Update, April 16: Arthur Longworth has been reinstated in his college program.

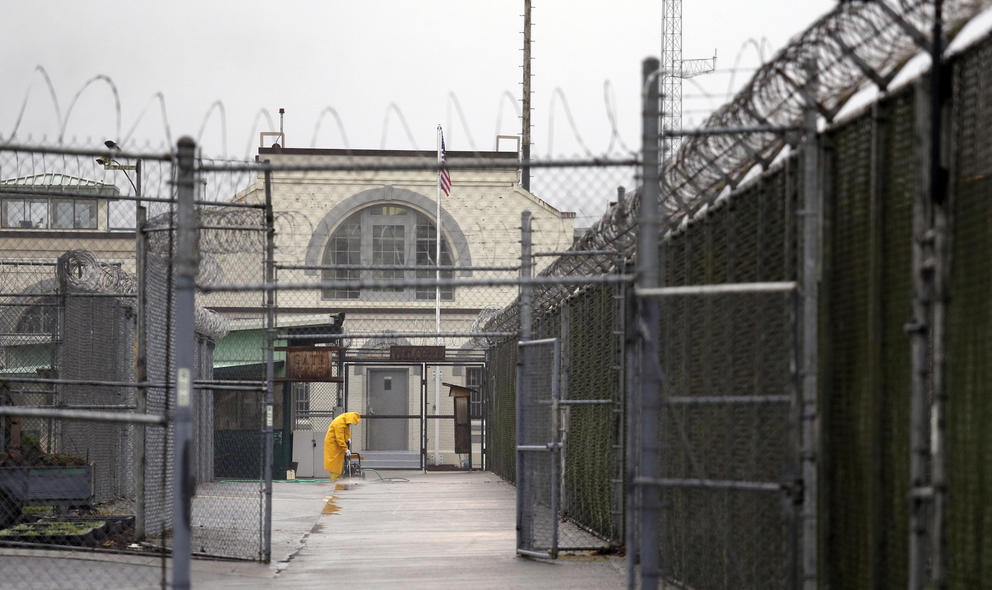

After more than three decades in the Washington state prison system, where he is serving life without parole for aggravated murder, Arthur Longworth can stake a legitimate claim to being a writer. In 2016, from his cell at the Monroe Correctional Complex just outside Seattle, he managed to publish a 186-page novel that earned positive reviews and is available on Amazon and at bookshops around the country.

His prose has been read onstage by novelist Junot Díaz. He is a multiple winner of the PEN America prison writing award. He is also a contributing writer for The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization that covers the U.S. criminal justice system.

But he is still incarcerated for the 1985 killing of Cynthia Nelson. And this month, in the latest battle over the disputed territory of prisoners’ First Amendment rights, Longworth says he is being punished for behaving like a free man.

A spokesman for the Washington Department of Corrections acknowledged that Longworth was suspended from his paid job as the law-library clerk at Monroe, removed from all of the college courses he was taking through the University Beyond Bars, a nonprofit prison higher-education program, and blocked from submitting an essay about life as an incarcerated writer to The Marshall Project.

Spokesman Jeremy Barclay said the reason for Longworth’s removal from the programs he’d attended for years was not his publishing efforts but rather a Feb. 22 infraction he was found responsible for, “lying to staff.”

Longworth, who spoke to The Marshall Project on an email app called JPay, says he was initially given no explanation for his dismissal, other than an “administrative decision.” Although the alleged incident occurred in February, he was not notified of the infraction until March 29 — the day after a reporter asked why he was being punished.

On another occasion, the DOC confirmed, Longworth was informed that his outside communication was denied for “writing an article with no approval from superintendent.”

Some of the great literature of western civilization was written by authors who were imprisoned. Thoreau, Wilde and Cervantes all wrote from incarceration. So did Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King, Jr., whose “Letter from Birmingham Jail” has found new audiences this month on the fiftieth anniversary of his murder. But the extent to which prison inmates in the United States enjoy the protection of the First Amendment has never been precisely defined in the courts.

In 1987, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Turner v. Safley that “prison walls do not form a barrier separating inmates from the protections of the Constitution,” but also that speech can be limited if there are “legitimate penological concerns” at stake. The result of that blurred legal standard is that, in practice, staff at any given prison have great leeway to limit inmates’ privileges — both reading and writing — by citing security concerns or the potential for disruption.

“Censorship is the reality of the prison system,” David L. Hudson Jr., a constitutional expert at the First Amendment Center, told The Marshall Project in 2016, when Longworth’s book was banned. “The Supreme Court pays lip service to prisoners’ free speech but has not been very protective.”

As a result, Hudson said, what’s allowed and what’s not varies widely by state and even by prison. (See The Marshall Project’s quiz: “Do You Have What it Takes to Be a Prison Censor?”)

In Washington state, written materials can be rejected for not being in English; for appearing to be in code; for advocating the “overthrow of authority”; or for depicting the geography of the Pacific Northwest or otherwise being plausibly useful in an escape.

Washington, like many states, forbids criminals from profiting from accounts of their crimes, but that does not seem to apply to writing on other subjects, such as conditions in prison.

Four other inmates at the Monroe prison and two volunteer staff there corroborated Longworth’s account of being removed from all of his classes and programs, though no one said they could be sure of the DOC’s exact motivations.

Longworth said the infraction stated that he told a guard he needed to leave work early to make a phone call to a family member. “I don’t even have a family… They’re not even good liars,” he said.

“The truth is,” he added, “prison officials are angry because I wrote a book that they regard as unflattering to them.”

Longworth’s novel, “Zek,” which is Russian slang for a forced-labor camp inmate, does make criticisms of prison violence and of the behavior of corrections officials. But it is in the style of literary fiction, and is based in part on events from many years ago at a different Washington penitentiary.

DOC officials said the book was a security risk because it describes such tricks of confinement as where to hide tattooing paraphernalia and techniques for transferring contraband.

Marc Barrington, a former volunteer writing teacher who smuggled a hard-copy manuscript of Longworth’s novel out of the prison in 2016 to get it published, was banned from the facility for “undue familiarity” with a prisoner. “It has been reported that you have assisted an offender at the Monroe Correctional Complex with publication of the offender’s book,” his suspension notice read.

The DOC then filed a state ethics complaint against Barrington, accusing him of assisting an offender in a transaction that resulted in financial gain. He was cleared of that charge.

Any prisoner who possesses a copy of Longworth’s novel will be sanctioned, including possibly by having their release date postponed, inmates said.

The DOC declined to comment on this allegation.

Michael Moore, a prisoner at Monroe, said that he too recently tried to write and publish a book — by sending out 53 emails of 6,000 characters each on JPay. A couple of days after he did so, he said, he received a notice saying his mail was being censored.

“To be honest,” Longworth said, “I don't understand what bothers them about my writing or why they go to extremes to punish me for what I’ve written, as well as do all they can to prevent me from writing more. When I look at my writing, it seems to be merely an attempt to convey the experience of long-term incarceration.”

This story was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow The Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.