My first record purchase in the fall of 1979 was the 12-inch single “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugarhill Gang. I knew nothing about this song except that the Sugarhill logo on the record jacket reminded me of candy (I was nine-years-old at the time). And, the person at the counter seemed to approve of my choice. Although the bassline sounded familiar, when the vocals began I was thoroughly confused. Why were these people not singing? Who makes a record and just talks over the beat? But then I heard: “I got a color TV/so I can see/the Knicks play basketball.” This music immediately spoke to me.

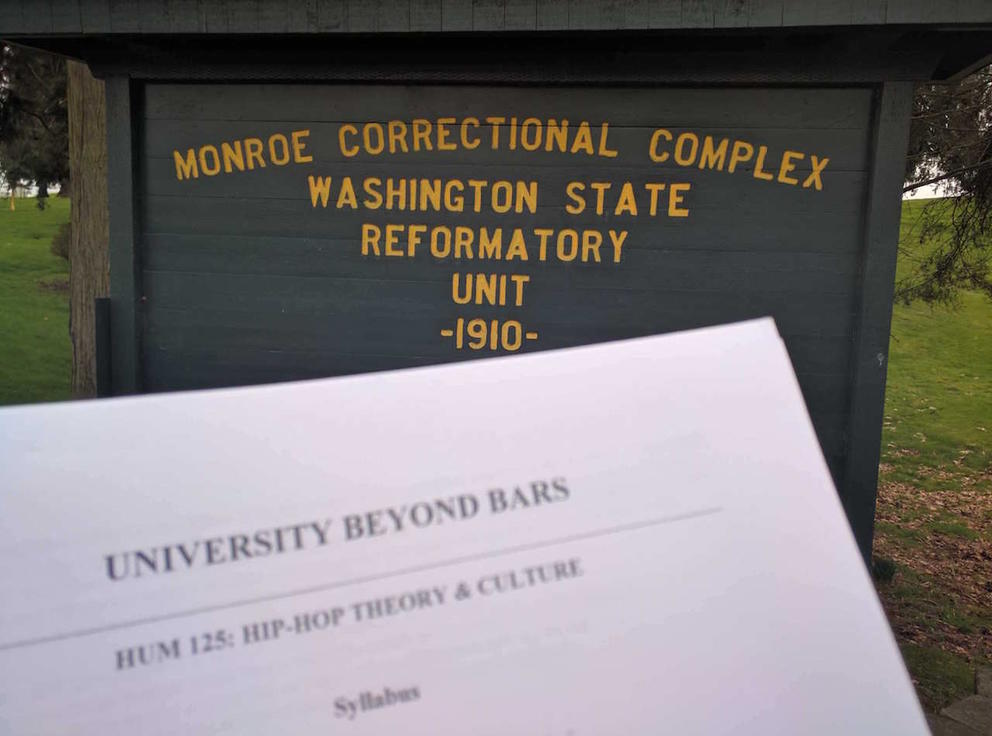

Fast forward some two decades: I begin teaching at Seattle Central College. My Humanities 125: Hip-Hop Theory & Culture class debuts in 2003 with 30 students on the wait list. Since then, I have taught versions of this class not only to college students, but to high school and middle school students as well.

This past winter quarter, the class led me to the most unique professional situation I’ve experienced during 25 years in the field: teaching the hip-hop course to students at the Monroe Correctional Complex on Wednesday evenings followed by Thursday afternoons leading an elective class called Comprehending Hip-Hop for high schoolers at The Bush School in Seattle. I was immediately struck by the range of life experiences between both student groups.

At Monroe, University Beyond Bars offers an opportunity for male inmates to earn college credits and degrees, regardless of prison sentence — and there were several lifers enrolled in this class. Founded in 1924, Bush is a small, private, non-denominational K-12 school in Seattle’s Madison Valley that costs nearly $35,000 a year for grades 9-12. Although it is an overwhelmingly White school, there was good racial, gender and grade-level diversity among the students in the hip-hop elective. The same was true for the class at Monroe, except for the gender part; the students ranged in age from mid-20s to mid-60s.

From the start, the approach of this class has simply been to use hip-hop as a lens for students to critically analyze and discuss larger issues such as race, class, gender and social justice. There was considerable overlap in course materials, and as a teaching geek, I was super interested in the similarities and differences between how these two groups of students would process and reflect on the curriculum.

At Monroe, there were nearly 30 students registered. I am fairly anal about being organized and having every class session planned before the quarter begins. But I quickly learned that in a prison situation the schedule is at the mercy of prison situations. Our first meeting, which was supposed to be 2 hours and 40 minutes, began almost an hour late because of an altercation that locked the entire facility down for a time and landed one student in the IMU (Intensive Management Unit) for two weeks. In addition, a number of students had to regularly leave 45 minutes early in order to take a shower and eat dinner before lights out. By the time the end of the quarter neared, I was moving pieces of the course curriculum around like I was playing Tetris.

