Yes. And Exhibit A is An Octoroon, an audacious blend of melodrama, social critique and in-your-face lampoonery that is the latest reason to check out ArtsWest Playhouse.

ArtsWest is presenting the Puget Sound premiere of this free-wheeling, Obie Award-winning script by Black East Coast playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. The show is just the latest theatrical stimulant the small-scaled but increasingly attention-grabbing West Seattle company has offered recently.

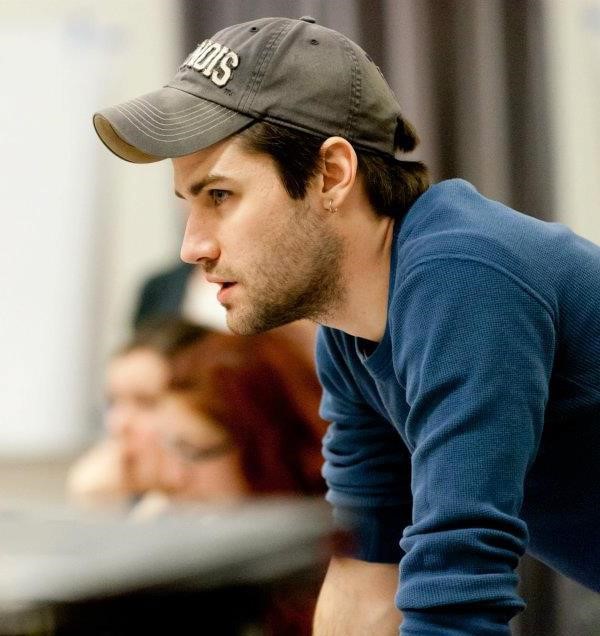

“I want to give the audience something they can’t get at home watching Netflix,” declares ArtsWest artistic head Mathew Wright. Over the last couple of years, Wright, along with managing director Laura Lee, has been evolving ArtsWest from a long-running, quasi-professional outfit into a go-to venue that presents well-tooled versions of buzzed-about new musicals and dramas and, on occasion, invigorated stagings of still-vital classics like Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman and Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts.

Since joining ArtsWest in 2014, Wright has been laser-focused on upgrading the company’s production values with more detailed and ingenious sets. He has recruited and hired some of Seattle’s most in-demand performers, directors and designers for their first West Seattle gigs. And he’s putting more racial and cultural diversity onstage than ever.

This season those missions have resulted, in part, in mounting an intriguing play about generational, gender and religious conflict in a Muslim-American clan (Ayad Akhtar’s The Who and the What); an update of Shakespeare’s Macbeth focusing on affirmative action and the ruthless academic ambitions of a pair of Korean-American twins (Jihae Park’s Peerless); and producing a sleek and intimate version of Stephen Sondheim’s grim musical fable Sweeney Todd starring Filipino American powerhouse Ben Gonio in the lead. Now it’s tackling An Octoroon, a rambunctious play-within-a-play that’s been with some acuity described as “Gone with the Wind-meets-Loony Tunes.”

Wright, a savvy thirty-something who arrived at ArtsWest after stints as a 5th Avenue Theatre staffer and as a director and musician in Philadelphia’s theater scene, likes to say that his goals at ArtsWest are “all about people.” That is, hiring the best people available in Seattle’s generous theatrical talent pool to do “what they do best” and making sure his audiences connect with the fare ArtsWest serves up.

But, of course, there’s more to it than that. Wright inherited from the late Christopher Zinovitch, ArtsWest Playhouse’s artistic director from 2000 to 2012, a penchant for scoring local rights to hot new theatrical properties before larger and better-known Seattle theaters get their mitts on them. (For instance, Zinovitch mounted the acclaimed I Am My Own Wife in the 149-theater theater in 2008 — four years before the much larger Seattle Repertory Theatre presented it.)

However, Wright is clearly taking ArtsWest (which was created in the late 1990s by local arts leaders and former members of Totem Theatre, a local community drama group) to the next level: creatively and financially. Season subscriptions have doubled during Wright’s tenure. Single tickets are also on the uptick. Meanwhile, the company’s operating budget has climbed from $881,000 in Wright’s first season, to about $1.2 million for 2017-18 — with very few full-time employers running the place.

In addition to adding more pizazz and polish to his productions, Wright also endeavors to incite “more conversation with the audience” — the kind that’s spurred on by plays that get people gabbing. The theater hosts post-show response sessions after every performance.

Those chats will likely be very lively during the run of An Octoroon, a play Wright secured, he says, because “it’s one of the hardest-hitting commentaries on the history of race in America that I’ve ever seen.” (It runs at ArtsWest through May 13.)

