She deals with these problems with a combination of surging anger and delightfully scorched-earth skepticism, especially when it comes to MS support groups. She emphatically is not ready to belong to “the society of victims and sufferers.” (When told that she’s supposed to be resting, she snaps back, “Doing nothing makes me tense.”)

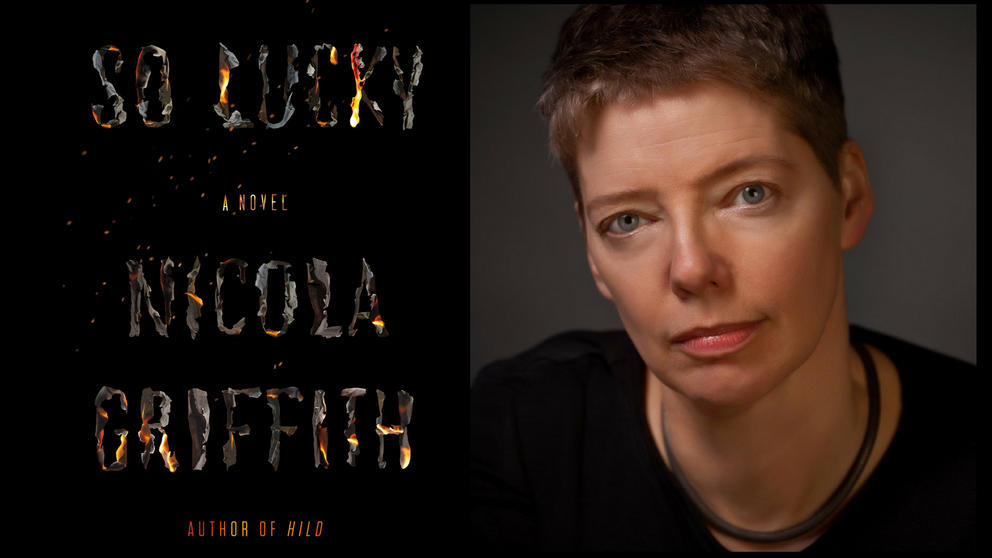

Griffith, 57, is best known for her novels featuring lesbian PI Aud Torvingen (Stay, The Blue Place, Always) and for her 7th-century-set historical novel Hild, which won the 2014 Washington State Book Award. Griffith’s other honors include the Nebula Award, James Tiptree Jr. Award and six Lambda Literary Awards.

She lives on a quiet cul-de-sac in North Seattle with her wife, writer Kelley Eskridge. She has had multiple sclerosis for 30-odd years, but this is her first book to take on MS so frankly. In person, she’s more soft-spoken than you might expect, but direct in all she says and quick to laugh. So Lucky is, by her own account, like nothing she’s done before. This is an edited version of our conversation.

In your acknowledgments you write, “No one – not even me – knew I was going to write this book.” What’s that saying, and where’s that coming from?

In 2016, I was writing the sequel to Hild — Menewood. And I was about 60,000 words in when I got the opportunity to do a Ph.D. at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. And it was an amazing opportunity, so I decided I would do that. I’m sure there are some people – but I’m not one of them – who can write an all-involving novel set in the 7th century and do a Ph.D. at the same time. So, I put my novel aside.

I worked on the Ph.D. for a few months, wrote the first draft of my thesis, sent it off to my advisor in the U.K, then had this three-week period where I didn’t really want to go back to the novel. I’d been working really hard for a long time, the engine was still running, and I didn’t know where to turn it. I sat down and this stuff came roaring out. Just pouring, ripping, gushing. High-velocity firehose kind of thing. Two and a half weeks later, I had the first draft.

Once you learned that your editor at Farrar, Straus & Giroux was up for publishing it, you wanted it to come out quickly. Why was that?

In the first draft, there was a lot of stuff about healthcare. And politically a lot was going on with healthcare at that time. So, it felt really of the moment. I was also aware that by the time it was published it wouldn’t be of the moment, and I had a feeling I was going to rewrite that part anyway. But still, the feeling was there. The main thing was representation. There are so few good books out there with disabled protagonists. Most of them are written by non-disabled writers, and they are pitiful – sort of the disabled equivalent of the way queer lit was 70 years ago or 100 years ago. People sacrifice themselves. They are broken and sad and pitiful. And I’m tired of that.

Mara is fiercely straightforward but almost comically unaware at times of her intimidating effect on other people.

Yeah, it’s one of her flaws. She thinks she sees everything so clearly. And of course, she doesn’t. Nobody does. And it was weirdly freeing to write her. She just does things and says things, convinced of her own righteousness and she doesn’t always have a clue how she’s landing. And, of course, she was the head of this massive organization, and she thought that she was totally understanding and knew everything and was really clear-minded about everything. And then she finds out, the first day she’s diagnosed, that she hasn’t really thought about that and clearly she’s not very good at this. And then there’s her temper. So, we begin to see her. As she realizes her physical vulnerability, I think readers see more and more her actual flaws as well. They’re deeply entwined.

The book reads as though you have hands-on experience with the kind of organization that Mara runs. But I don’t see that in your bio.

