If you travel the state and visit local historical societies, you’ll notice that “history” tends to begin with the arrival of white settlers and extend to perhaps one or two generations back. With rare exceptions, the histories of immigrants, people of color, and Native Americans are relegated to the background if not overlooked entirely. If local museums and historical societies are to reflect what is happening here in recent decades, they’ll have to vastly broaden their scope. For some, that will be essential to survival in the 21st century.

A recent event in the city of Kent underscored the challenges and opportunities of broadening who gets to write and record local history.

King County is growing rapidly and accounts for nearly half (48 percent) of all population growth in Washington. The lion’s share are people of color, including immigrants and refugees. Kent, in South King County, is a ground zero for this kind of change. It is the third largest city in the county after Bellevue, and the sixth largest in Washington. It is a former farm town, founded along the White River in the mid-19th century, and later became a Boeing suburb — the aerospace company is still the largest employer. It also has home prices far less than Seattle or the Eastside.

In 1990, Kent was nearly 90 percent white. It became a majority minority community in 2010, according to figures provided by the city. Only about a third of kids in Kent schools are Caucasian and an estimated 138 languages are spoken there, after English predominantly Spanish, Russian, Somali, Punjabi and Vietnamese.

If the immigrant story of the 19th and early 20th Century was largely told of, by and for white Europeans, the narrative now features a greater variety of voices and peoples from around the world. Outgoing Kent mayor Suzette Cooke says that the city’s 125th anniversary in 2015 made her aware that their history needed major updating to reflect the new demographic reality of the city. Of the immigrant community she says, “People didn’t realize what major history-makers they were.”

Still, these residents are not likely to find their histories in local museums, nor have they taken the time to record them for posterity. To rectify that, King County’s non-profit Ethnic Heritage Council has teamed up with partners like 4Culture — King County’s heritage arm — and the University of Washington to hold a series of workshops to reach out to ethnic, immigrant and refugee groups to provide professional advice on how to document their history and connect with local historical societies, museums and libraries to tell their vibrant stories which are new or have been overlooked.

A varied group gathered in Kent on an early October Saturday for a day-long event called “We Are History’s Keepers!” It included representatives from many ethnic communities — Liberians, Iraqis, Sudanese, Baltic peoples, Koreans, Native Americans, African Americans, Japanese and many more.

