There was a time when Congress worked. It was a time when many of issues that confront us today – renewable energy over fossil fuels, voter access made easier, and caution about broadcast media monopolies – were being addressed. And there were few more skillful practitioners than the late U.S. Rep. Al Swift, the Bellingham Democrat who served 1979 to 1995.

Swift, who died April 20 at 82, passed the nation’s most progressive energy legislation (in 1980, no less) made registering to vote as easy as getting a driver’s license, and jawboned the broadcast networks into hitting the pause button on prematurely declaring presidential winners.

Despite his progressive record of success, Swift was something of a political enigma. When he ran in 1978, he was the long-shot outsider against a more establishment Democrat. But he was no stranger to Capitol Hill. He served twice as the top aide to one-time Congressman Lloyd Meeds, and he was student of the operating style of a legendary legislative insider from Washington state, U.S. Sen. Warren Magnuson.

He wasn’t the highest profile politician and he left office before many Washingtonians arrived on the scene. But the lessons about making government work for people that we could learn from Swift seem both relevant and all the more important in these days of division, partisan gridlock and anger from almost all sides. Swift held a liberal sensibility, but he wasn’t a table pounder or protest leader.

Instead, Swift was a legislative craftsman. In his first term, as the Pacific Northwest lurched toward a multi-billion-dollar financial debacle over plans to build a network of nuclear power plants in the state, Swift guided legislation through the House that set unprecedented progressive energy policy that treated conservation as an actual energy resource. His legislation also effectively spelled the end to large-scale nukes. You can, in part, thank Swift for why the Northwest has some of the greenest, renewable-focused utilities in the nation today.

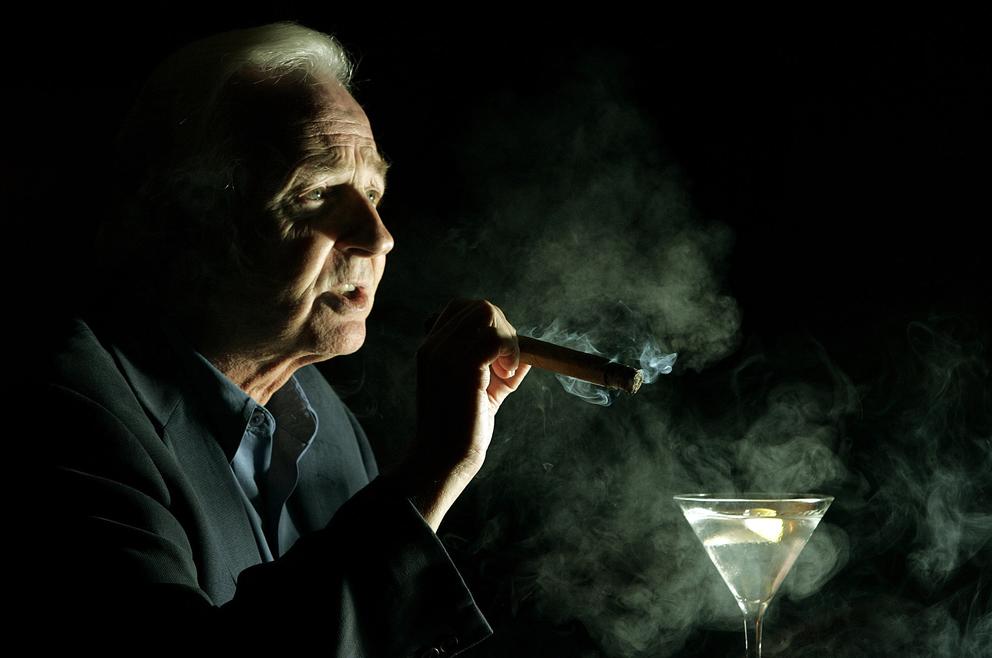

I covered Swift in that 1978 campaign for the Seattle Times, then went to work for him in Washington, D.C., and later wrote about him when I returned to journalism. Over the years, he was a mentor, a friend and someone who helped shape my notion of public service (although not quite the same fondness for “exceedingly dry martinis” and cigars).

