Every day this summer, Jeanne Hyde scanned the waters off the west side of San Juan Island, hoping that the killer whales would show up. All night, she streamed the underwater sounds from microphones submerged along the shoreline, waiting for the whales’ distinctive trills, chirps and whistles to wake her up.

Too often, she slept through the night.

"Day after day after day, I'd wake up the next morning and I'd check the recording to make sure I didn’t miss something,” said Hyde, 71, who has watched and listened for the whales every day for 14 years.

“And I'd just put a line through the date and the time: nothing, nothing, nothing. They just weren't here.”

This summer was “the worst year on record” for sightings of endangered southern resident killer whales in the Salish Sea, according to Ken Balcomb, a biologist and founder of the Center for Whale Research, who has been monitoring the animals for more than 40 years.

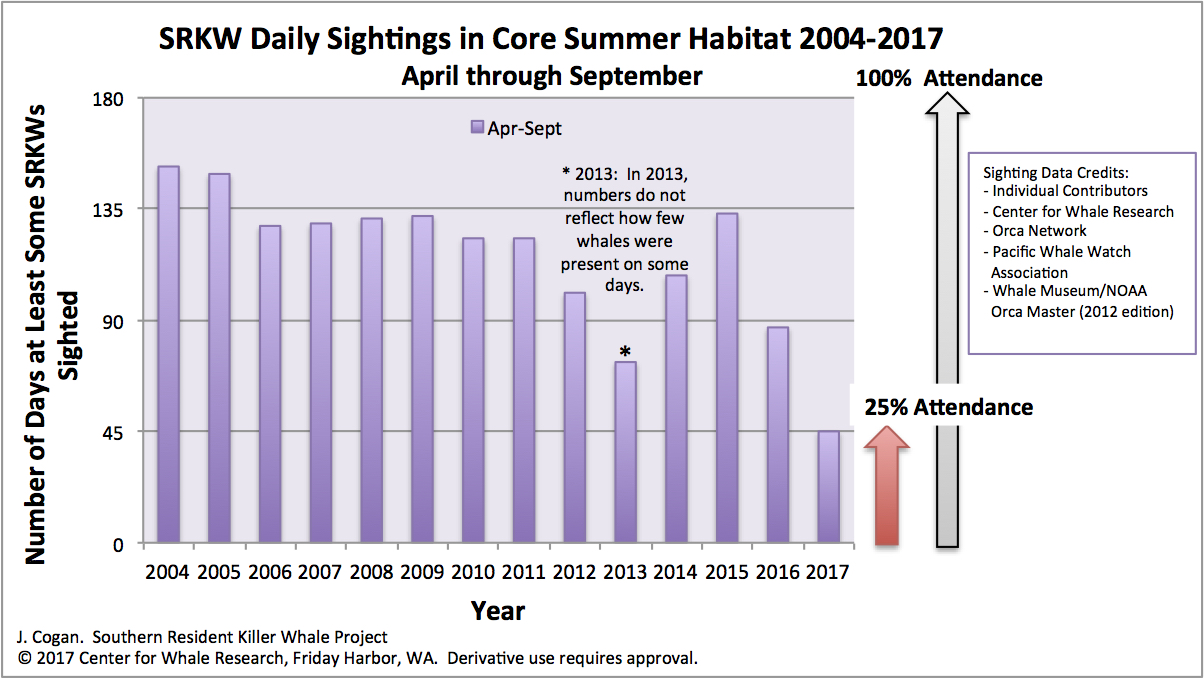

As recently as 2004, the whales were spotted 150 days from May through September, or nearly every day. This year, they showed up on only 40 days in the same period, Balcomb said. Previously, the worst year was 2013, when there were 70 days of sightings.

The southern residents, a small, distinct population of orcas, historically spent much of the late spring through early fall cruising our inland waters in pursuit of large, fatty Chinook salmon, which make up the bulk of their diet.

But with this year’s record-low Chinook runs, the whales had no reason to waste their time in the Salish Sea, Balcomb said.

The southern residents’ absence this summer is just one more signal that, without more salmon, the whales’ survival is in jeopardy. A new study, to which Balcomb contributed, concludes that the only way to increase the number of whales is to increase the number of Chinook, while also addressing other threats to their survival, including noise from ships and boats that can disrupt their feeding.