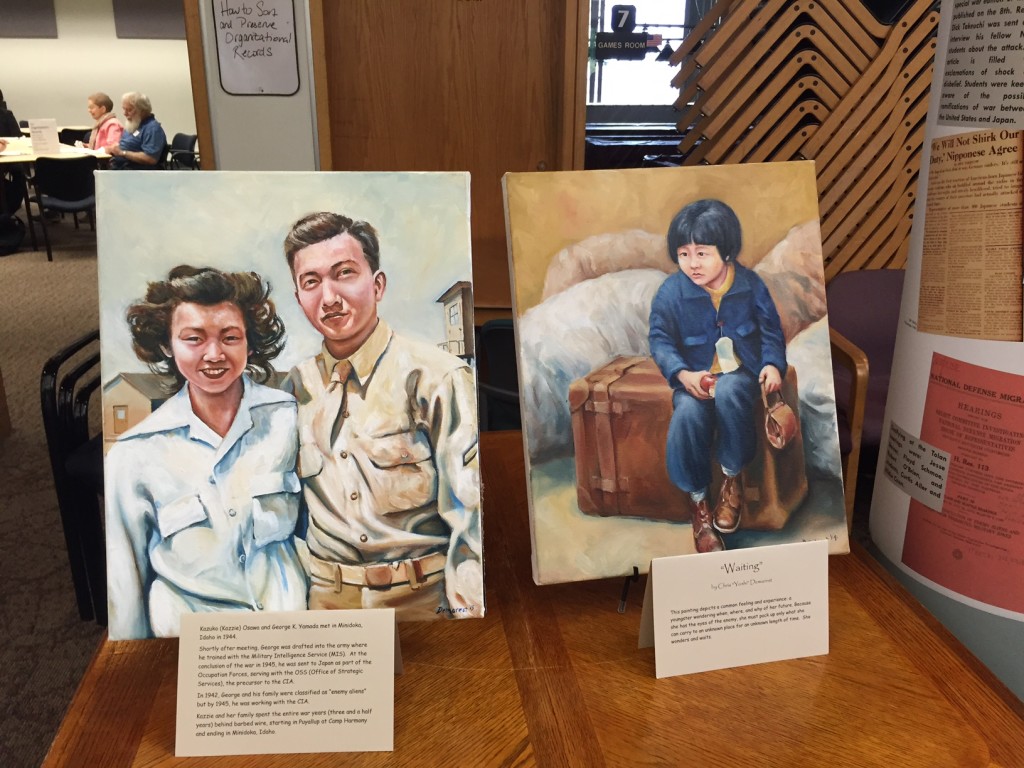

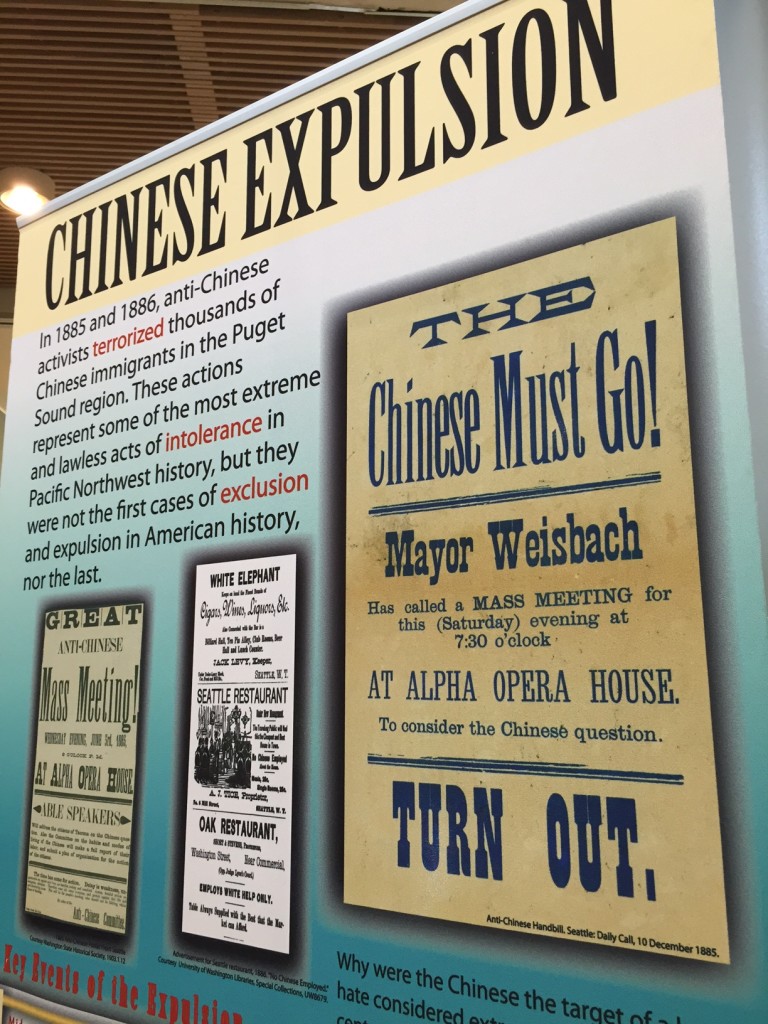

A number of heritage groups put up exhibits around the senior center where the workshops were held. There were panels describing Washington's anti-Chinese phase in the late 1800s. An exhibit by the Iraqi Community Center in Kent consisted of a cultural display. Washington has welcomed more than 3,700 Iraqi refugees since 2003.

Another exhibit reminded viewers that the Puyallup fairgrounds were once an “assembly center” for Japanese Americans during WWII with the Orwellian name of “Camp Harmony.” Another exhibit focused on the history of a local Catholic parish with strong Irish ties.