In 1980, as Swift watched President Jimmy Carter concede on national TV at just after 5 p.m. PST, discouraging West Coast voters who, in some cases, walked away from the polling places. Oregon Democratic U.S. Rep. Al Ullman, chair the House Ways and Means Committee, went down to a flaming, ignominious defeat. Swift used his position on the House Commerce Committee to persuade the networks to refrain from early reporting of East Coast exit polls and calling presidential races nationally minutes after polls closed there.

At the same time, striking off in a very different direction than today’s efforts at voter suppression, Swift was determined to make it significantly easier to register to vote, so he passed the so-called motor voter law registering every citizen who got a driver’s license.

Al fundamentally believed solutions often came from compromise. It was not a dirty word. It was the coin of the legislative realm. “Look, we tend to over-legislate those things we don’t trust or understand,” Swift once offered. “Liberals don’t trust the military or business, so we regulate the hell out of them. Conservatives don’t trust social programs and public projects, so they regulate the hell of them. And sometimes neither approach makes sense.”

Swift, a former broadcaster, took such an approach to reforming the Communications Act of 1934. He favored opening competition in the burgeoning telecom sector, which today has brought cellular service to virtually all sectors of the country. But he was a skeptic of media monopolies such as you see today with right-tilting broadcasting buccaneer Sinclair. Swift wanted to modernize the dated act, but he was worried of putting too much media power in the hands of a few corporations. His concern is vividly borne out today as we see wholesale media consolidation and the loss of local ownership.

Even in his pre-Internet era, Swift had a sage take that applies across the political spectrum even today. “Dare not ascribe to conspiracy,” he offered, “that for which mere stupidity shall suffice.” It was vintage Al Swift, but also somehow timeless.

To some, especially the very liberal circles of Bellingham, Swift was somehow not very liberal. When Mike Lowry, who entered Congress with Swift in 1978, would wave his arms and denounce the Reagan Administration Swift seemed too moderate, too measured, too middle-of-the-road. There was an irony to that perception.

Shortly after Lowry lost his 1988 U.S. Senate bid against Republican Slade Gorton, I was talking to one of Gorton’s closest adviser, eventual Safeco CEO Mike McGavick. Ever the shrewd operator, McGavick was bemoaning that my old boss Swift had ruined a great TV they had planned against Lowry. They had carefully scripted a 30-second TV spot, attacking Lowry as the most liberal member of the state’s congressional delegation. But they ran into a problem, McGavick confided. After scouring ratings from labor, business and other groups, the Seattle congressman wasn’t the most liberal.

It was the guy from Bellingham, Al Swift.

Swift’s rhetoric was never red hot. Like his smooth baritone voice, he was politically soothing. He worked effortlessly with Republican Joel Pritchard, a similar legislative craftsman, in rounding up votes for regional common good. There developed mutual respect between Swift and Gorton, despite they seldom voted alike.

By 1994 and the rise of Newt Gingrich, Al made the decision to retire. He saw Gingrich as a partisan warrior who cared little about policy or driving towards solutions. Swift shied away from political sexy issues of the moment; he took a longer view that in retrospect today was both visionary and prescient.

Swift, unlike some lawmakers, didn’t live for the power, the title or the corner office although by the time he retired he had all those. Occasionally, when he might get a little full of himself, his late wife Paula would quickly deflate him. “Yes, Allan (she would call him by his full name at times like this), it is terrible that the voters made you run for this office.” Al would cast a sheepish look over his glasses and say, “Alright, let’s go get a martini.”

No matter their station, Swift innately understood people wanted to be heard. And by listening, he could look for things they had in common. From years anchoring a KVOS-TV public affairs show in Bellingham, he knew how to draw people out and guide the conversation. And from there came compromise and solutions — all driven by a man of uncommon common sense.

We could all learn that lesson from Al Swift.