The material is like a sturdy cotton sheet, the type they use in hospitals.

I’ve never handled one of these garments before, have never seen one, except in hundreds of images of the Ku Klux Klan.

My fingers feel the fabric, trace some of the seams. Someone made this. It’s not pulled from a bed, it’s been carefully crafted.

There’s a burst of color on the breast where one’s heart would be. A red badge, not unlike a Scout’s badge but bigger. It’s a red stitched circle with what looks like a white cross forming an “x.” In the middle is a square with a red drop that looks like half of the yin-yang symbol. Only it looks like a drop of blood.

There’s a belt and a cape.

And there’s the hood. The hood is stiff and flat with cardboard inside to keep its pointy shape. It’s topped with a blood-red tassel.

But the thing that gives me chills is the face of the hood with its eyeholes cut in oval shapes. Hoods are scary things, especially when they come with torches, carried by strangers. That was the point of this garment, to terrify. The eyeholes look worn from use, perhaps from sliding it on and off. The holes look as if they’ve been widened to fit a particular man’s eyes. A Klansman’s got to see, especially at night.

The Klan hood seems less generic as I look it over. Someone wore this. Not a faceless person, but someone’s father, uncle, grandfather. It’s not a costume, but a weapon. Someone hung it in a closet in Astoria, Oregon, probably in the 1920s and left it for their descendants to find along with the old dark suits. White like a skeleton.

How many Astoria residents have found KKK robes in a family closet or attic trunk is unknown, but fortunately at least four people have anonymously donated these old Klan robes and hoods to the Clatsop County Historical Society’s Heritage Museum. (The museum has more Klan relics too: a ceremonial sword, belts, patches, a felt pennant — as if the KKK were a sports team.) I say “fortunately” because this is Northwest history that is easily lost, forgotten, and buried. It’s important that this history, hateful as it is, be saved so people can look at it, feel it—not only in their hands, but in their hearts. To me, the horror of the Klan became touchable, less abstract.

Photographer Matt McKnight and I came to Astoria largely because of the reason such things have wound up in the local museum: Back in the early 1920s, as the KKK bloomed nationwide, Oregon was one of the top two states in membership, with Indiana. With an estimated 35,000 members at one point, Oregon was the center of the Klan in the West.

Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River was second only to Portland in being the state’s biggest Klan center. In the 1920s, Astoria’s population was peaking at around 14,000 — with at least 1,000 KKK members and thousands more who sympathized with the Protestant, native-born, white supremacist agenda. The Klan had power to dominate elections in the city and helped influence government across the state of Oregon, and to a lesser extent in Washington.

The Pacific Northwest has all sorts of shameful but important history around the Klan, anti-Semitism and bigotry directed at Blacks, Asians, Native Americans and Catholics. Over the past few years, I’ve written about Seattle’s racist mayor of the Civil War era, the Seattle-based pro-Hitler presidential campaign of the leader of the 1930s Silver Shirts, and racial exclusions and expulsions of people of color throughout the region’s history.

So, the strength of the KKK in Astoria caught my eyes and seemed like an intriguing case of a community succumbing, for a time, to its worst fears and prejudices.

We came to find out why its history had gone awry. And we wondered: What do you do when you have artifacts like these? And what might they tell us about the Northwest today?

To the first question, why was the Ku Klux Klan such a big deal in Astoria? It was a boomtown with the demand for Northwest products — timber, canned salmon, ships — growing after World War I. It was a rough and tumble city with a longstanding vice district — called Swilltown — to feed those workingmen’s appetites for gambling, sex and booze.

It was full of immigrants — most from Nordic countries, especially Finland, whose residents — in one of the stranger twists of racist thinking — were sometimes regarded as non-White. History Professor David Horowitz of Portland State University has studied the Klan in Oregon. “Astoria may have been a magnet because it was a port and potentially a place of entry for illegal booze, merchant seamen, Chinese immigrants, and the various vice trades associated with that status,” he tells me. It “also had a large population of Finns, known for their political radicalism after the Bolshevik Revolution.” In the years following World War I, anti-communism became strong in America.

So too had a trend toward uber-nationalism, a sense of worry that America was become “mongrelized” and subverted by foreign influences. It’s easy to forget that Oregon had racial exclusion laws — yes, laws excluding Blacks and mixed-race people altogether — dating back to the mid-19th century. Oregon banned Blacks in its state constitution, a provision still there until 1926. These laws discouraged racial minorities from living within the state’s borders. So, the Black population was small and limited mostly to Portland; there were a few Jews and some Japanese farmers.

In the early 1920s, the KKK took off and extended throughout the North, Midwest and the West Coast — not so much as nightriders terrorizing Blacks but as a middle-class movement that was white supremacist as well as virulently anti-Catholic. Oregon’s population was White, Protestant, and native born, which met the KKK’s male membership requirements. Linda Gordon, a New York University professor and Bancroft Prize-winning author, has written a new book, “The Second Coming of the KKK,” that focuses on the Klan’s 1920s revival. She writes, “The combination of economic and cultural factors and a rich vein of possible recruits contributed to the Klan’s high-velocity Oregon success.”

