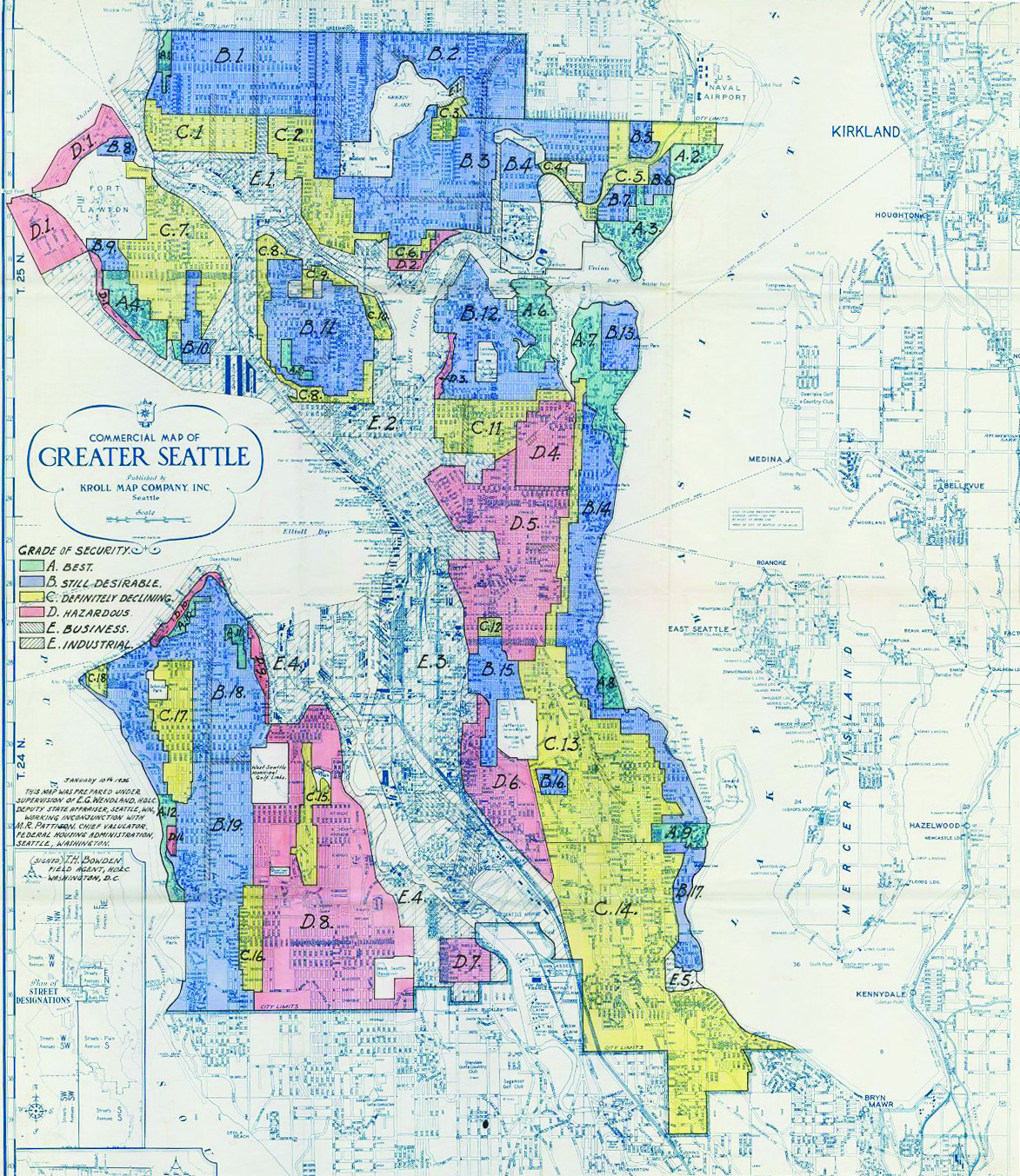

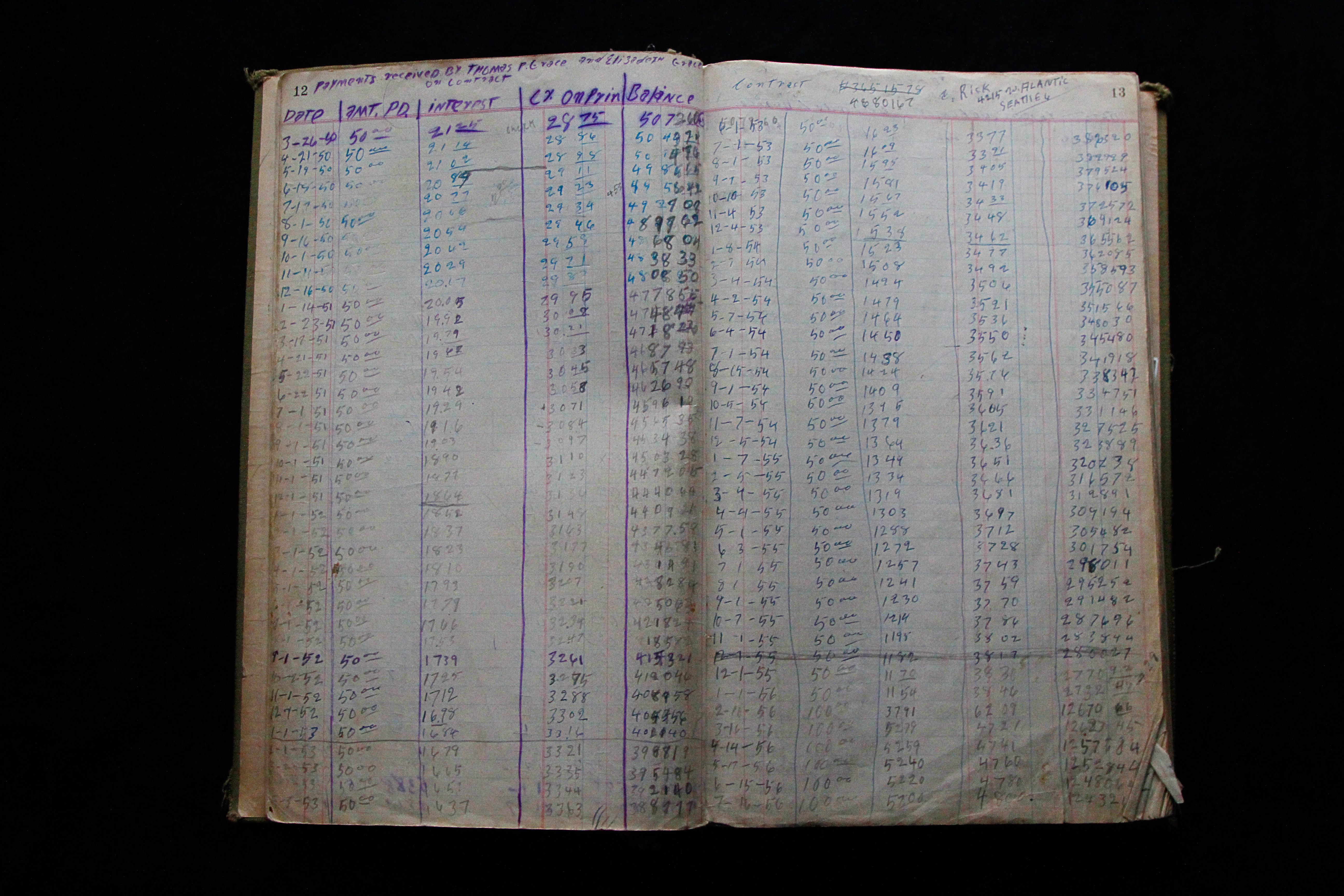

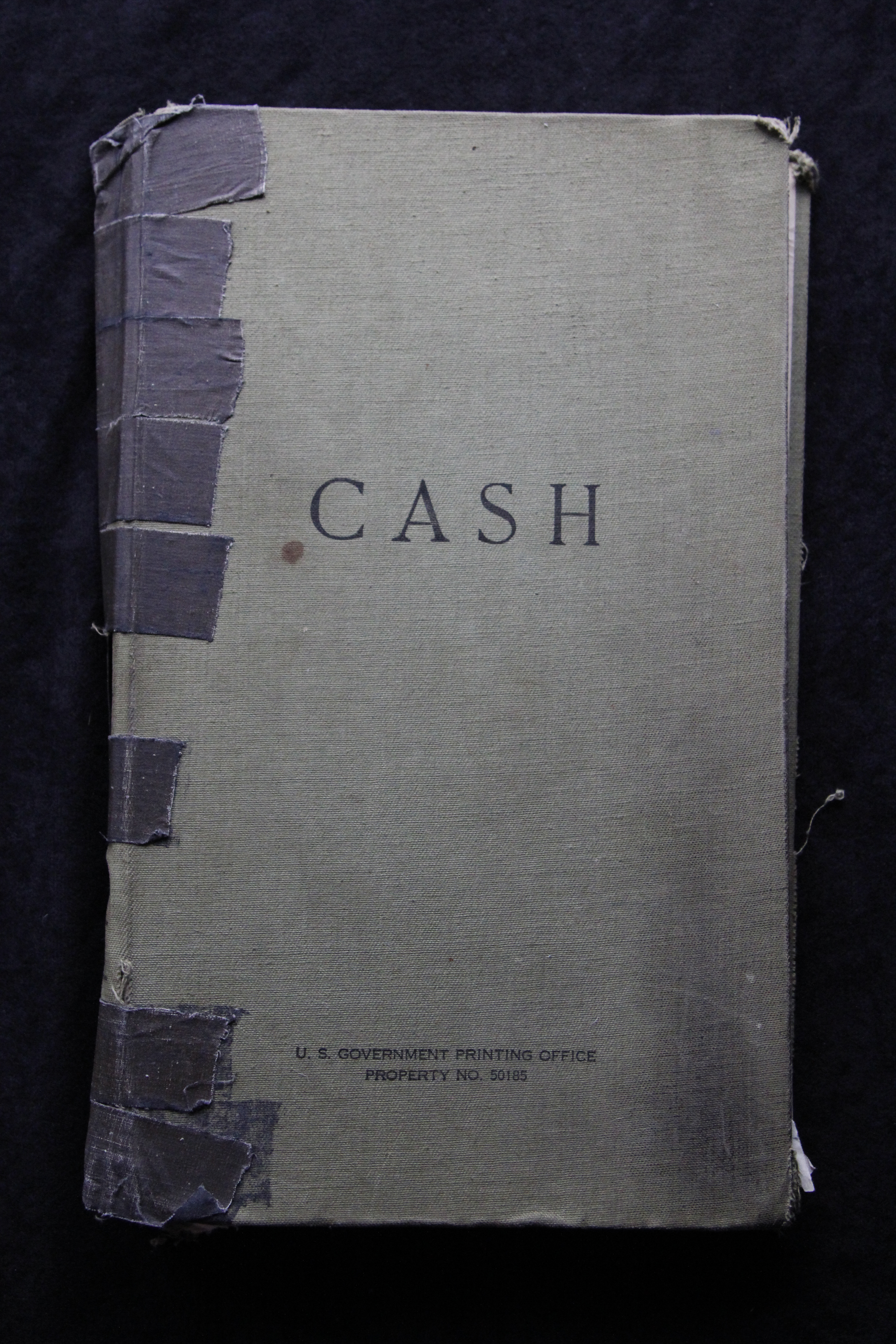

He purchased a duplex at 913–915 24th Avenue, overcoming barriers to homeownership for African-Americans — which included redlining — by buying the house directly from the White owners, Thomas and Elizabeth Grace. (Redlining is the practice of banks literally coloring in red a map of areas with predominantly Black populations and declaring those neighborhoods “hazardous,” and either barring home loans or making their interest rates untenably high.) In 1951, he bought another home from the Graces located next door to the first house, keeping track of his monthly payments in a neat ledger that spanned decades. Today, this house is owned by Green’s grandson Inye Wokoma, who grew up in the Central District (CD), surrounded by numerous family members in a community that was walkable and intergenerational.

