Sure, the Alaskan Way Viaduct is coming down — in 2019, after the new deep-bored tunnel route takes over. But don’t forget, there’s another large concrete structure now carrying state Highway 99 traffic through downtown Seattle, the Battery Street Tunnel. It’s not being dismantled.

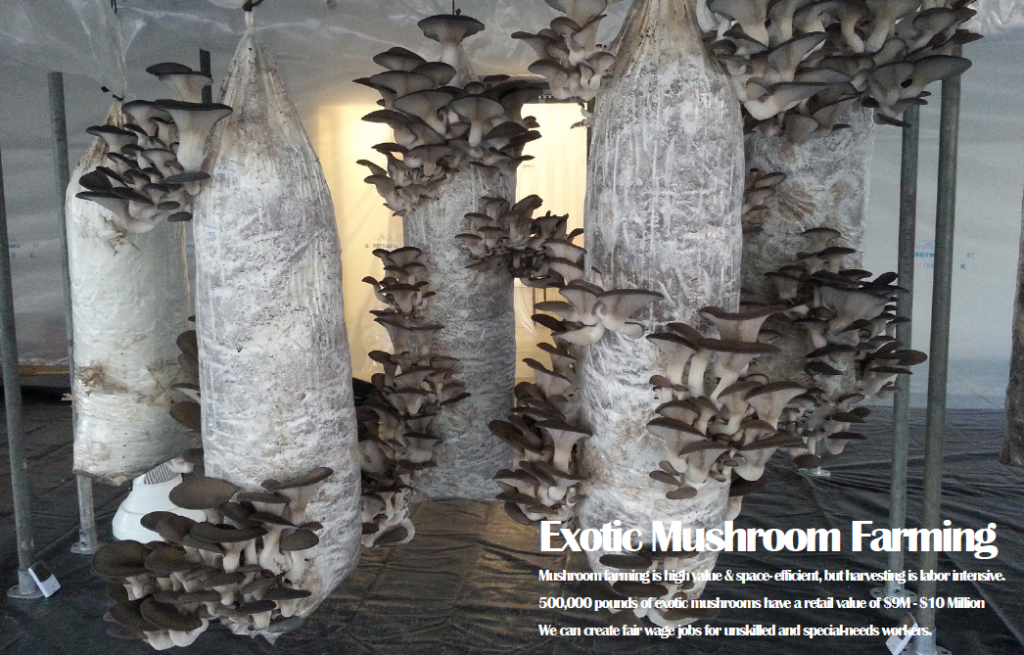

The old tunnel would make a handy disposal site for the rubble of the viaduct, says the state of Washington, which built it. Not so fast, says the neighborhood of Belltown. Residents love the 60-year-old highway structure, and want it to have a new life — whether that be as a place for mushroom farming, recycling or wastewater.

A mini design competition, titled Recharge the Battery, brought a rich collection of ideas for reusing the tunnel presented in September at a neighborhood space called Block 41 in Belltown. Sponsors included the Seattle chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA Seattle) along with the Downtown Seattle Association. Over 40 display boards showed how the underground structure could be put to work. Some of them believe it could be a great place for a park, a thrill ride, or maybe a combination of the two.

Coming up with bold ideas is the kind of thing Seattle citizens do well, and Recharge Battery is no exception. But getting them done takes political will as well as imagination.

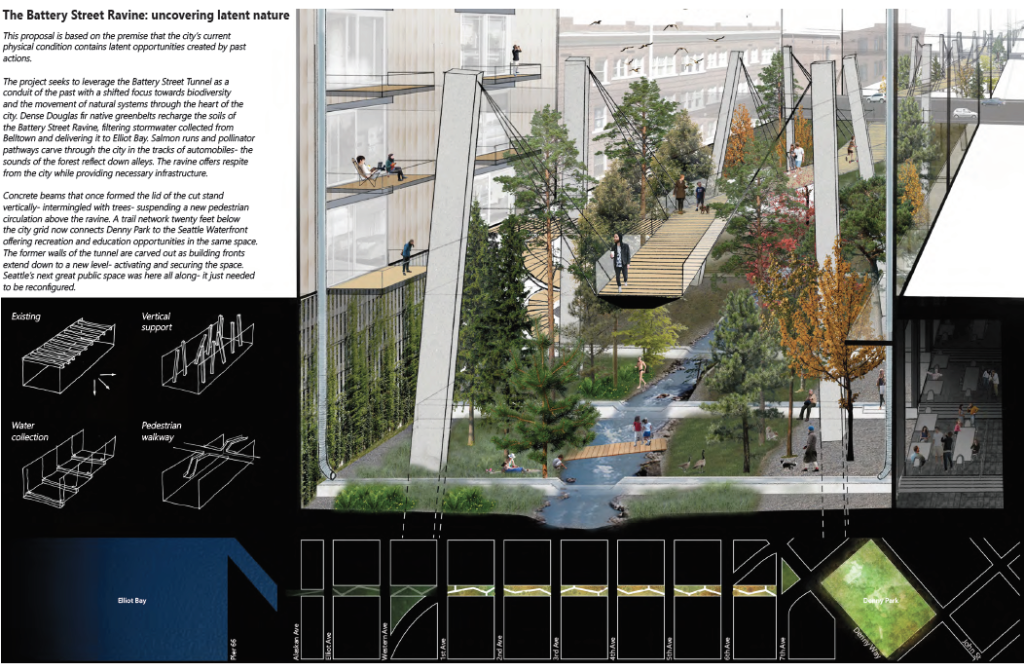

So how about sustainable wastewater infrastructure in the Battery Street Tunnel? A series of neighborhood initiatives and workshops in Belltown have shown deep interest in being an eco-neighborhood, a place where sustainable systems are tested and lived.

