When the new, $99-million Burke Museum of Natural History opens in late 2019, it will be a visual spectacle. Passersby on the sidewalk at the edge of the University of Washington campus will have a full view of a hanging skeleton of a beaked whale and an illuminated glass totem pole. The old Burke is hidden by trees. The New Burke will be a neighborhood presence.

Designed by the Seattle architectural firm Olson Kundig, the New Burke expands the museum’s exhibit space by roughly 50 percent. Storage for its permanent collections — some 16 million objects, including rocks, fossils, birds, fish, dinosaur bones, Native American and Pacific Rim cultural artifacts — will grow too, allowing for less crowding of materials and space to expand the collection for years to come, says the New Burke’s project director, Eldon Tam.

But the boldest step is the Burke’s move toward transparency on a scale perhaps unique among major museums. Along with relics, specimens and art, the museum will put the Burke’s own researchers on display. Visitors will get to see paleontologists, ethnographers and biologists, ornithologists — all the ’ologists! — doing their lab work and research in full public view. The New Burke describes it as “turning the museum inside out.”

The new museum will have glassed-in work areas for scientists, staff, students and volunteers right in the exhibit galleries displaying relevant collections. In the paleontology gallery, for example, you might be able to watch researchers preparing dinosaur bones. In the ethnology section you could see people restoring native baskets. The Burke’s behind-the-scenes tours for members have been a popular annual event. Now “behind the scenes” will be up front, visible all day.

The concept is being tested in the old Burke — still open while the new museum is under construction — in what the museum describes as a “dress rehearsal.” One current gallery exhibit called “Testing Testing 123” has been remodeled into a series of glassed-in areas where researchers are working. The Burke staff is hoping to work out wrinkles and get public feedback. The experiment is open to the public until Jan. 7, 2018.

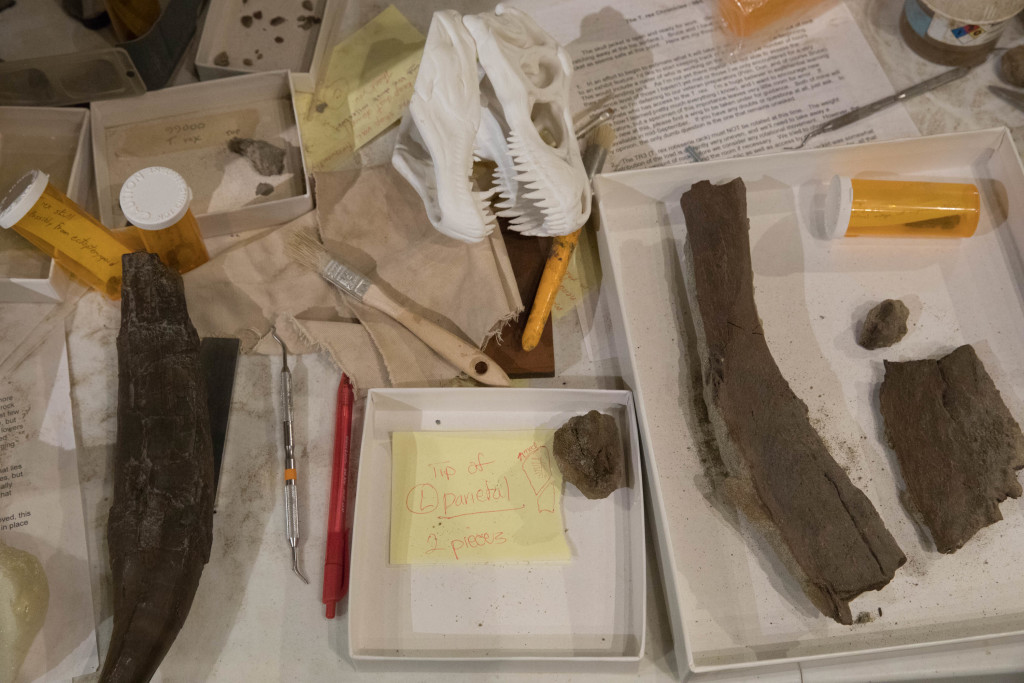

One thing they’ve learned is that visitors will often stand for a long time to watch tedious tasks. Burke paleontologists are currently working on slowly scraping a massive T-Rex skull out of rock. It was dug up in Montana and is one of only about 15 such skulls available to researchers in the world. Visitors can watch the painstaking work of a volunteer who uses a plastic substance to strengthen cracks in the bone as it emerges.