In her welcome, the Ethnic Heritage Council’s president, Rosanne Gostovich Royer, observed of the mixed audience, “One thing we all have in common: we all ended up in the Northwest.”

The Ethnic Heritage Council, founded in 1980, has recently hosted similar workshops at the Ethiopian Community Center in south Seattle and St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Hall in Montlake. This one featured UW Library and Special Collections staffers who held sessions on things like how to conduct oral histories, how to preserve photographs and digital files, and what family papers and records to keep. I attended the oral history workshop and learned about some of the projects the UW staffers are working on.

For example, the UW’s Zhijia Shen, head of the school’s East Asia Library, and grad student Juan Luo are recording oral histories of Chinese immigrants for the university’s collection. The interviewees are diverse, coming from various immigration waves and, from Communist China to post-Communist China to Hong Kong and Taiwanese immigrants.

Stories about immigrant origins and motivations can be tricky to capture, we learned. Some people have arrived in America after traumatic circumstances that they don’t want to discuss. Others are convinced that their lives just aren’t that interesting. They advised us to do research beforehand, ask people open-ended questions and set up interview schedules that capture the oldest people first.

Another UW library staffer, labor archivist Conor Casey, told us he has been documenting via oral histories the Sea-Tac $15-dollar-an-hour minimum wage campaign, one that features many immigrant workers. He has interviewed many keys advocates in the effort to get their fresh recollections. This jibes with the UW’s ongoing efforts to document the region’s labor history, but also communities of color and social activism.

Another UW library staffer, labor archivist Conor Casey, told us he has been documenting via oral histories the Sea-Tac $15-dollar-an-hour minimum wage campaign, one that features many immigrant workers. He has interviewed many keys advocates in the effort to get their fresh recollections. This jibes with the UW’s ongoing efforts to document the region’s labor history, but also communities of color and social activism.

Ethnic histories are not only about families and the immigration experience itself, but how communities are shaped and live once they are settled here. History is not just in the past, but is being made every day.

After a morning round of workshops, a delicious lunch of marinated chicken and rice and vegetables was served by the Iraqi Women’s Association of Kent. We then heard from Brian Carter, the heritage lead of 4Culture, who talked about the status of King County’s heritage groups — the majority of which focus on regional history.

They range from large, multi-million dollar organizations like the Museum of Flight to tiny historical societies with no professional staff or paid employees. Carter walked us through the results of a detailed 2016 survey of these organizations. What they found was, in general, “issues of diversity, equity and inclusion” were not considered among the topmost priorities. One reason: most are small volunteer organizations that lack visibility and public awareness, and many are on the edge financially. In other words, survival is a key problem, let alone expanding and professionalizing their collections or broadening their appeal. Money, volunteers and an ad budget are what many want most.

But the diversity piece is a potential solution for some of these groups. Many reflect a population in King County that is aging and shrinking as a percentage of the whole, they have few links to newcomers and have not cultivated ties with the immigrant, migrant and refugee residents that are reshaping their communities. Outreach and equity are not luxuries, but an imperative for many of these smaller heritage groups if they hope to survive and thrive. And 4Culture, which doles out county lodging tax money to these groups via grants, wants equity and diversification prioritized.

Another tool for the ethnic heritage community is about to come online by early 2018: EHConnect, a website that will include a detailed directory of some 1,600 state heritage organizations, a newsfeed and blog to help raise their visibility. The hope too is that ethnic group leaders will be able to network and connect.

The narrow failure (51 percent to 49 percent) of King County’s Prop 1 ballot measure in August, which would have instituted a small sales tax to support heritage, arts and science educational programs in King County, was a big disappointment, especially for diversity advocates who hoped that funding would help under-served communities and boost heritage groups.

Still, the need to revamp our heritage infrastructure to include the ethnically and racially diverse grassroots is a necessary and hopeful piece of the larger puzzle. Our history needs to reflect and reach those who are here now, not just those of long ago.