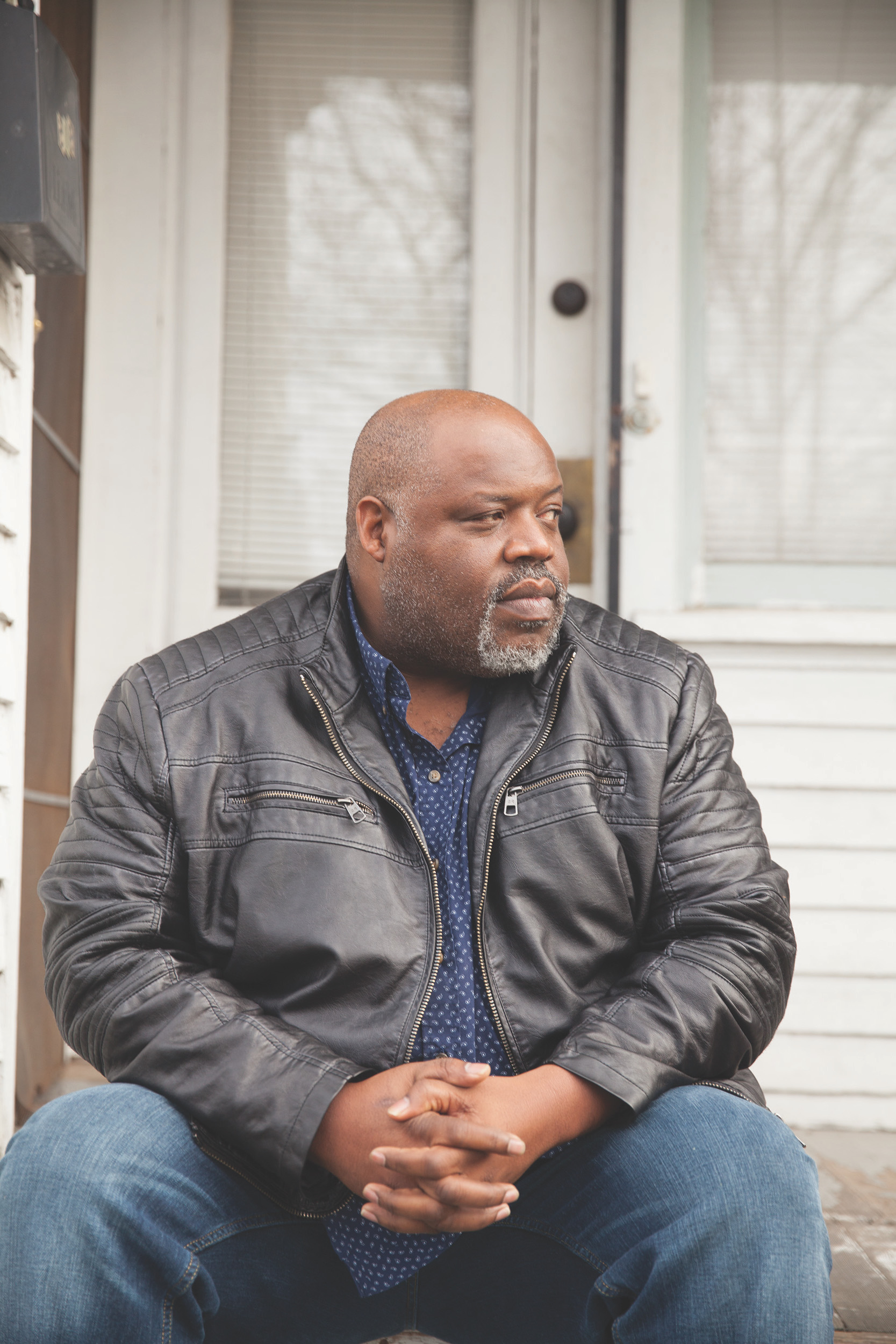

Now 49, Wokoma is a filmmaker, photographer and visual artist, one of 11 siblings and father of three. Wokoma, a tall, soft-spoken man, is the manifestation of the saying “Still waters run deep.” A consummate intellectual, he’s quick to laugh, but speaks with purpose, power and passion, each thought the culmination of years of careful deliberation, analysis and reflection.

Over the past two years, Wokoma’s family history has been the subject of his two solo museum shows, This is Who We Are at the Frye Art Museum in 2016 and An Elegant Utility at the Northwest African American Museum in 2017. Both shows explored his family’s relationship to place, home and community, together with his family’s and larger African-American community’s decades-long battle to retain a foothold in the Central District against the forces of displacement.