The Klan sought to eliminate the “anti-democratic,” foreign influence of the Pope and his followers. Its members distrusted immigrants. They wanted Prohibition enforced. They feared change and urbanization. For many, the KKK became their vehicle for “reform” and restoring traditional American values — for making America great again.

Oregon’s Klan began to grow in 1921, but the following year was a watershed one. The Klan pushed a statewide initiative in 1922 to ban all private schools, especially Catholic schools. The vision was that Oregonian’s children should all go to public schools and be thoroughly Americanized with the same curriculum emphasizing god and country. Though a similar Klan initiative in Washington would later flop badly with voters, the Oregon initiative passed, only to be eventually overturned in court. Klan-backed candidates won the Oregon governorship and many legislative seats, virtually controlling the state’s Legislature.

The Klan tide swept Astoria. The KKK had installed their choice for Clatsop County sheriff that year. They also used threats and intimidation to run Catholics out of positions on the school board and as the head of the Chamber of Commerce.

Their campaign for control culminated with the November election. The banner headline in the Morning Astorian on Nov. 8 read, “Ku Klux Klan Ticket Sweeps City.” The KKK took the mayor’s office and all the city commission seats. The Klan became City Hall.

The Clatsop museum has physical examples of the tactics used to gain influence. One is an anonymous “special delivery” threat from an Astorian to a man with an Irish Catholic sounding name, Tom McKay. “Your case is not forgotten,” the note reads. “The right opportunity will come. [Signed] K.K.K. 876.” Accompanying the note was a clipping about a series of brutal floggings doled out by the Klan in Tulsa. Clearly, McKay was being threatened with the same treatment. Oregon had its own history along that line: When it banned all Blacks, those who exercised their constitutional and human rights by remaining were threatened with public whippings.

Some of the community pushed back. The crackdown on saloons proved hard to enforce no matter who was sheriff. Some clergy protested, but most sided with the Klan and many non-members said they agreed with Klan values, if not tactics. One Klan stratagem the clergy may have liked: KKK members in full regalia had ceremoniously entered local churches during services and donated money with a flourish.

Journalists stood up against the Klan. The KKK — on the letterhead of the “Imperial Palace” of the national headquarters in Atlanta — demanded the removal of the editor of Astoria’s Evening Budget newspaper, M.R. Chessman, who editorialized against them. In lieu of that, the Klan offered to buy the paper outright. Chessman stayed and the Budget rejected the offer.

The KKK had their own PR machine. Astoria became the headquarters for the Klan’s Western newspaper, The Western American, edited by Lem A. Dever, a former journalist who, among other things, once worked for the Seattle Chamber of Commerce. He helped spread their virulent message far and wide.

The fever that saw the Klan’s torches shine bright in the early 1920s broke later that decade. The Klan organization fractured into camps, and loyalists like Lem Dever split with the organization over corrupt practices, internal infighting and political power struggles. People grew tired of the KKK’s intimidation tactics and occasional vigilante behavior. By the early 1930s the Great Depression came and Prohibition was overturned.

As the KKK diminished in strength, white robes ended up in closets.

Fast forward to the late 1990s when the Clatsop Museum’s curator at the time, Mark Tolonen, mounted a museum exhibit on Astoria immigration (Tolonen himself is from an old Astoria family with Finnish heritage). Astoria was a town of immigrants, and for a time, anti-immigration activists. The exhibit included some of the Klan artifacts, among them a white robe.

Stories appeared in regional newspapers from Portland to Seattle about whether or not exhibiting such artifacts was appropriate. Some thought they glorified the Klan. Others objected to raking up a shameful past. Some contended it wasn’t a significant enough matter to warrant attention — the KKK was, supposedly, a mere blip in the history of the Northwest coast’s oldest Euro-American settlement, better forgotten.

And people have forgotten, or don’t want to talk about it. I asked one multi-generational Astorian about the KKK and he pantomimed a 10-foot pole and held me at bay with it.

Klan robes and hoods can absolutely make people very uncomfortable. The Washington State History Museum displayed a blue Klan robe as part of a Civil War exhibit a few years ago — I wrote a column about uneasily trying to explain it to my then 9-year-old African American granddaughter. When I told her what the Klan was about, she dismissed them as the Klu Klux clowns. Still, my grandkids need to know our real past, and how it informs the present. Museums can show us how we got the way we are, warts and all.

The Oregon Historical Society collection includes KKK robes, hoods and other artifacts from Oregon’s Klan era gathered from around the state. Some Klan artifacts were included in an exhibit curated by Oregon Black Pioneers in 2013. Context is important. Neither generated any memorable impact for their respective museums, according to current curators. Interestingly, even though there was a significant KKK presence in Seattle, the Museum of History and Industry has no Klan robes in its collection. Which means there are likely some unopened closets around Seattle with cotton skeletons in them.

