Could Washington trigger a Trump administration lawsuit against the state over net neutrality?

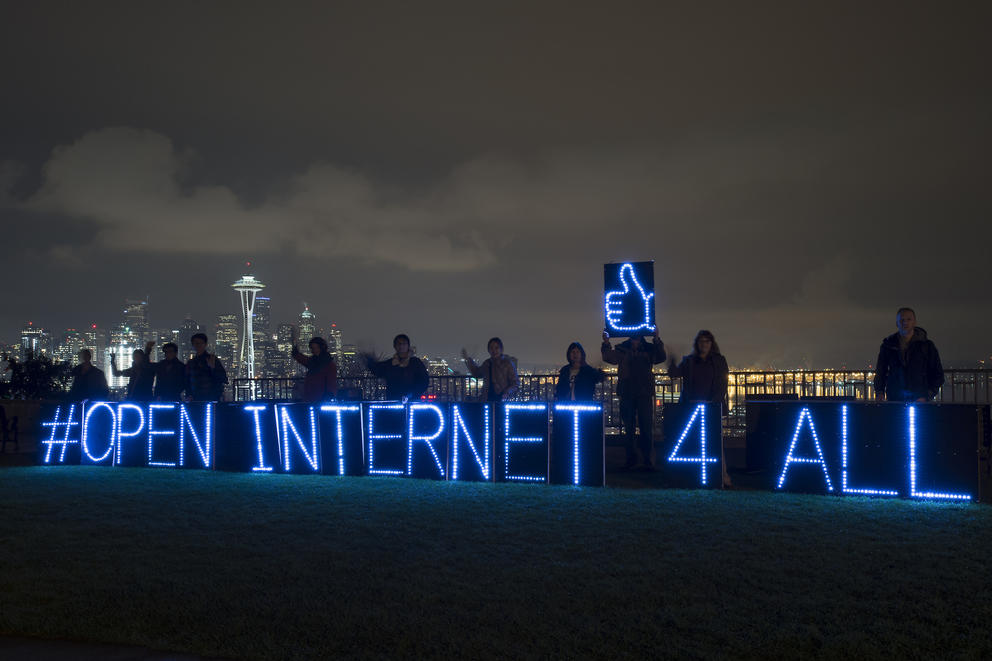

Washington’s Legislature, which is delving into internet issues this year, appears likely to pass a state law requiring net neutrality here in defiance of the Federal Communications Commission. With a chair appointed by Trump giving Republicans a majority on the commission, the FCC voted in December to dismantle rules that forbade broadband providers from slowing down some sites or giving special treatment to websites that pay extra — a move long sought by major telecom companies.

Washington is exploring a law to continue the old rules, but broadband groups recently warned lawmakers that a statewide net neutrality law might spark legal action by the feds. They suggested the state's move could violate federal interstate commerce laws.

“The likelihood of a lawsuit is great,” Gerald Keegan of the CTIA, a wireless business association, told the House Technology & Economic Development Committee.

However, Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee’s staff has studied what might happen if the feds challenge Washington for going solo on net neutrality. “We are on firm ground,” Inslee said last week. “We have analyzed our legal standing.” A number of states, including Washington, have already announced their intent to sue over the FCC's action; state Attorney General Bob Ferguson says the repeal failed to follow federal law on administrative procedures.

In what appears to be a bipartisan groundswell in favor of securing consumer access, the Legislature wants not just to hang onto net neutrality but also to keep internet service providers from selling personal data to other businesses — measures opposed by big broadband companies. Republicans and Democrats also want bigger and faster internet capabilities in both urban and rural Washington, but those measures actually enjoy support from big broadband.

The Legislature is venturing into uncharted territory, trying to regulate an industry that is quickly evolving with the feds lagging behind. “We need multiple states to take action because nothing is happening at the federal level,” said Sen. Kevin Ranker, D-Orcas Island. During a Senate hearing on one internet bill, Sen. Doug Ericksen, R-Ferndale, asked: “How do you regulate things fast enough as they are moving? . . . How does the state regulate what you’re going to do tomorrow?”

Lawmakers in other states — including Oregon and Idaho — are also talking about protecting net neutrality on a statewide basis, and the California state Senate last week passed a neutrality proposal. On Monday, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, a Democrat, became at least the third governor to sign an executive order requiring adherence to net neutrality rules by any internet service providers doing business with the state.

Net neutrality is the concept that broadband providers legally cannot stop or slow down internet service for some users and not others. The Obama administration’s Democratic-controlled FCC installed nationwide net neutrality with a 3-2 party-line vote in 2015. Similarly, the Trump administration’s GOP-tilted FCC revoked net neutrality nationwide last year by a 3-2 party-line vote.

