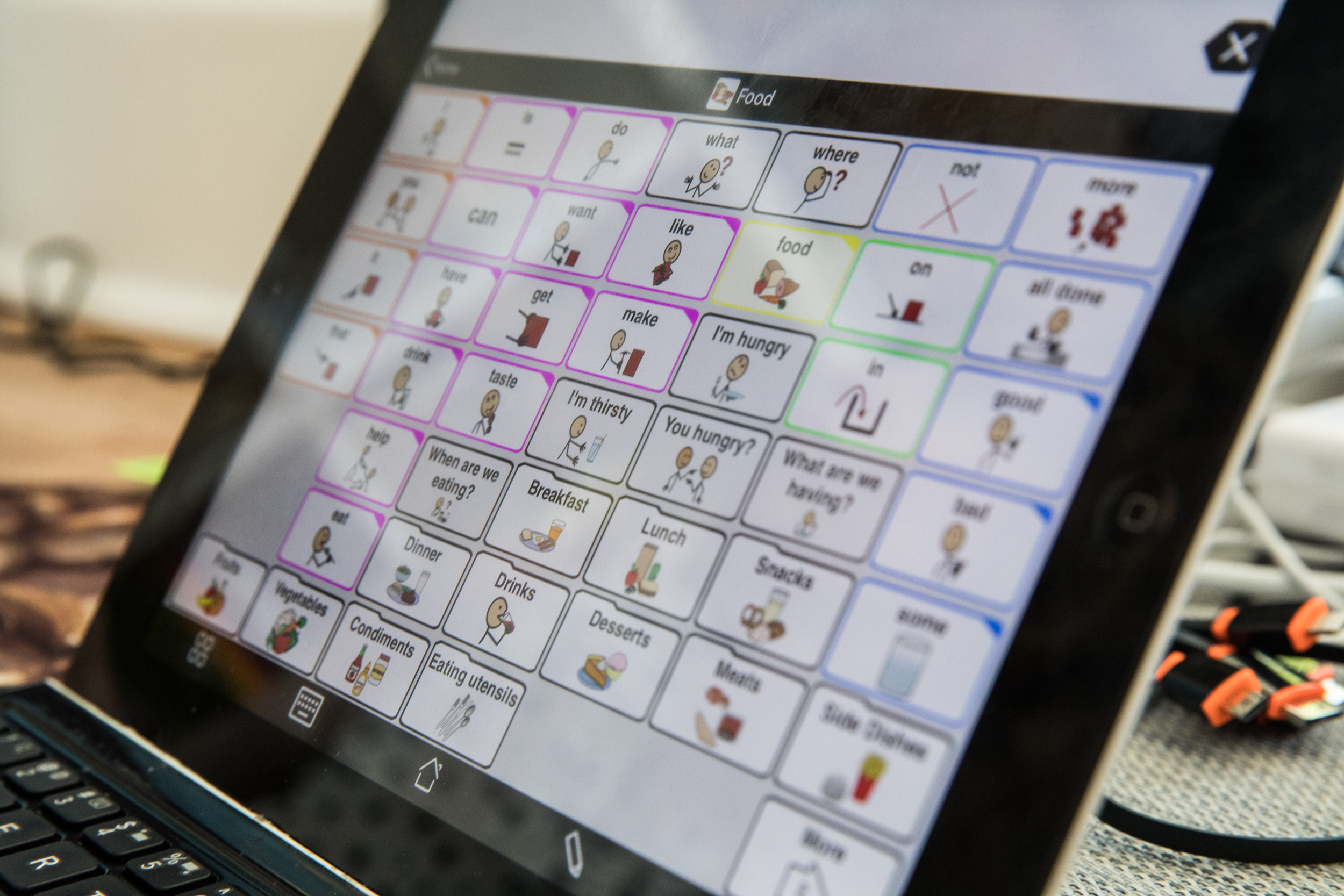

“I’m just as brilliant, funny, hardworking and knowledgeable. But I need to use technology to communicate.”

Although Askini is coping well, her disarming sense of humor and accompanying wisecracks fully intact, she admits the learning curve for her disability has been steep. In the four weeks she has been mute, Askini has already learned how to sign more than 100 words, including phrases that might come in handy at the office, such as asking for names.

She has also collected a handful of horror stories about ableism or the belief, as she puts it, that people with disabilities are inferior to others. She freely shares many of them on Facebook.

For example, there were the construction workers at Kaiser Permanente in Capitol Hill who spotted Askini using sign language with her instructor and mistakenly assumed she was not only mute but deaf. They proceeded to talk about Askini as if she wasn’t there, joking about the “waste of a nice rack.”

“They thought it was hysterical. If I end up in jail, you’ll know why,” Askini joked.

In another Facebook post, Askini described a recent doctor’s visit:

Scene: Speech Pathologist Office Waiting Room

Dude: "Hey, are you here to see Dr. M?"