The skull sits in a massive, rotating custom-made cradle that Michael Holland, an experienced T-Rex “preparator,” designed. He calls it a “T-Rex rotisserie.” The heavy fossil, still lodged in sandstone and protective plaster, can be rotated in stages to provide access to various parts of the skull as it is chipped from the rock and treated. The plan is to have the T-Rex skull ready for public display in the New Burke when it opens.

Holland says having people staring through the glass is inspiring. He can relate to the wonder and curiosity he sees in kids peering at him, he says. “I can put myself inside those little faces.”

Some visitors leave notes and drawings on the glass, messages for the researchers inside.

In another part of the testing gallery, archaeological researchers behind glass are using special x-ray scanning equipment to determine the composition of metal components in 2,000-year old Roman glass. (While the Burke specializes in the Northwest and Pacific Rim, early gifts to its collection include items from all over the world — they even have an Egyptian mummy.) The Roman glass data is compiled for outside researchers and can help locate the origins of this ancient glassmaking. One wonders if Dale Chihuly would be interested in this line of glassmaking inquiry?

The techniques for analyzing the composition of these ancient flasks is applicable to other things, such as tracking down the origins of obsidian used by our region’s early hunters. Where did they get their raw materials for spear points and arrowheads, and how far were such things traded?

A computer screen and an adjacent exhibit shows artifacts taken from a place called Japanese Gulch in Snohomish County near Mukilteo. It was an early 20th century community centered around a logging operation that employed many Japanese workers until the 1930s. Old shoes, fragments of ceramic bowls and the like are being cataloged to offer a window on the enclave.

Burke archaeologist Peter Lape says that in the New Burke’s archaeology gallery, there will be an exhibit comparing garbage piles through the ages, from ancient middens to early Seattle dumps and beyond. Garbage pits are gold for archaeologists, as our refuse tells a great deal about our times and place.

