Many folks are familiar with “Washington Crossing the Delaware," Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s classic 1851 painting of a pivotal episode in the American Revolutionary War.

But how many of us know Robert Colescott’s prickly parody of it, “George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Pages from an American History Textbook,” which burlesques a whole history of racial stereotypes?

In his 1975 painting, Colescott (1925-2009) takes an iconic American art history moment and turns it on its head, replacing Revolutionary soldiers with a boatload of surprisingly jolly African-American men fishing, strumming a banjo, swigging whiskey. The late African-American artist both mocks an old Western art genre — history painting, which usually took the form of epic-scale oils depicting everything from classical/biblical mythology to battlefield victories and government pageantry — and makes his own uses of it.

That’s a central theme of “Figuring History: Robert Colescott, Kerry James Marshall, Mickalene Thomas," now up at Seattle Art Museum. The show reveals how three artists of color have repurposed pivotal Western artworks and retroactively written themselves into a narrative that has historically shut out anyone who wasn’t a straight white male. In the process, the artists re-examine the roles of racial and sexual minorities in American society. As you stroll through the galleries, you constantly come up against the question: Male gaze versus female gaze? Black gaze versus White?

Colescott’s bold, brightly colored works range from mischievous reworkings of classical paintings to original compositions focusing on particular historical figures. In the latter, he offers centuries-spanning, densely populated canvases in which a key figure – Christopher Columbus, say, or African-American polar explorer Matthew Henson – is almost overwhelmed by historical personages who came before and after him. This is history painting as a tumultuous correction of the traditional record.

Marshall (born in 1955) and Thomas (born in 1971) pick up where he left off; they were on hand at SAM this week to comment on their work.

Marshall says his large-scale “Souvenir” paintings, combining acrylic, collage and glitter on unstretched canvas, serve as “a kind of requiem for the 1960s.” They depict winged Black visitants in cozy living rooms sometimes adorned with commemorative posters for John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. The paintings are populated on their margins by figures “popularly identified with the goals and the dreams and the hopes of the Civil Rights era,” Marshall says.

When asked if these 1960s homages tap with unexpected urgency into our own “wacky” (my word) political times, he gives a wry laugh.

“Well, no,” he says. “What you have to keep in mind is that for Black people America has always had a kind of wacky, kind of crazy history. Nothing has ever been as it was claimed to be.”

To Marshall, it all boils down to a single thing that’s “being wrestled with … in the art world, in the movie world, in the political world, in the social world. Do Black people belong here? … They are here, but they are not citizens. That’s what the whole of the Civil Rights movement was all about. And in the art world, it was like: Do Black people belong in these museums?”

Marshall’s “Vignette” series, in which an ecstatic Black couple dances in whirling embrace in garden surroundings, captures an even more central essence of African-American life.

“You can think about the history of Black people in the United States, and you can become pretty depressed about it,” he says. “But you can’t really build your life around despair.”

His aim with the series was to picture “desire that’s not circumscribed so completely by a history of victimization. … What about those spaces in-between? Let’s see what that looks like.”

So he turned to 18th-century Rococo painting, especially a series titled “The Progress of Love” by French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard, for inspiration.

“Do we experience that kind of joy too?” he asks. “And if we experience that kind of joy, can we show it?”

He shows it beautifully.

Thomas, 16 years younger than Marshall, has one work in the show that lines up neatly with its “history painting” focus. Titled “Resist,” it finds an echo of Trump-era turmoil in indelible images from the 1960s. “I didn’t think it was really necessary for me to use images of today,” she says, “because I feel like, as a viewer, we bring that forward.”

Most of her work isn’t so directly topical.

