In over eight years of meetings with voters, Seattle city councilmember Mike O’Brien has never heard a nice story about Amazon.

Sitting in church basements and community centers, O’Brien has listened to the company get linked to nearly every major problem facing the city. Not once, he says, can he remember a constituent coming to Amazon’s defense. Instead, “outside of Chamber of Commerce circles,” he’s only heard a consistent stream of mixed or negative opinions about the city’s largest employer.

This fact will come as no surprise to most longtime Seattleites. The relationship between Amazon and the city has been strained for many years, long before the retailer announced a search for a second headquarters in North America — the business equivalent of saying you’re taking on a second spouse.

The tension truly began building steam in 2011, the last time Amazon shifted its headquarters. Since moving from Beacon Hill to a large swath of office space near downtown, the company has helped inspire the most crane-infested skyline in the United States, as well as the fastest growing housing prices.

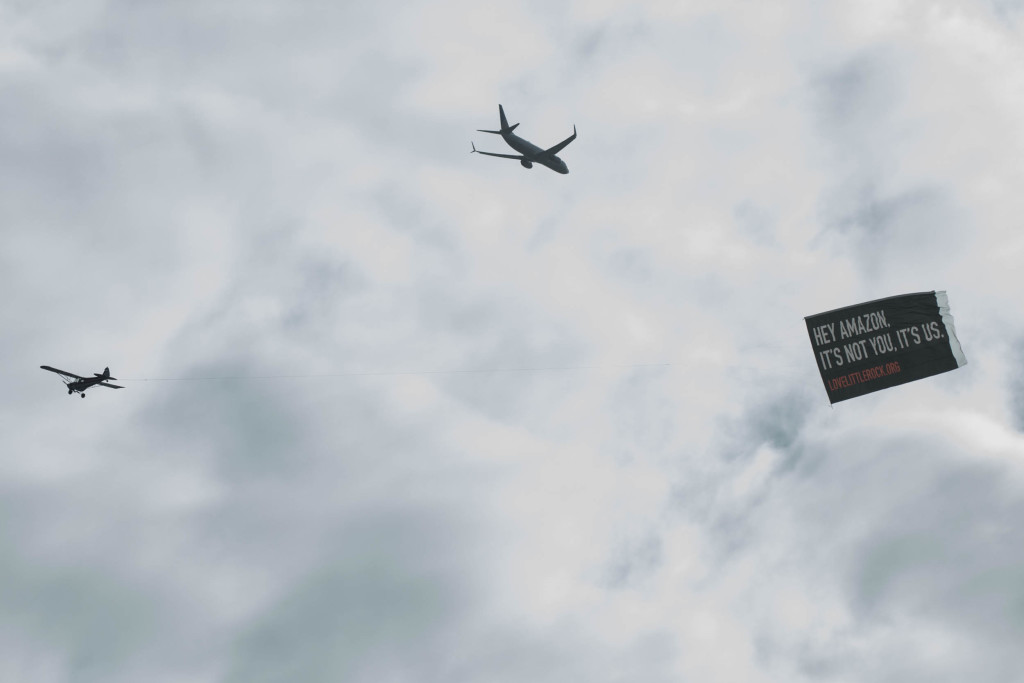

But with 238 cities, counties, and regions now vying for Amazon’s next campus, the long-simmering angst between Seattle and its golden goose has become the subject of national scrutiny, as well as local soul searching. What, exactly, makes Amazon so disliked in the city?

Is it simply a function of their rapid growth, and the pressure that’s put on local resources? Or is there something specific that Amazon does, or doesn’t do?

Amazon’s negative reputation in Seattle has roots in its philanthropy. Or its lack thereof.

To a visitor from another culture, the modern civic life of the U.S. might seem like it’s propped up by corporate philanthropy, at least at first glance. For museums, nonprofits, and even local newsrooms, corporate donors often keep the lights on. In exchange, they find their names chiseled into stone walls, and praised from event podiums:

We’d like to thank Delta Airlines, without whom this symphony would not have been possible. This exhibition of surrealist New York painters was brought to you by T-Mobile. Let’s hear another round of applause for Microsoft, who sponsored five tables at our fundraising luncheon this year.

The benefits of this charity are usually intangible for a company. At the very least, it allows them to avoid what befell Amazon.

In 2012, an investigation by the Seattle Times looked at the company’s generosity to local charities and nonprofits. The results were striking, compared to other major companies in the region. For example, the article found that Microsoft donated $4 million to the United Way of King County in 2011, Boeing donated over $3 million, and Amazon donated zero.

Overall, Amazon was painted as a tight-fisted scrooge, as well as a virtual ghost in the community, not even putting a logo on buildings or showing up to award ceremonies honoring them. It’s a reputation that’s stuck.