Me: *pointing to my mouth and shaking my head* *mouthing* "I'm Mute"

Dude: (excitedly) "Omg, you're gorgeous AND mute?! You're every man's dream woman. Finally, a woman who can't talk back. *self amused chuckle* "Are you married? Please say no."

Most recently, Askini wrote about going to the movies. As a result of her surgery, Askini’s right ear has a tendency to fill up with water and needs to be periodically drained. Slightly hard of hearing, Askini planned to use a closed-captioning device so that she could fully enjoy the movie. She belatedly discovered, however, that the device would only work in the theater’s accessible seating row. After Askini and her partner sat down, a man yelled at them for taking his seat, despite attempting to explain her predicament and although most of the theater remained empty.

Yet Askini believes most “people are not being malicious or unkind. We just don’t know what we don’t know.” Askini also says most of the accommodations she asks people around her to make are relatively minor, like simply slowing down.

“I think I’m learning that people are unnecessarily fast in their day-to-day life,” Askini said. “Everyone rushes through conversations. There is a consistent feeling that I’m bothering and annoying people.”

“Oftentimes the conversation moves way beyond me, and I’m talking about things people were talking about a minute ago. So it feels disruptive and annoying to the group consciousness because I’m interjecting in a non-sequitur way.”

There’s also an awkwardness Askini encounters with certain people, which is not unlike the thorny situations she’s had to navigate as someone who is transgender.

Often they apologize, but Askini points out “sorry” isn’t really helpful: “I am fine with being a person who can’t talk… If you are having feelings about this please process it with someone other than me.”

“A more helpful way to express solidarity,” Askini wrote on a tip sheet for those attempting to communicate with her, “is to tell me how great I am at adapting, that you’re happy to have me around.”

Askini, who is Jewish, grew up in a suburb just outside Portland, Maine. She says when she first began to transition in high school, approximately 20 years ago, her family was supportive, even if they didn’t always understand. Unfortunately, Askini couldn’t count on others in the small conservative town to be as compassionate. In high school, she grew out her hair, and was bullied and harassed as a result, even surviving several serious hate crimes, like being threatened with a knife and hit by a car.

“People knew I was assigned male at birth so it was a big deal,” Askini said. “I had a huge target on my back.”

Askini learned early on from her mother, who battled mental health issues, and her grandmother, a union organizer and mill worker for 45 years, how to advocate for the underdog. Still, Askini eventually found herself living on the street — homeless. After about a year, Askini, then 16, entered foster care. Two gay men — queer youth group advisors — took her in; she describes them as “hardasses” and “amazing.”

Askini moved to the Pacific Northwest after attending undergrad and graduate school in social work and nonprofit management at the University of Maine. After helping run a transgender health care program on Capitol Hill, she left Seattle briefly for San Francisco where she worked for the Gay Straight Alliance Network. In 2010, she married and lived in Sweden for a year.

But after receiving a devastating diagnosis, her marriage fell apart. Doctors diagnosed Askini with a rare and potentially fatal blood disorder called Aplastic anemia.

“I had a lot of feelings then about having my partner watch me die at age 30,” she said.

In the end, Askini was saved by a bone marrow transplant. Her previous health battles, however, continue to put her current condition in perspective.

“I don’t have my voice back, but I still am healthy. I can do almost everything I want to do. I can get out of bed, exercise, work. So I think my perspective is a little bit different than everyone around me who think this is the worst-case scenario. At least I can still communicate,” she said. “All things considered, I thought I was going to die at 30. This feels like a rather minor outcome.”

After surviving the bone marrow transplant, Askini escaped an abusive relationship and set her sights on running for political office. In 2016, Askini ran for an open state House seat in the 43rd District. She dropped out to focus on fighting I-1515 — a ballot measure that sought to restrict bathroom access for transgender people.

Today she and others at the Gender Justice League are concentrating on ensuring trans people have access to the healthcare they need.

Askini continues her work even as she faces multiple surgeries — possibly two this week — in an attempt to regain her voice. On Thursday, she will remain awake for a six-hour surgery as doctors strive to tighten one vocal cord that loosened after the tumor was removed.

Askini estimates she's already spent $15,000 on medical procedures. She has zero savings as a result.

Although she is hopeful, to be safe, Askini is planning for the worst. She’s taking sign-language classes. She has half-a-dozen buttons ready to wear that explain her condition: "I am mute"; "Please speak directly to me"; "I am mute...but I can hear you."

She's also as busy as she's ever been, preparing for next month's Trans Pride Seattle. This week, as she and her staff continued to prep for the annual march and rally, Askini carried her iPad around with her in the office. Always ready to laugh, Askini pointed out that with a quick tap of the screen, Siri could vocalize her coffee drink of choice. (Iced coffee with soy milk and sugar, or cold brew.)

Then, just like that, Askini and the entire team set back to work, determined to speak out for those in the transgender community who are not always heard.