Change will happen, but Wokoma wonders whether there’s a way for a city to change without upending a community. “The Central District is a place whose geography is familiar, but whose people and features are increasingly strange and unrelated to who I am,” he wrote in An Elegant Utility. “Being here makes me wonder how can we re-imagine and design communities in ways that don’t erase what is already alive and present? What values are central to our imagination as we do this? How can we draw on the best human-centered traditions and imagine new cities where even the most vulnerable among us can thrive?”

The story of Green and Wokoma, of course, begins much earlier than 1947. It can be traced to 1865, when slavery ended — an event that only marginally improved life for African-Americans in the South. Sharecropping, segregation, ever-present threats of violence, no voting rights and ruthless, criminalizing “Black Codes” worked together to ensure that the African-American population remained economically and politically subjugated.

Life for Franklin Green and his family in Perry, Arkansas, was difficult. Their work as sharecroppers, domestic workers and livestock farmers in rural Arkansas was brutal, and the pay did not provide enough to keep food on the table. Green and his family knew there would be no opportunity to improve their lives if they stayed in the South, where violence was omnipresent and not an abstraction. When Green’s mother was a child, her parents worked through their church for greater social and political rights for African-Americans. One night, they left their four children at home to attend church, and while they were away, the house was firebombed by a mob of Whites. Two of the children died; his mother and uncle survived. The terrorism would haunt the family for generations.

So, like 5 million other African-Americans between 1915 and 1960, Green became part of the Great Migration and joined his sister, Betty Green, to start a new life in Seattle. When the migration began, 90 percent of African-Americans lived in the South. By the end, 47 percent lived in the North and West. Frank and Betty were just the first two of eight siblings to make the migration; five of the siblings settled in Seattle with the family matriarch, Mariah Wert-Green.

Drawn by the promise of better job prospects, less racial violence and greater educational opportunities, families like the Greens took a huge gamble on the unknown. Yet life in the Northwest was no utopia. Alarmed by the influx of thousands of African-Americans to their cities, Northern Whites created a multitude of obstacles to mobility. Cities created “sundown” laws that prevented blacks from being outside after dark; the constitution of Oregon explicitly barred African-Americans from entering the state until 1926.

In Seattle, the African-American population increased from 400 in 1910 to 15,700 in 1950. For those who settled in Seattle, the promise of better jobs was tempered by the reality of institutionalized employment discrimination that relegated black workers to the lowest-paying jobs with little opportunity for advancement.

To illustrate, between 1910 and 1940, the number of Black men who worked as servants, janitors and waiters increased from just 45 percent to 52 percent, and the number of Black women who worked as domestic or personal servants stayed about the same, at about 83 percent.

And in housing, those who were just one generation removed from slavery experienced new types of controls over their lives. From the 1910s through the 1960s, in reaction to the Great Migration, restrictive racial covenants were established to bar nonwhite residents and sometimes Jews from living in many neighborhoods in Seattle, with housing deeds explicitly barring nonwhites from renting or buying property. These covenants, which still exist on many housing deeds today, effectively relegated Black residents to a small number of neighborhoods in Seattle — including the Central District.

Over time, Green and his five siblings established themselves in the Central District, having 23 children between them. Of the 11 homes the extended family ultimately owned in the general neighborhood, six homes were along a three-block stretch of 24th Avenue, several with adjoining yards. By the 1980s, there were 60 members of the Green family living in the family homes in the Central District. Family self-reliance, entrepreneurship and resourcefulness were paramount. Frank Green taught himself plumbing, electrical work and carpentry to maintain the houses himself, and passed on the knowledge to his children and grandchildren. Those children were encouraged to go into the construction trades, and an alternative family economy of learning trades and then hiring family members in those trades was born.

Wokoma, Green’s grandson, grew up in this milieu, surrounded by an extended, intergenerational family in a vibrant and walkable black community.

For Wokoma, the Central District was about more than housing and businesses — it was about home. “Black Seattle was very much a network of families. You knew them from their family name. There’s all these different ways you could be running into somebody on the street and you know there’s a half of degree of separation. …There’s a sense of home that extends out beyond the four walls of whatever your home address is. It extends out into the community.”

