These days, Malm is spending more and more of her time assisting residents in their 60s, 70s, 80s and even in their 90s from becoming homeless for the first time in their lives. The 54-year-old Malm is not all that different from her clients. She is single. She lives paycheck to paycheck, hoping to God she doesn’t become sick. She understands the fear and angst of her elderly clients.

“Most of their funds are going toward housing, leaving little for food or medical help,” including doctor visits and prescriptions, Malm said from her small office located on the ground floor of the Good Shepherd Center in Wallingford..

In December, The Seattle Times reported that Seattle is one of the five most expensive big cities in the nation for renters. It also has the fastest-rising home prices in the country, and an aging population. According to 2010 census data, 10.8 percent of Seattle residents were 65 and older. Looking at King County as a whole, it’s expected that by 2040, 25 percent of residents will be 60 and older — up from 18 percent today.

Older adults living on fixed incomes are finding it increasingly difficult to remain in the neighborhoods where they have lived for decades, Malm says. Although rent hikes threaten the majority of her clients, reverse mortgage problems and an inability to pay for maintenance and upkeep for the few who own homes are also at play. Oftentimes, her clients have waited as long as they can before contacting her. By then, they’re in crisis mode and in need of immediate housing.

It wasn't until later in life that Malm decided to become a social worker, attracted to the career because “she was drawn to being with people who our society doesn’t view as important.” Once her two children had grown, she pursued undergraduate and then graduate work at the University of Washington. She was one of the oldest students in her program.

As a middle-aged woman, she felt as if she didn’t always belong. But with the constant encouragement of close friends, she created a team for herself, a constant cohort to help her get through the program.

This is the same approach she uses today with her clients at the Wallingford center. She asks: “Who’s going to be on your team?” to help them get through hard times.

Four years ago, when she was an intern, Malm says her work “felt easy and short-term.” She’d meet with clients a couple of times. “It wasn’t this ongoing need for help and support.” Clients, she recalls, needed help with finances, navigating housing inspections or Medicaid. She dealt with everything from suicide prevention to giving dating advice to a 95-year-old man. But she only remembers helping two people over the course of that time with a housing crisis.

“Now, on average, I receive housing assistance calls weekly,” Malm says.

Her days are never the same. She has seen up to five people a day (Appointments are free for up to four sessions; after that clients are charged on a sliding scale). Some are previously scheduled appointments, some are walk-ins. For those with urgent issues, 60-minute sessions will turn into 90-minute ones if she can make it work.

Most of her housing clients are women in their 60s and 70s who are most often single and who haven’t had working careers. Many were once married, but spouses have passed away or they’re gone due to divorce. Some clients don’t have children, and their friends have either moved away or died. They lack a support group and now find themselves without Social Security benefits or a retirement plan — things that men often have and can fall back on.

Clients vary, says Malm. There is the 65-year-old woman who, after taking care of her children as a stay-at-home mother, turned her attention to her elderly father. A widow, she came to the harsh realization after her father’s death that after years of taking care of everyone else, she lacked the financial resources to take care of herself.

Or, the 82-year-old woman who called Malm in a panic because she could no longer afford to live in her apartment after her new property owners raised the rent. Living off of her monthly Social Security check, she had little choice but to move. Living in a state of nonacceptance, the woman waited until she had one month left on her current lease before seeking Malm’s help to find housing.

Malm explained it is not unusual for fear and denial to take hold in crisis situations, preventing her clients from being more proactive. It’s stressful for them; they can’t afford a mental health counselor so they seek out Malm, who listens.

“Where can people who don’t have much money get that?” she asks.

Working as a senior center social worker in Seattle can be very isolating. Malm discovered early on that there was no pre-existing system of communication in place among social workers; she was working in a silo. Sound Generations, which operates seven senior centers throughout the region, organizes quarterly meetings for social workers. But four times a year is not enough time, especially given that social workers are usually the only ones of their kind at senior centers, Malm says.

“It’s emotionally exhausting to sit with someone and try to figure out their problem,” Malm describes. “This person is right in front of you asking for help. It’s like they’re drowning and you’re swimming out to get them and you’re barely treading water. And you have to get back to shore and breathe before the next person comes.”

Last January, Pike Market Senior Center (PMSC), with a grant from United Way of King County, partnered with the Wallingford center in developing Project SHARE (Senior Homelessness Action, Resources, and Education). The project created opportunities for social workers to meet on a regular basis with staff from PMSC and the Wallingford center.

At those meetings, participants kept hearing about how often social workers encounter elderly residents who were forced out of their homes due to the rising cost of living.

“Our concern is that this is an invisible epidemic,” said Mason Lowe, PMSC’s grant writer and bookkeeper.