In the U.K. many years ago I worked at a nonprofit agency for helping people who had drug dependencies. We helped people get on methadone programs. And we did smoking cessation and we did alcohol counseling. I was a caseworker. I would help people figure stuff out. I saw a very small version of this and could extrapolate from that. But I also helped form a couple of non-profits, too. Then, of course, a lot of people I knew were involved with HIV work. I thought: Logically, where would this go if you were head of that kind of agency and used to moving in those circles?

You clearly draw on your own medical experience as you get into the nitty-gritty of Mara’s shock at her diagnosis. She has a weeks-long numb phase — and then she kicks into action. Was that what it was like for you when you were diagnosed with MS?

Yes and no. In many ways, this book is not like my experience. In one year, Mara figures out what five years of being sick and more than 25 years now of being diagnosed has taught me. So, she is on an accelerated learning program. And MS was very different when I was diagnosed in 1993. There were no immunomodulatory therapies at all. There was nothing. In fact, a few months after I was diagnosed, one drug came on the market and it was so rare, so scarce, that there was an actual lottery for it. Basically, back in the day, you were diagnosed with MS and it was like: “Ah, well, good luck with that.”

Any other differences between your and Mara’s experiences?

Yes. I just want to be really clear, in case any of my neurologists and healthcare providers read this: The neurologist in this book is nothing like any neurologist I’ve ever had. The neurologists I’ve had have been really good. And my physical therapist is nothing like the physical therapist in this book, either.

You mentioned that the first draft had a lot more explicit stuff on medical care. You wrote this in early 2017, so just at the time when the Republicans and Trump were doing their best to swing a sledgehammer at Obamacare.

It was terrifying. But it became clear, even as I was finishing my Ph.D., even before I got back to the rewrite, that we didn’t know, topically, how things were going to go. And you know publishing is such a drawn-out process that even though this was on an accelerated publishing schedule, it was still not going to be out until some things had already happened. So I decided to take that back a bit. There was a lot more in there also about MS itself and how it works and the politics of how it’s funded. And again I just thought: “Oh, this is just tedious. I don’t need to be hammering on this stuff. It’s not what the story is really about. I can write an essay one day if I want to.”

So Lucky eventually incorporates a crime-driven subplot, which surprised me because I was so deeply invested in the situation-driven, character-driven parts of the book. Did the idea for the crime story come late in the writing of the book? Or was it there from the start?

It was always there. Actually, the first inklings of this book happened many years ago, not too long after I was diagnosed, when I heard a news report about a guy in a wheelchair who’d been tortured and murdered. That’s what set off the train of connecting personal vulnerability to group-identity vulnerability and what it’s like to actually be victimized. That’s what Mara does for a little while. She immediately goes to the completely vulnerable place: I’m a victim. People like me are being victimized. And the fact is a lot of people are victimized and you just have to figure it out. You just have to find a way to cope.

The book is peppered with remarks on how Mara’s physical situation affects her perceptions. There’s a line where she remarks: “The airport looked different from a wheelchair.” It’s a fresh, searing experience for her — but I’m guessing that for you, because you’ve been living with MS for so long, these are situations you’ve become used to handling.

Well, it’s different for me now. I don’t get put in a wheelchair at the airport anymore. I use my own, and I’m in charge of it. But I remember that first time in a wheelchair. It was just like that. That, I think, is probably the most autobiographical line within the book: the wheelchair, and just being treated like a sack of potatoes. They say to people, “Is she okay? Does she want…?” It was like: “Hello?” And they literally don’t hear you. They don’t see you. You’re not real. You’re not a real person. It’s a very difficult thing to get past. I’m no longer shocked by it, so it’s just easier to either shrug it off or deal with it properly now. But at the time I was just like: “Really? Did that just happen?”

There’s another line Mara has when she’s wondering how frank to be about her MS: “I’ve been out all my life. I’m not going back in, not about anything.” For you, does the book itself take your being candid about your multiple sclerosis to a different level? Is it like coming out again?

I’ve been out my whole life. To me, I felt as though I was born with “dyke” stamped on my forehead. I never had any worries about that. And I’ve never hidden my physical impairments. But I’ve only just, in the last couple of years, kind of come out as a “cripple” in the sense of claimed the identity as “disabled” as opposed to someone with MS. It’s a slightly different thing. I really do see disability as a social issue. It’s not a medical problem. It’s not about my impairment. It’s about the cultural and built environment. I am disabled because I don’t have access to things. My impairments don’t make me disabled. They make me impaired. The disability is how society discriminates against me and other disabled people.

Any trepidations about tackling this subject in fiction?

I’ve only just come across this phrase but it’s perfect — I’m having “rep sweats” about it. I’m sweating about having to represent everybody, being responsible for carrying some kind of kind of banner for disabled people or, more particularly, people with MS. I foolishly hadn’t expected that. I’m just waiting to see what happens.

If you go: Nicola Griffith will be reading at Seattle's Phinney Books on May 15, Seattle's Elliott Bay Book Co. on May 16 and Bainbridge Island's Eagle Harbor Book Co. on June 7.