The project is a joint effort between King County and the City of Seattle and is the first “mega-project” Seattle Public Utilities has ever undertaken. Seattle will be on the hook for about $95 million of the cost increase, with the County picking up the rest.

In 2014, officials estimated it would cost the city and county $423 million, with Seattle absorbing 65 percent of the costs and the county paying for the rest. From the beginning, the project has driven up customer bills, which are slated to go up next year by about 8 percent for single family homes and nearly 9 percent for apartments. But in an interview Tuesday, Project Executive Keith Ward with Seattle Public Utilities said the higher project cost will not push utility bills higher.

Seattle has long struggled with nasty overflows into the ship canal, Lake Union and Lake Washington. The current tunnels combine rainwater and sewage, diverting the two at a fork in the pipe. The system works fine in dry conditions, but in the wet months, the tunnels are less effective, leading to overruns.

It all came to a head with a 2013 consent decree between the city, the state and the federal government to dramatically reduce sewage and wastewater runoff into Seattle area waters.

Last year the city had more than 130 overruns along the ship canal, spilling about 90 million gallons of a sewage and rainwater sludge into the city’s waters. From Lake Union to the Ballard locks in particular, testing showed significantly higher e-coli levels immediately after a runoff.

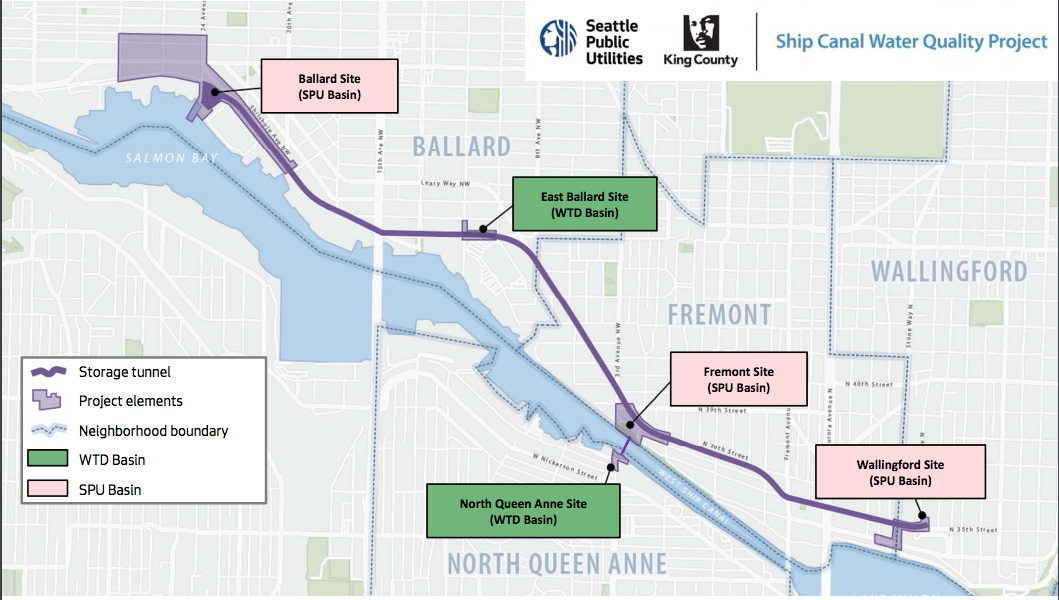

Under the agreement with the federal government, by 2025 the city and county must reduce that number near the ship canal to just six runoffs per year, down to 8.5 million gallons. The more expensive Ship Canal Water Quality Project, a nearly 19 foot wide tunnel that will run along the ship canal, is by far the largest piece to reducing spills.

Part of the department’s explanation for the cost increase should sound familiar: $39 million is the result of increased property values and labor costs. Utility and transportation departments across the region are struggling with similar challenges in the booming economy. Sound Transit recently blamed a $500 million increase to its Lynnwood line on higher property prices.

But the department also increased the diameter of the tunnel by nearly 5 feet last year, in anticipation of heavy rainfall that could come as a result of climate change. That increased volume added another $25 million to the price tag. Ward said there was no way past teams could have controlled for increased rainfall. “Climate change science is changing,” he said.

But Ward also said early teams were more confident in their estimates than they should have been. In 2014, the project was still very early in its design plans, which makes predicting final cost very difficult.

SPU’s current director, Mami Hara, took over the department in 2016. When she noticed ballooning costs, she ordered a 9-month pause on the project between summer 2016 and May 2017. In the meantime, she brought in outside experts to do a more thorough cost analysis.

Madeline Goddard, Deputy Director of the SPU’s Drainage and Wastewater Branch, said the changes were necessary and appreciated. “There was a reason we had a change in leadership. I’m going to say we’re human. We have a really capable team. The project was driven more toward getting the project done without looking at the impact it had to the rates.”

Officials gave themselves some cushion at the start, budgeting enough to avoid more customer rate increases even if the project exceeded its original $423 million estimate. The newest number exceeds what was budgeted originally, but Ward said he believes the department can cover the gap — around $30 million — via state grants and favorable interest rates to avoid more rate hikes.

Going forward, SPU will have to present its final design plans and cost to the city council before it can proceed with tunnel construction. The department will also be required to provide semi-annual progress reports.