It’s also the kind of huge subterranean space Belltown has been wanting for decades, according to one of its prominent citizens, public artist Buster Simpson. He and his neighbors have been looking for something like this ever since they discovered that the mains beneath the neighborhood were filling up in rainstorms and dumping raw sewage into Elliott Bay, right at the foot of Vine Street. They’d like to turn that around.

It so happens that with just a couple of jogs downhill, wastewater captured and filtered in the tunnel space could be naturally polished in special planters along Vine Street. Growing Vine Street is a kind of homegrown super-green-street project dating from the 1990s and spearheaded by architects, including Carolyn Geise and Don Carlson. It’s still far from completed but it has some real accomplishments. Along with hard-working street planters, a series of functional art works by Simpson includes special downspouts, a cistern and stately steps. Simpson is credited with coining the term utilidor: utility plus street corridor.

The Battery Street Tunnel could hold almost 13 million gallons of water. Some sewer pipes go right above the tunnel, and some go below. All of this could make it a key piece of infrastructure in an evolving eco-city, and not just a tank. Think of it as a laboratory for capturing and filtering sewage. It could be a high-tech swamp or a smart detention vault, building on local experiments like blackwater treatment tanks at the Bullitt Center. Even better, it could combine this kind of thing with other industrial uses.

But wait. There are some daunting obstacles to reuse. Put simply, the state owns the tunnel structure. Even if it could be an asset to the Belltown neighborhood and the City of Seattle, it’s little more than a liability to the state. Before construction funding is found for adaptive reuse, the city faces a thicket of legal issues involving the limits of city control .

And there is little time. The question of whether the tunnel will be filled with rubble may ultimately be up to the winner of the design-build contract to demolish the viaduct. That contractor will be selected next spring, based on proposals presented in February by firms already shortlisted.

Tunnel reuse advocates are organized. Backed by Growing Vine Street, the neighborhood is hosting a slate of ongoing events around efforts to save the tunnel, including a popup storefront sponsored by Bellwether Housing, and a panel at AIA Seattle. They are launching a signature campaign to “mothball” the Battery Street Tunnel underground structure until a productive use can be identified, according to Recharge the Battery advocate Jon Kiehnau. The group is accepting donations through Seattle Parks Foundation.

The viaduct itself was once the key piece of an infeasible initiative called Park My Viaduct that would have derailed existing designs for acres of waterfront and roadway. Is interest in the Battery Street Tunnel a similar end-run, reversing key decisions already made?

No. It’s better. It deserves a chance. Underground spaces have been productively reused around the world, for industry, infrastructure and fun. The tunnel’s potential value to Seattle is clear, and should be studied.

In the meantime, there is a very practical reason for keeping the tunnel space open: city utility pipes are accessed from it.

Seattle City Councilmember Sally Bagshaw is in favor of mothballing the structure while waterfront reconstruction goes on. “I have asked SDOT and the Mayor’s Office to give the community time to consider options rather than using the Battery Street Tunnel as a dump site,” she said.

Belltown’s hunger for more open space has been well documented. But there’s more at stake. There’s pride and identity. Planned landscaping of future infill around the portals to the old tunnel should help fulfill that wish, but it’s just leftover space. The real prize is underground. With a tunnel volume about the size of the top of the Smith Tower, Belltown could have it all.

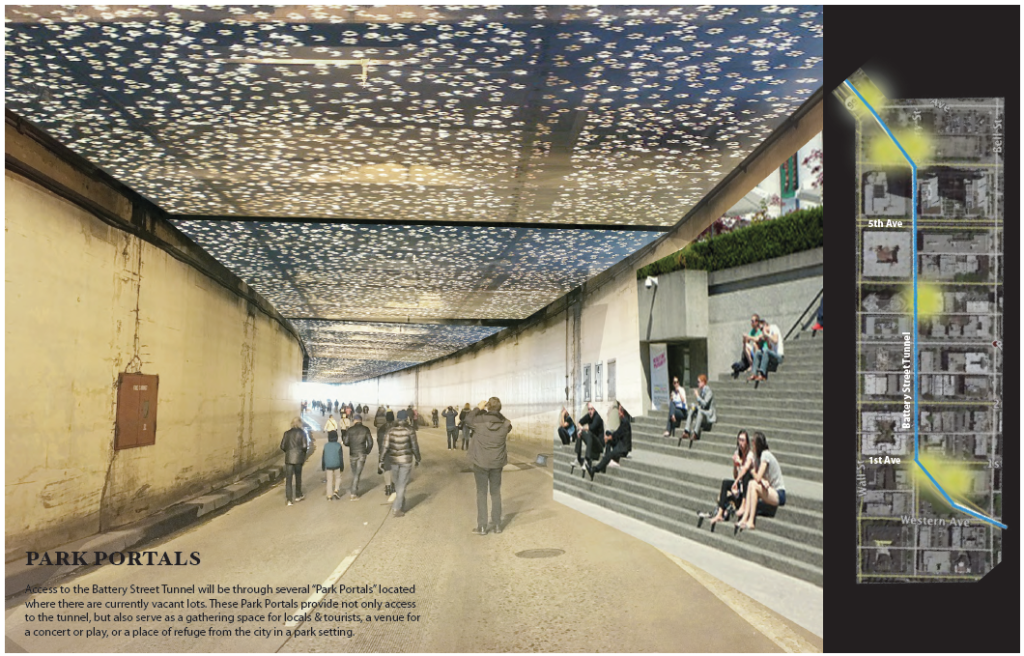

Visions from Recharge the Battery show the tunnel as a cathedral-like void where anything could happen, including a linear park. One vision has a subterranean walkway with green walls, amphitheater-like openings with steps on the side and a linear light display through the ceiling — a park without the rain. It could be a destination in winter months, when the open air waterfront is too wet.