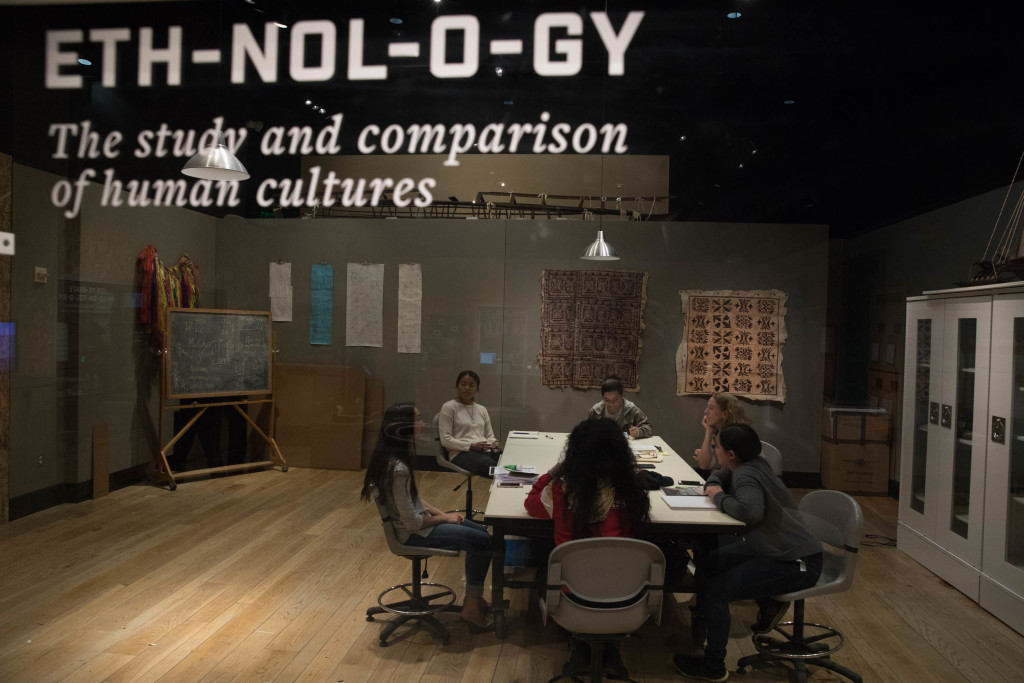

Another room houses Ethnology. On this day, a group of UW students from Pacific islands is meeting with the curator of the Oceania and Asia collection, Holly Barker. A model of a traditional outrigger sailing vessel sits on a shelf. A blackboard shows evidence of a language class in Hawaiian. On a table is what looks like a loose decorative weaving but is in fact a highly sophisticated navigational stick chart from the Marshall Islands. Sticks from palm fronds have been woven together with shells to record ocean wave patterns and swells to help islanders navigate at sea.

Another room houses Ethnology. On this day, a group of UW students from Pacific islands is meeting with the curator of the Oceania and Asia collection, Holly Barker. A model of a traditional outrigger sailing vessel sits on a shelf. A blackboard shows evidence of a language class in Hawaiian. On a table is what looks like a loose decorative weaving but is in fact a highly sophisticated navigational stick chart from the Marshall Islands. Sticks from palm fronds have been woven together with shells to record ocean wave patterns and swells to help islanders navigate at sea.

Connecting Pacific islander students with these artifacts and bringing in their families to help with cultural interpretation and to tell stories about their meaning helps solidify the students’ connection to culture and identity.

Looking at these students through the glass is a reminder that the Burke is not simply about fossils and ancient objects, but living cultures that have something to teach us. The stick chart is a reminder that “science” predated Western science — these navigational tools were the result of incredible long-term observation and knowledge about how things worked in the island ecosystem, and things like this hold historic data useful as climate change alters land and sea.

Barker says one lesson is that the peoples of Oceania have been incredibly resilient over thousands of years. They have endured droughts, typhoons and even atomic testing. Instead of seeing them as merely climate change “victims,” we should “listen to the islanders” to learn how they have been so resilient and adaptive over time, she says.

Barker says one lesson is that the peoples of Oceania have been incredibly resilient over thousands of years. They have endured droughts, typhoons and even atomic testing. Instead of seeing them as merely climate change “victims,” we should “listen to the islanders” to learn how they have been so resilient and adaptive over time, she says.

By making exhibits, research and collections visible to the public, the Burke is creating an entirely new museum environment, one in which the visitors become part of the process of investigation, says Kathryn Fernandez, the Burke’s Director of Interpretation — or, as she calls it, “Director of Transparency.”

“We’re finding that real magic has been revealed to us,” she says of “Testing Testing 123.”

Andrea Godinez, the Burke’s PR manager, says that magic is that “visitors go through and are mimicking the scientific method that researchers use every single day.”

That is the real revelation about the New Burke. Watching scientists do their work changes the museum experience from one where visitors observe to one where they ask questions. It’s interactive, and it’s highly inquisitive.

Tell us about that skull. What are you putting on it? How does your x-ray work? Why is this in your collection? How does that navigational chart work? Instead of merely looking at static objects and reading text on the wall or impersonal interactive computer screens, visitors are mobilized to inquire. It’s a personal STEM education without feeling like a dull “ology” class.

To facilitate this kind of interaction, Fernandez says, the gallery spaces in the New Burke will have trained volunteers to welcome visitors to the galleries and answer questions. Sliding glass windows can open the spaces up between workers and visitors, and sometimes visits into the work spaces will be possible.

In the New Burke, literally every day there will be something new to observe. It will be a museum in motion seeking to share not only the riches of its collection but the process of discovery itself.