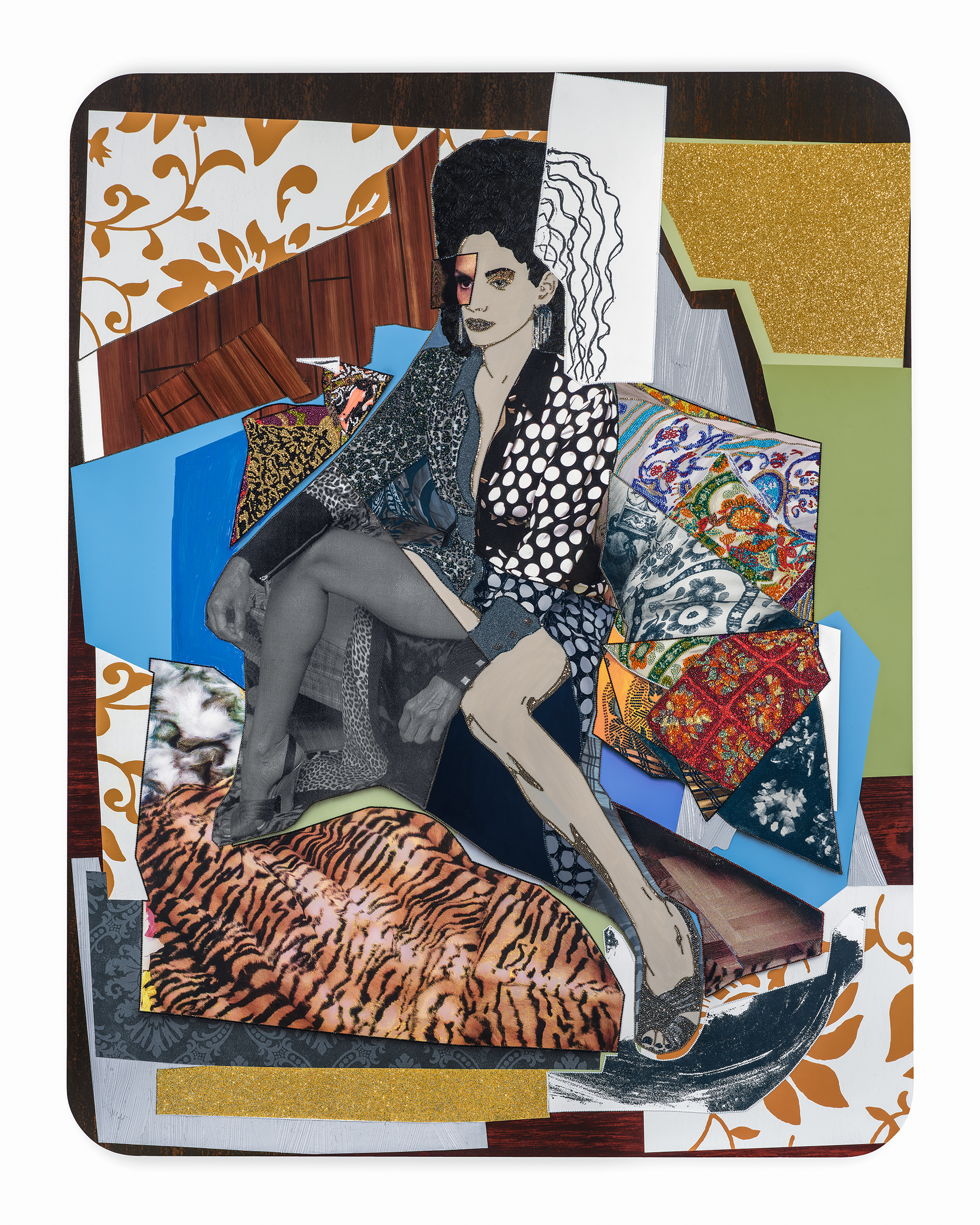

Her rhinestone-ornamented, collage-like paintings see African-American women in an alluring, empowering light. Her aim, she says, is “to allow them to exude their prowess and their energy. And hopefully, that’s what’, conveyed because it’s what I find attractive.”

Thomas is canny on how past male depictions of women influence her own lesbian sensibility.

“There’s evidence of a sort of maleness, I would say, in my work. … A lot of our experience of what we know is through the male gaze because that was so much of how we learned – through patriarchal understandings of how women see themselves. … So we’re unraveling that and relearning ourselves through our own gazes.”

Her cue, she says, comes from her sitters, including her romantic partner Racquel Chevremont.

“With the women I work with, there’s a collaboration. They have a lot of the control of how they want to be perceived – what they want to wear and which wigs. So, it’s a lot of conversation and role-play.”

With a grin she adds, “Sometimes I’m just there to experience it.”

That experience, in her hands, takes dazzling, liberating form.