That belonging helped forge a sense of identity, freedom and the belief that hard work and commitment to community and family would pay off. “It was a place where you could be who you are with no complications, no caveats, as a Black person, as a Black human being,” he says. “You could express that in every way you were compelled to do that. Living in a Black community affords you the freeness to be your human self — unconditionally. We know what it means to have to censor your humanity as a means to survival.”

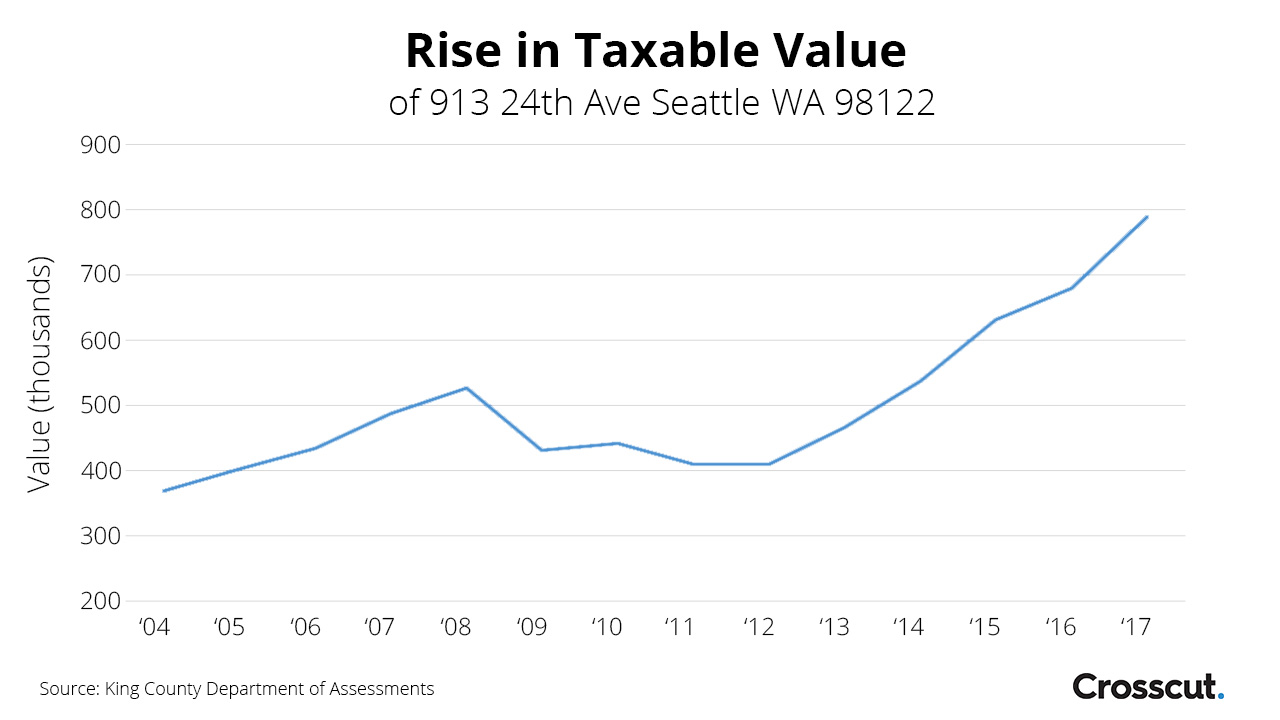

While Wokoma grew up in the heyday of the Central District, by the late ’80s, numerous strains began to tear the fabric of the Black community in general and the Green family in particular. Persistent wealth inequality coupled with economic redlining made loans for home improvements out of reach for Black homeowners. For members of the Green family, that meant that although they could do basic home maintenance, more expensive projects — like putting a new roof on a house — were out of reach. As a result, some homeowners sold. Wokoma explains, “My grandfather bought two houses for $7,000 and $10,000,” he says, but maintenance, especially as his grandfather became older, became more challenging and expensive. In this scenario, if someone offers you $150,000 to buy the house, “You may not want to sell your home or move out, but it may be the most pragmatic option you have. You replicate that across the entire community.”