Introduced and at times narrated by a character based on the playwright Jacobs-Jenkins (played here by the versatile Lamar Legend), An Octoroon filches the broad outlines of the 1859 Dion Boucicault melodrama The Octoroon and riffs off of boldly exaggerated Old South stereotypes of Black slaves and White plantation gentry that still feed into our national images of race, geography and cultural difference.

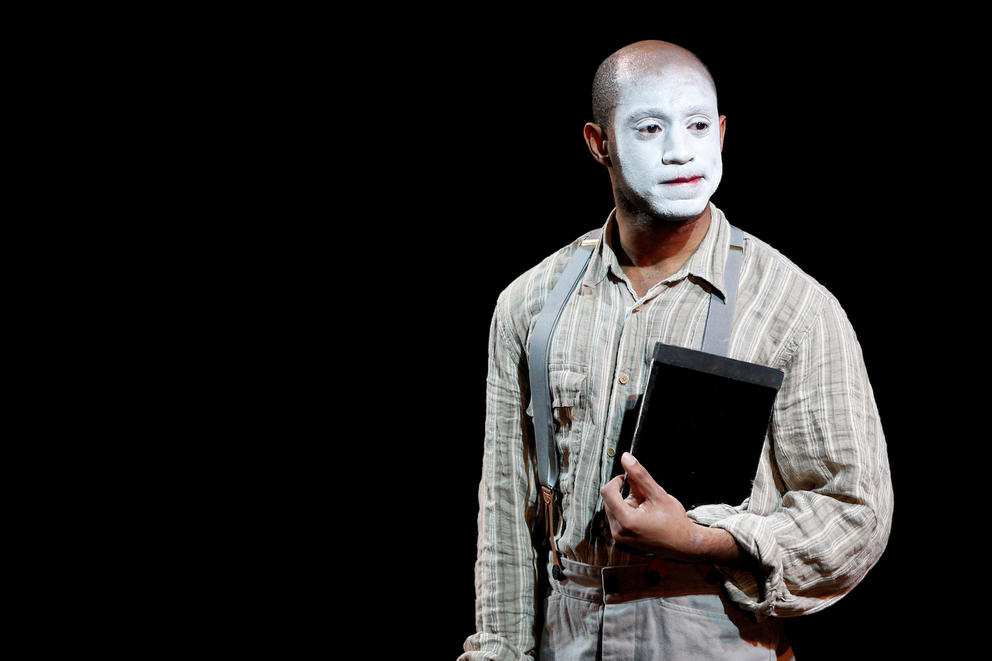

But in this weepy tale of a young woman (Zoe, played by Jessi Little), who is identified as an “octoroon” (an archaic, now-offensive term for someone “one-eighth black” by descent), and the White suitor who loves her but can never wed her because of her “tragic mulatto” (mixed race) status, Jacobs-Jenkins has turned the racial landscape topsy-turvy. A White actor (Mike Dooly) plays a fierce Native American in scarlet-red facial makeup. A Black actor (Legend) dons whiteface to portray plantation heir George, Zoe’s high-born beloved. And at ArtsWest, an Asian American performer (Jose Abaoag) wears blackface as Uncle Pete, the show’s buffoonish surrogate for a kind of “Uncle Tom” slave figure whose drawling, shuffling presence on stage (and film) lasted well into the 20th century.

Meanwhile, as you are laughing uneasily at these caricatures, a trio of female Black slaves (portrayed by Dedra D. Woods, Jéhan Òsanyìn and Jazmyne Waters) tell it like it is in “typical” profane, modern Black urban slang, layering cliché upon cliché.

There’s even a cameo appearance by Br’er Rabbit, a wily trickster bunny who may have originated in African legend but is best known from the 1946 Disney film Song of the South — which, as the NAACP put it, “helped to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery.”

An Octoroon throws a lot in your lap, including some painful images of racial violence that has not yet been vanquished. You are left to sort out what’s funny or tragic, meaningful or offensive, or all the above. Directed with care by Brandon J. Simmons, on opening night the show hadn’t yet cranked up a whirlwind tempo the sprawling five-act opus needs. But it has likely picked up speed since then. And the sheer ambition of the effort, and the cast’s versatility and stamina, are laudable, as is the chutzpah of ArtsWest for taking it on.

Sure, another daring theater in Seattle could have tackled An Octoroon. But Wright and company got there first. And productions like this make ArtsWest an increasingly attractive option for those who like their theater adventurous, vivid and demanding — even if it means crossing the busy West Seattle Bridge. Not that Wright considers his theater’s location — in the heart of the revitalized downtown Junction district with its array of restaurants, bars and hundreds of new apartment units and, if you get there at the right time, free parking — a hindrance.

“It’s not some sleepy, suburban community,” he asserts. Culturally speaking, ArtsWest may be one of the reasons why.