It is no secret that Seattle is rapidly changing. When I moved to Seattle in 2004 the city was already changing, but somehow, I found myself in the loving arms of Black communities that have played an important role in making this place what it is now: home.

A Place Where We Tell Our Story

A house is a place where you live. A home is a place where you love, and love is exactly what greets me as I walk into the Northwest African American Museum. A group of geese is called a gaggle. What do you call a group of Black aunties laughing and chit-chatting with arms wide open? A pride? Yes, like a pride of lionesses they are there at the entrance of the museum giving out hugs, big smiles and stern looks as only wisdom can. It takes me at least ten minutes to move ten feet from the door to the front desk before LaNesha DeBardelaben, the museum director, is alerted that I am here for a meeting

The museum director doesn’t mind that I am now late because as she comes out to greet me, she too is embraced by the pride of aunties. We make our way back to her office for our interview. DeBardelaben explains it is mid-winter break and some of the museum staff have brought their children to work. “It takes a village,” she says.

The Northwest African American Museum, known as the NAAM, sits on Southwest Massachusetts street in the historically red-lined Central District. It occupies the historic Colman School, built in 1909, the first to admit Black students and the first to hire Black teachers. NAAM is the only museum in the Northwest dedicated to telling the stories of Black peoples.

It took a lot of work to launch the museum, going all the way back to 1981 when the Community Exchange, a multi-racial coalition, proposed the creation of an African-American museum. The mayor at the time, Charles Royer, was supportive, but by 1985 when the school closed there had been no significant movement.

The impending expansion of I-90 threatened to erase an important piece of Seattle’s Black history. As a result, activists entered the building through a broken window and occupied it, demanding the building be preserved as an African-American museum. The occupation, led by Omari Tahir Garrett, Mona Bailey, Esther Mumford, Ann Gerber, P. Razz Garrison and Janice Cate, lasted 8 years — one of the longest demonstrations of civil disobedience in the United States. In 1993, the city agreed to fund the museum but it was another 10 years before Seattle’s Urban League purchased the building for $800,000 from the Seattle Public Schools District. On March 8, 2008, the Northwest African American Museum opened as part of a complex containing both the museum and 36 affordable apartment units.

Now a decade old, the museum is a labor of love and a reflection of the struggles faced by Black communities in Seattle. “[It] has a very purposeful history,” DeBardelaben says. “NAAM came to be out of pressure, like a diamond.”

NAAM opened the year I graduated from college. To be honest, I wasn’t as excited about it as I should’ve been. Maybe it is because I did not yet see young black womxn like myself — a fairly militant Black mixed queer womxn born in the 80s — as a part of the museum’s story. Despite feeling disconnected, I continued to visit the museum. In 2016 Tariqa Waters’ exhibit, "100% Kanekalon: The Untold Story of the Marginalized Matriarch," changed everything for me.

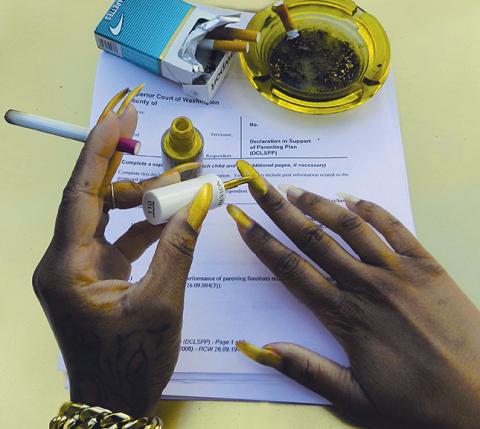

Waters’ exhibit brought the story of so many womxn I know into a space where we should have always been but had not yet been welcomed. Her exhibit brilliantly told the stories of the marginalized matriarch, making space in the museum for our strength, character and wisdom without judgement. We do not often talk about the issue of class in the Black community, about womxn who do not fit the mold of respectability but whose lives are an important part of caring for and nurturing our communities. Waters’ work opened the door to a new wave, a more holistic and unapologetic wave, of Black art and storytelling in the museum.

NAAM is moving towards a more holistic approach in its programming, offering fitness and wellness classes, dance parties and community conversations (they have hosted Crunk Feminist Collective, which offers a “space of support and camaraderie for hip-hop generation feminists of color, queer and straight”). The current exhibit, “Everyday Black,” an exhibition of work by Jessica Rycheal and Zorn B. Taylor, is a captivating invitation into the many faces of Blackness. And with the addition of a new exhibit, Power to the People, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Seattle Black Panther Party, I will be sure to visit the museum a few more times before both exhibits end.

There are only three African American museums in the United States that are nationally accredited, and DeBardelaben wants NAAM to be the fourth. Her goal is for NAAM to be “a fully accredited museum that is at the highest level of educational excellence, exhibitions and programs — that are relevant and empowering, that are interactive, dynamic, and deeply rooted in community.” The director envisions a museum that “is present helping to improve the quality of life of people, especially African Americans in Seattle.” Telling our stories unapologetically and honestly is one of the most powerful things we can do. NAAM, working with local artists, is evolving and expanding how we do this.

A Place Where We Dream Together

Across the city, under the domed Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, an old home is being restored. “This place [Langston] has been a home to many generations of the next generation of Black artists in Seattle,” says Tim Lennon, executive director of LANGSTON, a new non-profit housed in the building whose mission is “cultivating and showcasing Black brilliance.”

My first memory of the performing arts institute is the Teen Summer Musical — a Seattle tradition since 1989. I can’t remember the first production I saw, but I remember how I felt. It was like coming home from college for Christmas — all of my family gathered together laughing and talking as the smell of greens and fried chicken (yes, my family makes chicken for Christmas) filled the house. I came to the show because I knew at least 10 youth in the production and left knowing at least 10 more, plus their families. Music, like home and Christmas, brings peoples together. LHPAI is a place where we come together to be at home through music and art.