The legacy of racial wealth inequality is a critical yet underestimated factor in gentrification and displacement. According to a report by the Institute of Policy Studies, a progressive think tank with a focus on economic and racial justice, between 1983 and 2013, in today’s dollars, Black median wealth (excluding durable goods) declined 75 percent from $6,800 to $1,700. At the same time, net worth for the median White family increased 14 percent from $102,200 to $116,800. Homeownership plays a big part in the wealth gap, with generations of White families able to inherit wealth through homes and home sales. Put another way, it would take 228 years for the average black family to reach the level of wealth a White family has today.

White flight from the nation’s inner cities to the suburbs in the ’40s and ’50s is well known, and Seattle was no different. But by the 1990s, White families in Seattle began returning to the city, once again interested in living in the urban core. In the Central District, this resulted in speculators targeting distressed houses that families were not able to maintain, and the homes of elderly people who needed the equity from their homes to stay afloat during retirement. As homes were renovated, White families moved to the Central District, raising property values and property taxes, and fueling displacement for families like the Greens. One by one, the Green properties left the family.

According to a 2017 story in The Seattle Times about the Central District, the homeownership rate among African-Americans in the city dropped by half between 2000 and 2013, with just one in five Black households owning its home. The number of Blacks in the Central District overall has plunged, now with just 20 percent of the neighborhood composed of African-Americans, down from 70 percent in the ’70s.

In 2005, in a desperate effort to save the first home Franklin Green bought in 1947, Wokoma and his wife purchased the duplex on 24th Avenue, although it was a stretch for them financially. Keeping up with maintenance on a nearly 90-year-old house was an overwhelming task. A leaking roof, old wiring and old plumbing all posed daunting financial challenges. At one point, they came close to losing the home to foreclosure. Now, Wokoma is maintaining the house himself and finally was able to put a new roof on it after 12 years. He continues to resist offers he gets in the mail at least once a month to purchase the house for as much as $1 million — sight unseen.

For Wokoma, saving the family home means more than saving a place to live. It means resisting the systemic inequality that is forcing Black families out of the Central District. “There were systems in place to make sure we lived in certain areas; once we lived in those areas, there were systems in place to make sure we had the least amount of economic opportunity possible: redlining, job discrimination, lack of small business loans. . .all these things are structural, and they all limit the amount of opportunity and resource that a community collectively has access to.”

Wokoma gets frustrated when hearing new White residents of the Central District minimize the challenges faced by Black families that try to keep their homes. “We have the same level of commitment and desire for what we want the pathway to be, but our ability is radically different.”

That radically different ability has meant that the majority of Wokoma’s family has left the Central District, following their neighbors and friends to scatter to all parts south — Tukwila, Renton, Kent, Skyway, Federal Way. Wokoma says he doesn’t even know where most of his cousins live anymore and has never been to their houses. The family connections that were fueled by proximity are gone. “I don’t know people who just didn’t want to live in the Central District anymore, they moved because they couldn’t afford the [cost of housing].”

There are some efforts underway by African-American community leaders and others to ensure a continued black presence in the Central District. One of these is through the Liberty Bank project, a partnership between Africatown, Black Community Impact Alliance, Centerstone and Capitol Hill Housing that will develop the former site of the Black-owned Liberty Bank into affordable housing and retail space for Black-owned businesses.

But Wokoma wonders if this effort is too late. “What are [returning Black residents] going to get when they get here? Are they going to be here and alienated by the community at large?”

Wokoma knows there is no way to turn back the clock on the change that has already displaced the African-American community in the Central District. But he would like to see the city take a hard look at the forces that laid the foundation for this change and for those who live here to ask themselves what kind of city they want Seattle to be in the future.

The ideal, he says, would be for people like him to be paid fairly for their jobs. “Or get a loan,” he continues, “so when I die, my kids could have [the house]; they could fix it up and maybe they can pass it on to their kids. I know that was my grandfather’s vision. He was not buying all these houses for himself. An honest conversation about the CD and all the things that facilitated the change in the CD provides an opportunity, collectively, as a society, as a city, as a county, as a state, as a nation, for us to reflect and potentially make better, more equitable choices in the future.”