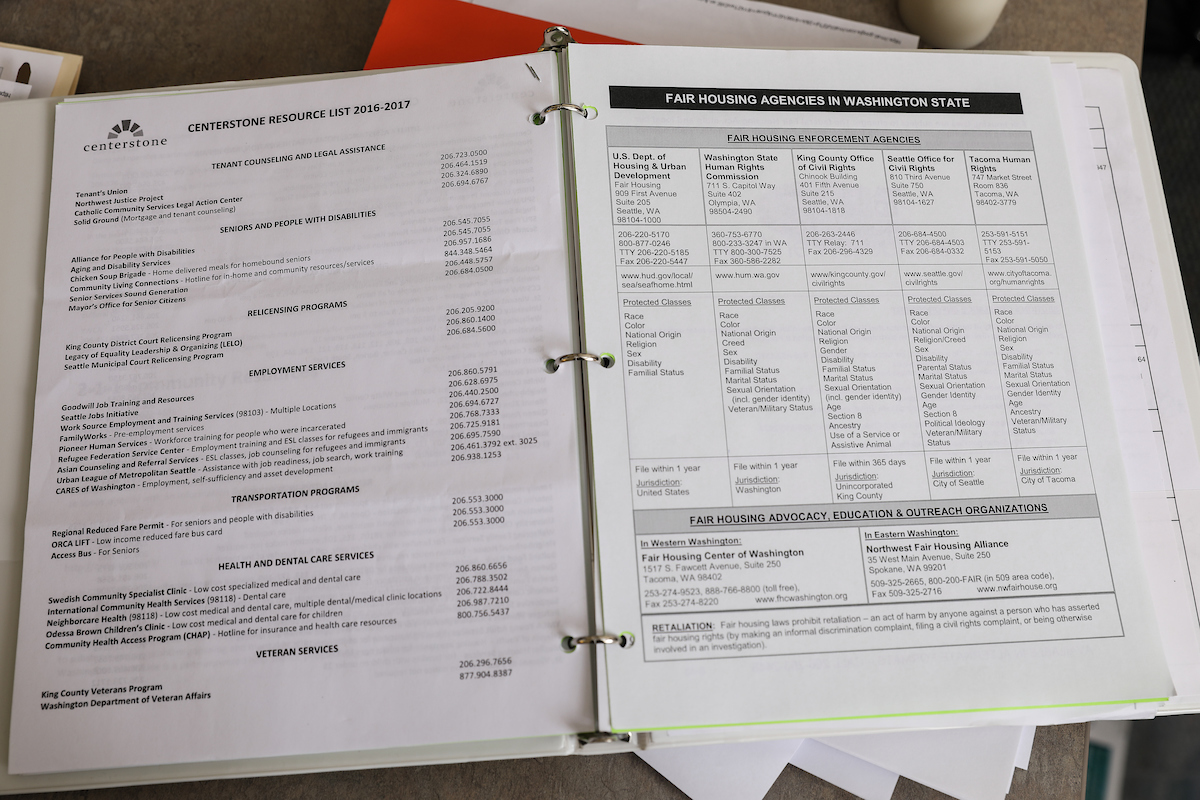

The year-long Project SHARE collaboration culminated in the creation of a resource book and an accompanying FAQ pamphlet for social workers who help elderly clients with immediate housing needs. The book offers information on affordable housing terminology (the difference between Section 8 housing versus transitional housing, for example); area shelters; rental assistance and eviction prevention.

PMSC has distributed the 9-page FAQ and resource book free of charge to all 36 senior centers in King County. The resource book was distributed to the six participating senior centers in Project SHARE and a downloadable version will be made available to all other King County senior centers.

Wei Wei Zhang, a social worker at Seattle’s Central Area Senior Center, is already using the resource book. She says it is very clearly categorized so it’s easy for her to find the information she’s seeking. “When I go online, I never know what to look for,” she said.

Malm says her involvement with Project SHARE has made her realize just how great the need is for housing assistance — and the need for more available resources to help clients navigate the bureaucracy.

Online assessment forms are one example. What if a client doesn’t have access to a computer? Or isn’t tech-literate? A paper form can be mailed in but those take longer to process, which means benefits could be delayed. A client could visit a Department of Social and Health Services site to do the paperwork but that raises possible transportation issues, which can be another barrier for older adults, Malm says.

Malm has come to realize what it means to be able to walk someone through the process — or how to cushion the blow if help isn’t immediately available.

“What do you tell an 82-year-old woman who has never been homeless before, that there is nothing in this area for you?” Malm asks.

Her answer: “We brainstorm temporary housing such as couch surfing with a friend or relative. I will also give them a list of different low-income housing buildings to call or visit directly. We also have hard conversations about moving out of their community and searching for options in other counties.”

All too aware of how a “silver tsunami” — increasing numbers of elderly Seattle residents — is approaching, Malm is hopeful. It's the first year King County’s Veterans, Seniors and Human Services Levy will provide funding for vulnerable seniors, and the levy could generate more than $25 million.

She wonders if competition for new county funding will intensify among social service providers who have weathered years of budget constraints. And she considers what senior centers like hers could do if awarded funding: They'd do more outreach so social workers could have an even bigger impact on clients. But for now, Malm will continue to tread water, despite the "tsunami" that doesn't look to be letting up.