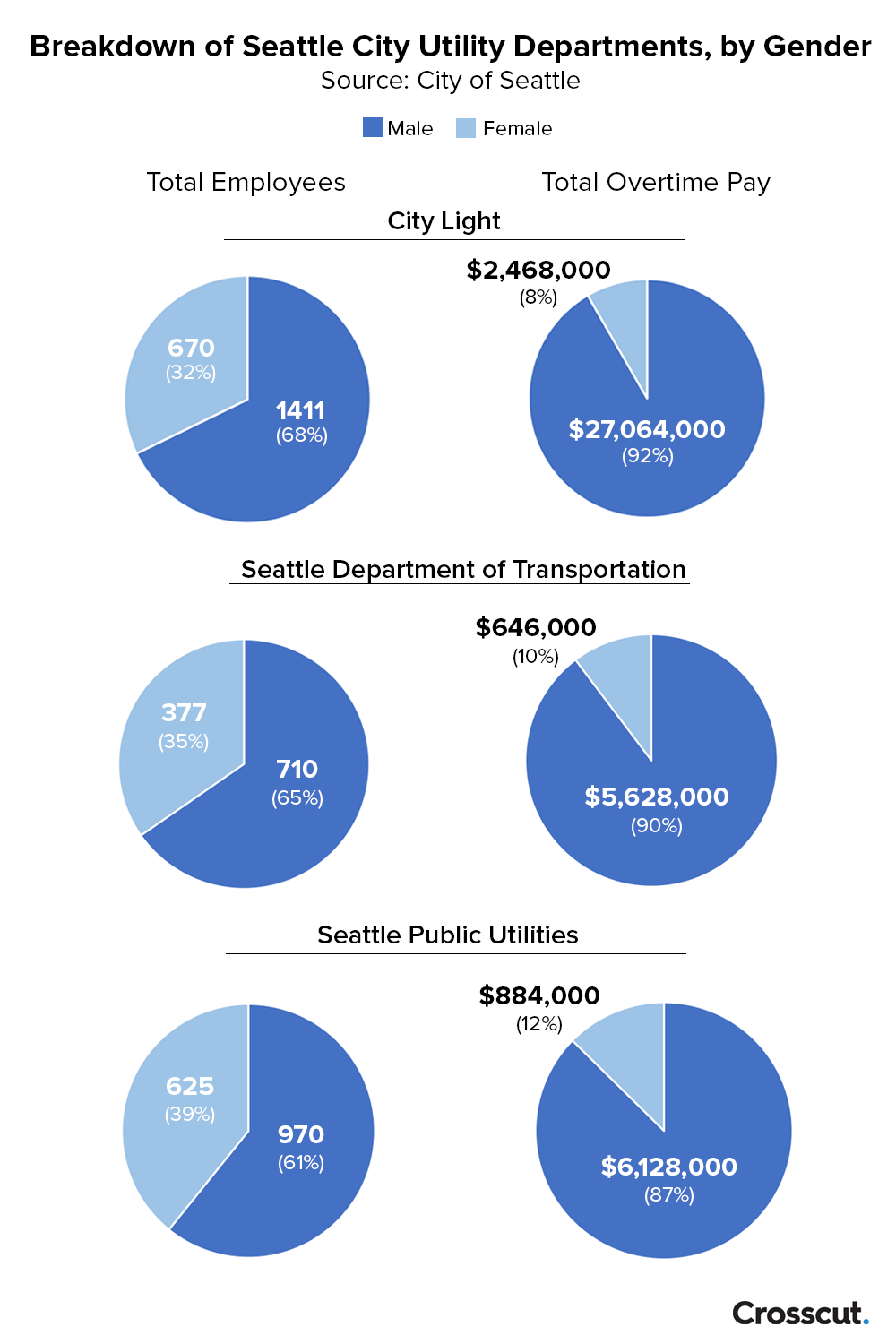

In real terms, where men across three of the city's largest departments — Transportation, Public Utilities and City Light — brought home about $39 million in extra pay last year, women earned just $4 million. That's despite the fact that women on average were hired to work nearly the same number of regular hours per year.