On their website, Amazon now lists over 70 Seattle-based charities it’s supported, including major donations to local homeless charity Mary’s Place this year, which they promoted in the media — a rare move for the company. Jeff Bezos also asked his Twitter audience recently for philanthropy suggestions.

However, unlike big corporate donors like Microsoft, Boeing, and Wal-Mart, Amazon generally refuses to disclose exactly how much it donates to charity. Unlike Microsoft and many other companies, it does not match employee donations or compensate for volunteer hours.

Among Amazon’s local critics, a phrase comes up again and again: “paying their fair share.” The general sentiment is Amazon doesn’t “give back” enough to its home city, and its lack of charitable donations play into this.

O’Brien praises Amazon for “beginning to buy more tables” at local nonprofit fundraisers, as well as their work with Mary’s Place. John Burbank, Executive Director of the Economic Opportunity Institute — a Seattle-based progressive think tank that’s been critical of Amazon — also applauds the company’s donations to Mary’s Place, as well as the University of Washington.

Amazon representatives declined to answer questions for this article on the record. John Schoettler, Amazon’s director of global real estate and facilities, recently argued to Geekwire that the company has been an active philanthropist for a while, and simply hasn’t “done a really good job of conveying our involvement.”

But if Amazon is indeed stingy toward charity, they’re fitting a trend. Since its peak of 2.1 percent in 1986, corporate philanthropy has shrunk considerably in the U.S., as measured by charitable giving as a percentage of a company’s pre-tax profits. At last count, it was down to .8 percent.

As corporations become increasingly multinational, the interests of their shareholders have taken precedence over those of their local headquarters, often now chosen for its tax benefits. Bezos has explicitly said low taxes are a major reason he chose Seattle for Amazon, after originally considering a California Indian reservation to avoid taxes even further.

Is charitable giving a fair gauge of Amazon’s local citizenship? The influential free market economist Milton Friedman once labeled corporate philanthropy as “hypocritical window dressing,” and equated it with a dishonest PR campaign. Presented with the characterization, both O’Brien and Burbank admit there’s some truth to it.

“Yes, charity can definitely be window dressing,” says Burbank. “To be honest, we shouldn’t expect corporations to put a lot of money into charitable contributions. That’s what we have taxes for. A lot of charity is to make a corporation look good while they’re skipping out on paying taxes. Amazon should be paying their fair share of taxes, so the public can enjoy more opportunity and economic security.”

Following Amazon’s HQ2 announcement, Seattle’s business community quickly used it as evidence of the city’s mistreatment and over-taxation of the company.

The HQ2 decision was “not surprising,” according to Madrona Venture Group Director Matt McIlwain, “given the strategy of our City Council to focus on taxing more those that are investing in growing and strengthening our region” instead of partnering with them. Madrona is tied to Amazon through the firm’s co-founder Tom Alberg, an early investor in the online retailer who remains on Amazon’s board.

Maud Daudon, president of the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, points out that Amazon demanded a “business-friendly” community in their request for HQ2 proposals.

“They explicitly say that they’re looking for a community where they can form a true partnership,” says Daudon. “That’s a signal that we could do a better job. There’s a perception in this community that business is seen as a problem, and is the creator of some of the challenges we’re facing. That’s a disconnect for people on the business side, because they’ve created such incredible opportunity in our city.”

Burbank likely captured the more prevalent view in Seattle, however, when he celebrated Amazon’s announcement as a chance to let the city catch its breath, rather than continue its pace of breakneck growth.

In a much-cited blog post for the Economic Opportunity Institute, Burbank labeled Amazon a “sociopathic roommate, sucking up our resources and refusing to participate in daily upkeep.” He saved particular scorn for Amazon’s expressed desire to have affordable housing and healthy transportation infrastructure near its next headquarters.

“In short,” Burbank wrote, “Amazon comes to Seattle, creates problems, doesn’t help to fix them, then starts to expand elsewhere over problems it created!”

The post cut to the heart of many anti-Amazon conversations in the city. Beyond the lack of charitable giving, tension around the company is aggravated by every day indignities.

It’s the bus route that’s become packed like a sardine can, full of passengers sporting Amazon’s now-iconic blue employee badge. It’s the off-duty police officer stopping your car for 20 minutes so a few dozen Amazon employees can leave their parking garage. It’s the rapidly rising rents, and the starter homes that now cost over half a million.

In linking Amazon to Seattle’s stretched local resources, Burbank and O’Brien argue that the company doesn’t “pay its fair share” into the local government coffers. O’Brien nonetheless admits that the company pays what it owes currently, and it’s the tax structure that deserves blame.

During O’Brien’s time on the council, Amazon hasn’t tried to extract any special tax breaks or other favors from the city, O’Brien says, unlike other locations where its satellite offices and warehouses are located.