Built in 1915, originally the Jewish Synagogue of Chevra Biku Cholim, LHPAI has always been home to artists, faith congregations and community groups. While it has served many communities, central to its purpose has been its connection and commitment to the African Diaspora. Yet as gentrification pushes many Black Seattleites out of the Central District, an historically red-lined neighborhood, LHPAI remains.

LHPAI has had many names, but those most familiar simply call it, “Langston.” The building is named after Harlem renaissance luminary Langston Hughes, who first spoke in Seattle on May 26, 1932. Even then Seattle was known to be more progressive than the rest of the United States, but even then people had their critiques. In 1946 Hughes, invited to speak by the Associated Women Students of the University of Washington, said, “Negroes all over America are under the impression that Seattle understands them, although there is not too much opportunity for them here.”

Throughout the United States, Black people are being forced out of their homes at an alarming rate. Seattle is no different. Lennon views his nonprofit as an opportunity to “leverage the moment and ... find some national strategies for investing in Black arts organizations.” Black churches, schools and arts organizations have always been staples in Black communities, spaces that have created a much-needed refuge from the struggles faced by Black peoples living in the United States. Even more, arts organizations, like LANGSTON and the Teen Summer Musical, provide a positive reflection of Black creativity, identity, resilience and ingenuity.

Yet how does one build a liberated space for showcasing and cultivating Black brilliance in a predominantly White city? My own experience as a performing artist in Seattle has taught me to prepare for predominantly White audiences who are not always prepared to receive all of my work. If I am honest, there are times I do not feel free to perform the work I want to without feeling consumed as a product and not received as an artist. Lennon believes that by curating a space that aims to explicitly cultivate Black art and Black artists we can challenge Seattle to move from simply consuming to investing in Black arts and artists.

“A home is a place where you dream,” Lennon says. So LANGSTON, Lennon hopes, will be a place “where we can collectively dream up our new reality.” A place “... where we feel safe, comfortable, welcomed and empowered enough to envision what freedom looks like for us right now.” As a forced exodus of Black residents continues, Lennon imagines LHPAI staying fiercely put. He says, “This building will not be easy to move.”

A Place for Our Peoples

Black peoples in Seattle are not a monolith and not all Black spaces serve the needs of all Black Seattleites. Yet there are places like LEMS Life Enrichment Bookstore, lovingly referred to as LEMS (pronounced li-m-s), where you will find Black churchgoers, Black youth, Black millennials, Afrocentric Black folks, Hotep Black folks, Black academics, Black artists, Black elders and Black revolutionaries all in one space being two things: very Black and very proud.

There is no place in the city like LEMS, a longtime South End staple that has lived in many different locations — but always on Rainier Avenue. LEMS settled in its sixth location on Rainier nestled on the edge of Columbia City and Hillman City in 2008. It straddles two South Seattles: the gentrified part and the one seemingly untouched.

LEMS was founded by Ms. Vickie Williams more than 20 years ago. Ms. Vickie, a treasured community auntie who deeply loved people and books, died at the age of 65 on March 3, 2017. The service celebrating her legacy was attended by well over 1,000 people. The legacy of the bookstore lives on through her partner Aaliyah Messiah and Messiah’s son, Hassan. Its operation is a labor of love by community members who host numerous programs and activities.

The bookstore has evolved over the years. Ms. Vickie originally opened it as a Christian bookstore. Over time, as Ms. Vickie and the neighborhood changed, LEMS transitioned from just being a bookstore to a cultural hub and bookstore for the Black community. It’s “a pillar in the Black Seattle community,” Jerrell Davis, a local musical artist and activist, said after hosting his album release party recently at LEMS. “Beyond that the legacy of its founder Ms. Vickie Williams is iconic. LEMS has always been a consistent part of my life and Ms. Vickie a beloved auntie.”

While the bookstore is marked with a sign, you’ve got to know someone who knows someone to know if it is open on any given day. And once inside, if you are not an insider you might find yourself confused by the eclectic array of materials and objects in the space. Amid the sage smoke, kente cloth and Egyptian sarcophagus there are shelves of books with everything from Jet magazine to Ptahhotep to homeschool materials for Black educators and families. It is a space that deeply reflects the African diaspora and the struggle of Black peoples — stolen, brought to the United States, stripped of culture and spiritual practices — to reclaim and re-root ourselves in our identities.

Every event I’ve ever attended at LEMS starts with the pouring of libations. Libations are the way we remember who has come before us and how we invite them into our spaces. Our ancestors, shared stories and practices are the foundation that binds us; our bond is the vision for a brighter future.

In December, the bookstore hosts Kwanzaa — the longest running Kwanzaa celebration in the Pacific Northwest. For seven days LEMS becomes a center of culture and activity leading up to the new year. No matter what I have going on I try to stop by as many nights as possible. The laughter, the food, the zeal of the youth, the wisdom of elders and the pride of aunties reminds us how important it is that we remain connected to each other and our culture. Kwanzaa is a time to reaffirm our commitment to community and the importance of thriving together.

LEMS may not be as flashy as Langston or NAAM, but it is a space whose story, location and very structure deeply reflect the current challenge of Black peoples struggling to live in Seattle. The push out is real. Gentrification is more than a buzzword to make hipsters and tech bros uncomfortable. We are watching our homes disappear.

And when that disappearance happens, when it starts to feel like the city doesn’t want us, it’s essential we have spaces where we can live in the fullness of our humanity. Spaces that do not treat Black peoples as a monolith or a hot-button issue for election season. Places where we are safe, nurtured and welcomed. Places we can be at home because after all there is no place like home.