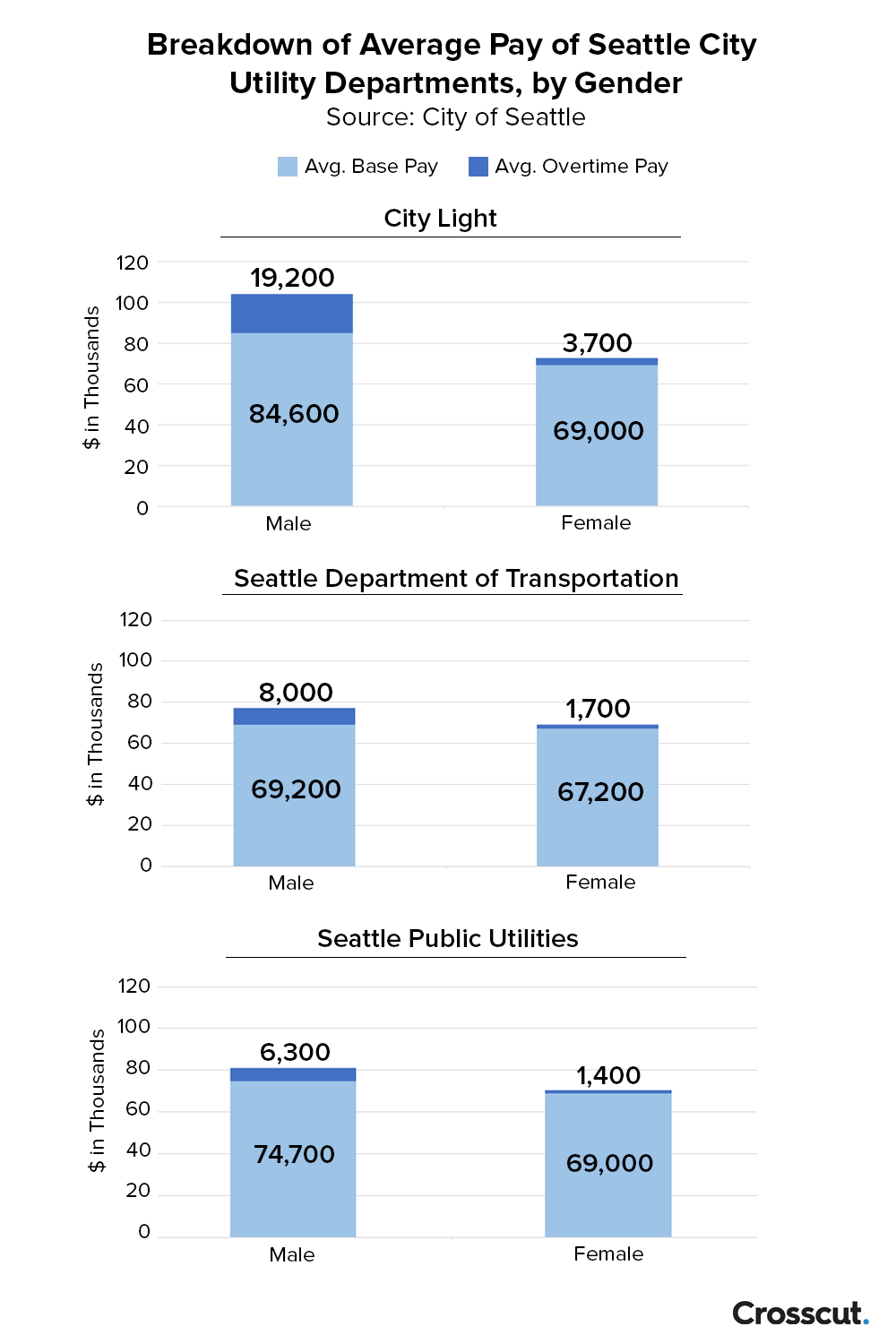

It's a disparity that drags down the pay ratio between men and women in that corner of City Hall by more than 10 points: Where women's base salaries before overtime equate to 90 percent of men's, their gross salaries, including overtime, dip to below 78 percent.

At an individual level, men in the transportation and utility departments increased their salaries through overtime by an average of $12,571, while women increased theirs by only $2,385, or just 19 cents to the dollar.

This disproportionality is a sharp departure from a relatively rosy 2015 analysis, which found women who work for the city made nearly 90 cents to the dollar. At the time, former Mayor Ed Murray bragged that the results show Seattle “outperforms the region and the rest of the nation.”

But the city did not include overtime pay in its analysis, casting a shadow on the results of that report.

“We would have seen a much bigger pay gap if we’d seen that data,” said Barbara Reskin, Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the University of Washington and a member of the city’s Pay Equity Task force that helped to carry out the research.

Overtime disparities are especially pronounced in the utilities and transportation departments, where men overwhelmingly hold positions more likely to earn the extra pay.

Already, the Seattle Department of Transportation, Seattle City Light and Seattle Public Utilities represent $3 billion of the city’s total $5.6 billion budget. As Seattle infrastructure explodes with its population, the departments have relied on overtime to keep pace. In 2017, they dolled out $43 million for extra hours, with City Light accounting for nearly $30 million of that.

Twenty-one employees made more than $100,000 in overtime alone and workers routinely doubled their annual salary through working extra hours.

Crosscut has not received data for the city as a whole. But the effect of the overtime disparity in other corners of the city is not likely to be as pronounced as it is in utilities and transportation because most departments, with the exception of Police and Fire, do not rely so heavily on overtime.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Seattle Public Utilities, Andy Ryan, pointed to work the department is doing with apprenticeship programs and recruitment. "We recognize that we have work to do to continue building a diverse and inclusive workforce," Ryan said in an email. "SPU is committed to providing employment opportunities for women and people of color, including in positions that have historically been occupied by men."