“I appreciate the largest employer in town doesn’t throw around their weight demanding concessions,” says O’Brien. “A lot of other employers would try to do that. That’s refreshing. … When they called me after the (HQ2) announcement, they didn’t say anything about being taxed too much or a bad business atmosphere. When Boeing started looking to move their headquarters, they asked for a big tax break from the state. Amazon is not asking for that.”

Amazon does donate to a political PAC operated by the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, which tends to support more lenient taxes on business. Jeff Bezos, along with many of Washington’s wealthy, also opposed a 2010 ballot measure that would have imposed an income tax on the state’s high earners. He donated $100,000 to an opposition campaign that eventually raised over $3.5 million.

Nearly two-thirds of state voters ended up opposing the ballot measure, though, so the importance of Bezos’ donation is debatable.

Given local politicians and voters set the tax code, how is Amazon shirking its duties in paying for local resources? Burbank says that the company should simply decide to pay more, to make up for its impacts on local infrastructure. Seattle has become the biggest company town in the U.S., and Amazon should play the benefactor more actively.

Asked to give an example of a company that’s done this, Burbank cited Boeing in the 1980s, when it worked with the city of Everett, Washington — where it has a large plant — to develop affordable housing.

“We need to have corporations that, when they have rapid expansion, proactively work with city officials and agree to contribute through taxes to pay for public transit and housing,” says Burbank.

But Amazon built its business on ultra-thin profit margins. It’s a penny pincher, and in some years it runs at a loss. Regardless of how beneficial it would be, how could Amazon explain to shareholders that they’re essentially overpaying their taxes by millions?

“Well, look, we shouldn’t ever expect them to do something like this voluntarily,” says Burbank. “We need laws to ensure they contribute their fair share to the common wealth and infrastructure. Right now, we don’t have those.”

There’s reason to believe Amazon needs taxes to be a requirement. Asked whether the company should collect sales taxes in areas where it wasn’t required, in order to support local government, Bezos said in 2011 that it was up to politicians to pass laws.

“I don’t think our customers would say, ‘Why don’t you guys just optionally collect the tax? I know you aren’t required to do it, but aah, go ahead!’”

Amazon has never publicly acknowledged their home city’s disdain. One imagines it may be a factor for the retailer — the seething contempt of locals could present a challenge for Amazon’s talent recruiters — but the tension has never truly been brought into the open.

That changed this month. On October 13, in the sort of gesture that couples’ therapy is built upon, the majority of the Seattle City Council — as well as representatives from state legislature and the local education system — sent the company a letter, essentially asking for a fresh start.

“To the extent that (the HQ2) decision was based on Amazon feeling unwelcome in Seattle … we would like to hit the refresh button,” the letter reads. All the “mixed messages from our community” did not “leave a good taste in anyone’s mouth.”

The letter asks the company to “stay with us and grow with us”, and to “form a true partnership, and realign how we live and work with you in our community.” As a peace offering, it invites Amazon to join a few public-private task forces, to help shape policy around transportation, worker rights, education, public safety, and housing.

O’Brien, who did not sign the letter, describes it as “groveling at the feet of the second wealthiest person in the world.” City councilmember Rob Johnson, one of the letter’s five signatories on the council, considers it long overdue.

At the school his children attend, Johnson says, a number of parents are Amazon employees. Sometimes, they can’t help but vent about treatment by locals.

”When they talk to people about what they do, it’s not always a welcome response,” he says. “That’s not the city I came from or want to represent. … For me, it’s a reset for a discussion of what a welcoming city should look like.”

The way Johnson sees it, Seattle has a lot of issues to address as it develops into a major city. They’re not necessarily Amazon’s fault, but the company’s growth has shrunk the timeline to fix them. Elected officials should work with the city’s largest employer to plan a smarter, mutually beneficial path forward.

At the close of their letter to Amazon, local leaders express that they’re looking forward to hearing from Amazon. But Johnson didn’t rule out that silence would be the only answer.

O’Brien and Burbank also believe a response is unlikely, let alone participation on local task forces. Amazon is focused on “only one thing,” Burbank says, “and that’s building their business.” O’Brien echoes the sentiment.

“I don’t know what the culture is like over there at Amazon, but I’m guessing they see this in a pretty straightforward way,” O’Brien says. “They probably look at all this and say, ‘OK, great. But you’re a city government, so just do what city governments are supposed do. We’re a business. We’re going to keep doing our own thing.”

Seattle has a long history as an outlier, a city with its own style and values that expects outsiders — known locally as “transplants”— to adopt them. Amazon has flipped that script, filling the town with newcomers who are fundamentally reshaping the city’s character, while seemingly doing little to engage, let alone adapt to local norms or expectations.

For cities now competing to co-host Amazon’s main operations, this formerly laid-back, blue-collar town seems to offer a bright vision, but also a cautionary tale, a lesson to learn from. The subject of that lesson is the question: how much is it about the rapidly growing company, and how much is about Seattle’s reaction to it?