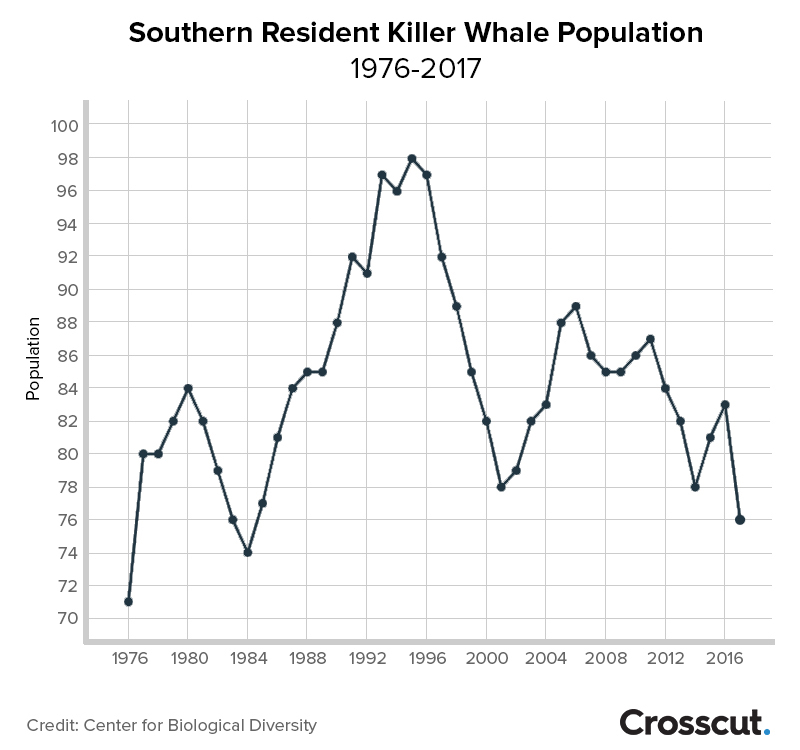

The deaths of seven whales in the past year, including a calf that appeared emaciated before disappearing in September, dropped the wild population to only 76 animals. That’s the lowest number in more than 30 years, and about half as many southern residents as probably existed before dozens were killed or captured for marine parks in the 1960s and 70s.

Orcas are having difficulty reproducing in large part because they don’t have enough to eat, with two-thirds of pregnancies ending in miscarriage, a recent University of Washington study found. No calves were born alive and survived this year.

Orcas are having difficulty reproducing in large part because they don’t have enough to eat, with two-thirds of pregnancies ending in miscarriage, a recent University of Washington study found. No calves were born alive and survived this year.

Aerial photographs over the past decade have also shown many whales with shrunken fat deposits on their heads, likely due to inadequate food. In severe cases, these skinny whales have knobby “peanut heads” and an increased chance of dying.

The southern residents are the proverbial canary in the coal mine, said Joe Gaydos, science director for the SeaDoc Society, a University of California Davis program to preserve the health of the Salish Sea.

“When you have a top predator that is suffering, it just lets you know that everything below that is also not in a good place.”

It’s not just the whales’ absence this summer that concerns scientists and observers. The three sub-groups, or pods, that make up the southern resident population also displayed unusual travel patterns.

“Not only are there now fewer sightings,” Balcomb said, “there are fewer whales in each sighting, and they are spread over dozens of square miles whereas formerly they traveled in enthusiastic and enduring groups — cohesive pods.”

This was the first year on record that the whales never turned up all together in the so-called “super-pod.” And the J pod, which tends to be around earlier and more often than the other two, was gone for all of August — another first. Some speculate that last year’s death of “Granny,” the J-pod matriarch who guided the group to the best feeding spots, also may have disrupted the animals’ historic patterns.

While the southern residents were off hunting elsewhere, Bigg’s killer whales, also called transients, were in the Salish Sea twice as often this summer as last, according to the Center for Whale Research. Unlike the fish-munching southern residents, transients prefer a diet of harbor seals, sea lions and other marine mammals, which are abundant.

The transients are “fat, they’re robust, their population is growing,” said Gaydos. Yet they live in the same noisy seas as the resident whales, and they accumulate even higher concentrations of contaminants because they are a level up on the food chain. “And so it really makes you realize that that food piece is critical,” Gaydos said.

Food is, indeed, the most critical piece, according to a new comprehensive analysis of the threats to southern residents. In order to recover the population, we’ll need to increase Chinook runs by 15 to 30 percent, the paper’s authors conclude. That’s a heavy lift, considering that decades of salmon recovery efforts have yet to yield sustained increases.

If conditions for the whales worsen, the same paper estimates a 70 percent chance the whales will be quasi-extinct in a century, meaning that only 30 individuals — too few to sustain the population — will remain. The southern resident killer whale population “has no scope to withstand additional pressures,” the researchers write.

Yet additional pressures are likely due to proposed oil and gas developments. Those include Canada’s expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline, which will increase tanker traffic, underwater noise and the risk of ships strikes and oil spills. “Our models of the additional threats expected with a proposed increase in oil shipping show that these threats will push a fragile population into steady decline,” the researchers write.

Scientists and orca advocates speak of a mounting sense of urgency, spurred by the whales’ falling numbers, skinny appearance and dwindling visits to their historic summer feeding grounds.

“We definitely do feel a sense of urgency,” said Lynne Barre, NOAA Fisheries recovery coordinator for the southern residents. “But it’s a small population and not the lowest we have ever seen them. So I still have hope that they can be resilient at their current population levels.”

NOAA is developing plans to expand the whales’ critical habitat — the area where federal agencies can’t take actions that would harm the whales, possibly including underwater munitions testing by the Navy. The protected area, which now includes almost 2,600 square miles of the Salish Sea, could expand to include the whales’ winter foraging grounds in coastal waters between Washington and central California.

Those efforts may come too late for the southern residents, many fear.

Balcomb, of the Center for Whale Research, isn’t hopeful that we can overcome the decades of “poor management and greed” that now put salmon and southern residents at a high risk for extinction.

“We should be concerned because in the big picture we are not only losing the fish and whales and birds,” Balcomb said, “we are losing the natural bounty and sustainability of the Salish Sea ecosystem.” To top it off, he added, we’re spending millions of taxpayer dollars “to accomplish this slow-motion extinction.”

Hyde, the longtime orca tracker, also wants to see less talk and more action.

The whales “can’t fix the lack of salmon; we can,” Hyde said. “We have to fix it, because we broke it.”