As in every class, at Monroe there was pain, there was joy and there was reality. The pain: part of the curriculum covered the crack epidemic of the 1980s and hip-hop’s response to it (Public Enemy’s “Night of the Living Baseheads,” for example). The reflection paper on this topic drew numerous personal stories of students’ experiences with the drug; several stories were also stark reminders that some of these guys had done really terrible things. The depth of regret, anger, sadness and hope in their writing was unlike anything I’d read in the history of this assignment.

My teacher’s assistant Chris, who grew up on the Hilltop in Tacoma, wrote, “It was as if my neighborhood was part of a movie, life was that crazy. People that did not grow up in the thick of this epidemic could never understand the damage that was caused by it. I have witnessed the worst of what this drug can do to the people that are in its path. I am sitting in prison with a 45-year sentence because of my actions and the path I chose from what this and other drugs have to offer.”

The joy: something that made me smile was the midterm exam. Questions ranged from identifying the signs of neighborhood social disorganization to an essay requiring the creation of an original graffiti piece with a detailed explanation of its stylistic elements. The review session and test were the same as they had been for my Seattle Central students at the college, but the Monroe class average of 95% was the highest of any class I have ever taught.

The reality: although the classroom we used felt like any other once class began, the heavy-ass steel doors closing behind you, the airport-like security procedures required for entry, the bars, the tall fences with razor-laced barb wire and the khaki prison uniforms of the students were all reminders that overall, the Monroe Correctional Complex is a grim place.

The group at Bush was about half the size of the Monroe class and our meeting room, which had a fireplace with a large oil painting of school founder Helen Bush over it, was in a majestic, college-looking brick building. I taught the class with local hip-hop veteran Spyridon “Spin” Nicon. Perhaps the highlight for the Bush students was a live DJ demo/lecture by DJ Topspin, aka Blendiana Jones. (Any thoughts of doing something similar at Monroe were squashed upon learning that equipment like two turntables and a mixer would take 2 to 3 months to be cleared for prison entry). But for all the differences between both groups of students, there were similarities. Students in both groups arrived late and left early, got distracted, doodled, cracked jokes and occasionally had small conversations on the side while I was lecturing.

Early on, I could not help but tell the two classes about each other, and immediately there was mutual fascination. The students at Bush were interested in the life paths that led their counterparts to prison. The students at Monroe wanted the Bush students to maximize their privilege. When I asked each group for a quick message to deliver to the other, Monroe overwhelmingly said, “Take advantage of your opportunities,” while Bush answered, “Don’t give up hope.”

Building on this, an exercise that drew great enthusiasm from numerous students at both sites was the chance to write anonymous “To Hip-Hop It May Concern” messages to the other group — the idea being to think about the class topics that most resonated. What life lessons can be learned and how would you express that to your student counterparts? It was apparent how much some of the Monroe students valued this simple exercise: “I feel blessed to be sharing this hip-hop experience with you. I have been incarcerated for 10 years and I am only 28. To be connected to the outside world is something that all of us deeply desire,” one student wrote.

Others at Monroe used hip-hop’s incredible and unlikely rise from simple beginnings to deliver hope signals:

- “Although your social situation is different from the kids who created hip-hop, express yourselves the way you want to. At some point we all feel unheard, misunderstood or unappreciated.”

- “Those kids from the South Bronx didn’t think they’d affect the world; however, hip-hop has done just that. You all possess the ability to create something monumental.”

- “This class, focusing on the sociology and history of hip-hop, has revealed a striking and poignant message: make yourself be heard.”

- “My advice to you is to be always open-minded about someone else’s beliefs, culture, and interests. So embrace one another so that we can all learn from each other.”

The Bush students responded in-kind.

- “It’s hard to know what to say, we both have such different lives and especially having learned much about the failures of the American justice system, it’s even more difficult to know what to say given a lack of justice you may or may not have.”

- “We loved reading your letters and found your messages inspiring and your stories thought-provoking.”

- “My hope is for all of you that you are able, if you have not already, find what makes you happy.”

I kept wondering about how interesting small group discussions might have been between the two classes. I learned my students at both places had similar thoughts.

“We wish we could’ve taken this class alongside y’all, but we are very stoked to have gotten to communicate in some way.”

“It would have been great for our classes to take it together.”

As the Bush class ended, we shared a line from a Monroe student named Elijah. Speaking for the male inmates who are largely forgotten, he reminded the Bush teens of something universal that can apply to whomever, doing whatever, wherever:

“Make education your hip-hop. Listen to its beat, rhythm and style because it is your turn to rock the mic.”

That moment reminded me of what it means to be a teacher cultivating positive interactions with their students. We must all aspire to be educators who lift up aspiring mic rockers regardless of their environment.