Two House bills by Reps. Drew Hansen, D-Bainbridge Island, and Norma Smith, R-Clinton, would forbid internet providers from blocking content, degrading or slowing (called “throttling”) traffic on the basis of content, or to favor some traffic over others. Also, internet providers in Washington would be required to disclose information about network management practices, performance and commercial terms. Washington’s Attorney General’s Office would enforce the law under the state Consumer Protection Act. Ranker has a similar bill in the Senate. All the bills have strong bipartisan support.

In testimony before House Technology & Economic Development Committee, Hansen and a longtime tech employee, Logan Bowers, argued that the bills would keep broadband providers from showing favoritism in providing services and would help new businesses stay competitive with bigger, more powerful corporations. “There are plenty of examples in the last 20 years of ISPs manipulating the internet to their advantage,” Bowers argued.

Meanwhile, Keegan of the CTIA and Ron Main of the Broadband Communications Association of Washington countered if Washington establishes its own bastion of net neutrality, it could be the start of a patchwork of different internet laws that vary from state to state. Telecom officials have said such a system would constrain internet service, while also breaking federal interstate commerce laws. Keegan and Main also said that broadband providers don’t have discriminatory practices favoring some providers or content and have pledged not to do so in the future.

“I don’t see why you oppose a bill that prohibits you from doing something you don’t do,” said Rep. Richard DeBolt, R-Chehalis, a member of the committee.

Lawmakers are also looking at whether to require strong consumer privacy protections by internet service providers. Last spring, President Donald Trump signed a law that allows internet providers to sell personal information without consumer permission. A significant and largely hidden world exists of data brokers who buy and sell such digital information, according to a 2013 congressional report.

Washington lawmakers from both parties fired back quickly after Trump's action, introducing bills in the Senate and House to reinstate those protections in this state. Three-quarters of the Legislature supported the bills. The House overwhelmingly passed its version. But the Senate’s then-GOP leadership would not let its version go to a floor vote.

This year, Hansen introduced a tweaked version of the same bill, and it appears to be smoothly sailing through, with 75 out of 98 House members already signed on to it. The bill requires internet providers to obtain consent from users for accessing, using and disclosing certain customer information. The bill also requires the ISPs to provide notices of privacy policies and take reasonable security measures. Hansen and Alex Alben, head of Washington’s Office of Privacy and Data Protection, argued that internet providers should not profit from using customers' information. They believe some ISPs intend to use that personal data.

Representatives from the CTIA, the Association of Washington Business, TechNet and the Broadband Communications Association of Washington opposed the bill. They argued that the Federal Trade Commission can already enforce privacy rules. They contended that ISPs don’t abuse their access to personal data and already don’t share that information without the customers’ consent.

Michael Schutzler of the Washington Technology Industry Association testified that Congress is the best body to tackle this issue. He also suggested a Washington-only ISP-privacy law could spark litigation.

There’s much more unanimity on assuring expanded access to high-speed internet service. Washington state, like the country as a whole, is getting set to tackle the next generation of wireless technology — dubbed “5G” for fifth generation.

National 5G capabilities are expected to materialize between 2018 and 2020, depending on who is doing the predicting. The Trump administration briefly flirted with the idea of creating a national 5G network, but that trial balloon quickly died.

A bill by Sen. Tim Sheldon, a Potlatch Democrat who caucuses with Republicans, and Sen. Reuven Carlyle, D-Seattle, seeks to ensure that cities of 5,000 people have a permitting process for siting small cell facilities when a service provider wants to install a small-cell transmitter. Existing city laws on this subject would remain intact. The bill would also create a state Office on Broadband Access to help cities work on their permitting processes and to find grant money to help install 5G networks.

Representatives from several cities and broadband organizations testified in favor of the bill.

DeBolt, the Chehalis Republican, has introduced a bill to help rural areas address the so-called last-mile problem — homes, businesses and occasionally schools that are too far from WiFi or cables to have broadband access. DeBolt’s measure would fund $300 million to help rural areas upgrade their broadband services so computers in the remote areas can keep up with their big city counterparts. “We have areas that don’t have access to broadband,” DeBolt said.

Carolyn Logue, lobbyist for the Washington Library Association, said rural libraries are often the center where kids from homes with little or no internet access can do research. Many of these libraries have substandard broadband. She also added that seven of Washington’s 295 school districts have no broadband access.

“These kids can’t do their homework. They can’t get that ‘last mile’ to their homes,” said Wes McCart, a commissioner for Stevens County northwest of Spokane.

Correction: This article has been updated to correct the misspelling of Carolyn Logue's name.