City Light's Administrative Services Officer DaVonna Johnson, echoed this sentiment. "We continue to work hard to recruit more women and minorities to these well-paying jobs," she said in an email. "Among recent efforts are: Participation in the Women in Trades Fair; ANEW (Apprenticeship and Non-traditional Employment for Women) pre-apprenticeship program; Vocational/community college outreach; Hosted tours; Veteran job fairs."

The overtime drag on pay equity is not just a Seattle issue. In fact, it may account for why the rapid narrowing of the gap over several decades has stalled in recent years.

In 1960, women made just 60 cents to the dollar. By 2004, that number had climbed to 77 cents. But in the subsequent years, that progress has slowed. In a recent study from PayScale, women are likely to earn 78 cents to the dollar in 2018.

In a 2014 paper published in the American Sociological Review, researchers suggested that the gap has not closed more quickly in part because of “overwork” — 50 hours or more in a week. “Because a greater proportion of men engage in overwork, these changes raised men’s wages relative to women’s and exacerbated the gender wage gap by an estimated 10 percent of the total wage gap,” wrote authors Youngjoo Cha and Kim A. Weeden.

In Seattle, cable splicers, line workers and electrical workers in Seattle City Light earn the most overtime, often responding to power outages and racing to get new construction on the grid. One cable splicer, Michael Yi, earned over $203,000 in overtime, nearly tripling his annual salary.

As it happens, these positions are dominated by men. Of 78 cable splicers, only nine are women; of 142 line workers, only ten are women.

SCL's Johnson said, across the department, 7.5 percent of "skilled trade" jobs are women, which she said is higher than other publicly owned utilities. "Skilled trades positions at Seattle City Light tend to have the most opportunities for overtime and are among the highest paid hourly workers at the utility," she said.

It's a similar dynamic in SPU: According to the spokesperson Ryan, "Service/Maintenance and Skilled Craft categories tend to work the most overtime. Employees in these categories have significantly higher percentages of men than women."

The gender disparity in overtime-friendly jobs illustrates how the wage gap is less often the result of blatant discrimination and more commonly because of systemic biases and preconceived ideas about men’s work versus women’s work.

“I’m not saying it’s on purpose, but this kind of culture just favors who’s there first,” said UW Professor Reskin in an interview. “In our society it’s men who were in those jobs first and it’s very hard to get those jobs integrated. . . . And then when that culture is somehow also labeled as masculine or feminine, there’s resistance [to integration]. Because the people who already have it want to preserve it for members of their group.”

In the 2015 study referenced by Murray, a consultant could not find any evidence of explicit gender bias or discrimination among Seattle employees holding the same jobs. It also could not find significant disparities in hirings or promotions. Side by side, men and women in the same positions earned almost the same amount.

The 10-cent disparity Seattle did find stemmed largely from unequal distribution of labor in more lucrative jobs. In response, the city pledged to examine recruitment and hiring practices, among other steps.

Similar forces are also at play when it comes to overtime. But Reskin said the task force wasn’t given that information to include as part of their 2015 analysis. “I don’t know what was going on then,” she said, acknowledging that overtime disparity is an important part of the larger picture.

Additionally, although the 2015 report did not find any explicit biases in promotion, there is discrepancy in which utility and transportation employees get “out of class” assignments — temporary placements in jobs above an employee’s pay grade.

Out of class assignments are “supposed to give people opportunities for future promotions because they’re getting experience,” said Denise Krownbell, a City Light employee and President of PTE Local 17. “And it helps the city because it gets them cross trained.”

The temporary increase in pay can also help pensions later.

But of 1,335 out of class assignments in City Light, Transportation and Public Utilities, 1,030 went to men, which means only 23 percent of the assignments went to women. It is unclear how many women applied for out of class placements.

For Reskin, these disparities get at a larger question of how biases work. “The greater the decision makers' latitude in deciding who gets any special deals such as overtime the more likely they will give them to . . . people whom they see as like them,” she said. Whether it’s intentional or not is, to a certain degree, beside the point.

She added, “This boils down to whether there are criteria for determining who gets overtime and how much they get [and] whether those criteria can be justified and are actually used in allocating overtime.”

And as Crosscut has reported, employees in SDOT — particularly women — have gone on record with concerns that favoritism within the city is real. One employee with SDOT, who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation, accused her department of using both overtime and out of class assignments as an avenue for showing this favoritism.

“Both [overtime] and [out of class] provide paths by which SDOT management can give raises to anybody they please without having to go through a monitored hiring and wage-setting process, without scrutiny,” this person said. “[Overtime] and [out of class], then, are both methods of meting out favoritism and arbitrary pay raises, mainly to men."