Mark Tolonen is now curator with the Benton County Historical Society and Museum in Philomath, Oregon. “The white robes and hoods in that exhibition about immigration create a very powerful spectacle,” he says now about that earlier Astoria exhibit. Looking back he says the larger message about immigration being part of the community’s history “is easily lost when powerful artifacts” like the robes and hoods are displayed.

Liisa Penner is the Clatsop museum’s archivist. A Klan sword and pennant are on exhibit, but the hoods and robes are in storage. When Matt and I visited, they were brought out for us to look at and photograph. Penner has files and boxes of correspondence, clippings and other documents related to the 1920s Klan in Astoria. If the community is uncomfortable with this history, the museum is certainly not averse to making its files and collection available to researchers and keeping some reminders on display. Donors of KKK items often deny knowing that their family members were Klan members and they all have insisted that their family names not be connected with the robes. Still, the fact that they have been donated to the museum suggests an understanding of their historic value — and maybe a desire to get them out of the house. The Klan itself was secretive about members, but also very public. Its members wore hoods and conducted secret ceremonies. Some saw it as just another fraternal organization, like the Odd Fellows. Many were uncomfortable with its tactics and pageantry, but not its messages of racism, nativism, anti-Semitism and “Americanism,” just as many people who would never wear Klan robes today find themselves in sympathy with the ideas of the nationalism and what some call the “alt” right.

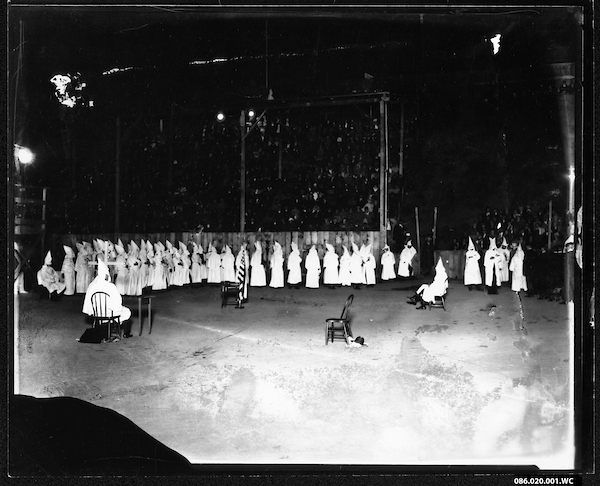

After looking through materials and photographing the Klan garb at the museum, Matt and I left. But we had a copy of a photograph from the museum’s collection. It was taken at an Astoria Klan rally in 1924. That year, the town hosted a Klan convention and more than 10,000 Klansmen and their supporters came to town.

The photograph shows what appears to be a ceremony inducting new members into the Klan. They are wearing their white hoods and robes and appear to be in a field. A grandstand filled with spectators is in the background.

A newspaper account from the Astoria Budget fills in the background of the photo: A KKK parade led by five Klansmen on horseback marched through town to Astoria’s Columbia Club Park where more than a score of candidates were inducted into the Klan in front of a large crowd while “a great fiery cross blazed in the background.” They were welcomed by the mayor, O.B. Setters, and the Oregon KKK’s grand dragon, Fred Gifford, who “spoke eloquently upon ‘100 percent Americanism.’ ” The paper described the scene as “an unusual and interesting one.”

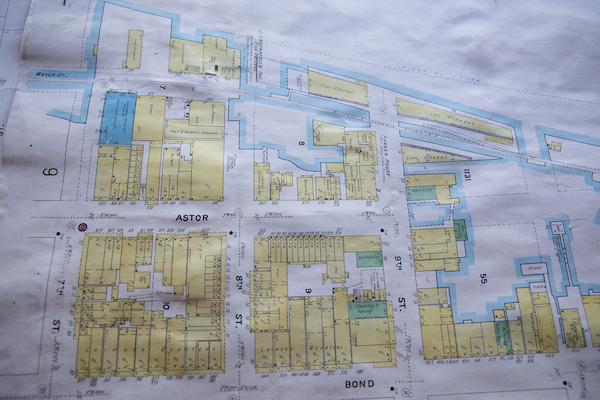

While I was going through my KKK notes at our hotel on Astoria’s riverside, Matt called me and said he’d learned that the park in the photo still existed and in fact was very close to the hotel. We’d driven by it a number of times. We went over and looked. It’s a baseball field — as it was in the ’20s — currently “Home of Astoria’s Youth Baseball.” As in 1924, John Jacob Astor elementary school sits above the park — we could see and hear the children playing on the playground likely near where that fiery cross once burned near the banks of the Columbia River and perhaps cast its reflection.

The scene today is so normal: a school, a ballfield right on the main road into town. Seeing the Klan ceremony photo from 1924 and looking at the park now, Hannah Arendt’s phrase about “the banality of evil” in reference to the Nazis came to mind. Rather than being extraordinary, evil is often ordinary, woven into the fabric of our history and everyday life, hanging in our closets, lingering as bad ideas. Our discomfort with the history is evidence that the resonance in the present is real.

That realization was as disturbing as handling those white robes of common cloth.