Mary Matsuda Gruenewald beams at the crowd in her emerald cap and gown. At the age of 92, amongst the Vashon High School graduating class of 2017, she is finally receiving her high school diploma for the class of 1943.

Graduating with her high school class is something that Gruenewald wished she had been able to do, but her high school years were interrupted.

“I was a junior when the war came and we had to leave. So I never did go to Vashon High School as a senior,” she said. “But you accept what was and say, well, ‘I had some good years here.’”

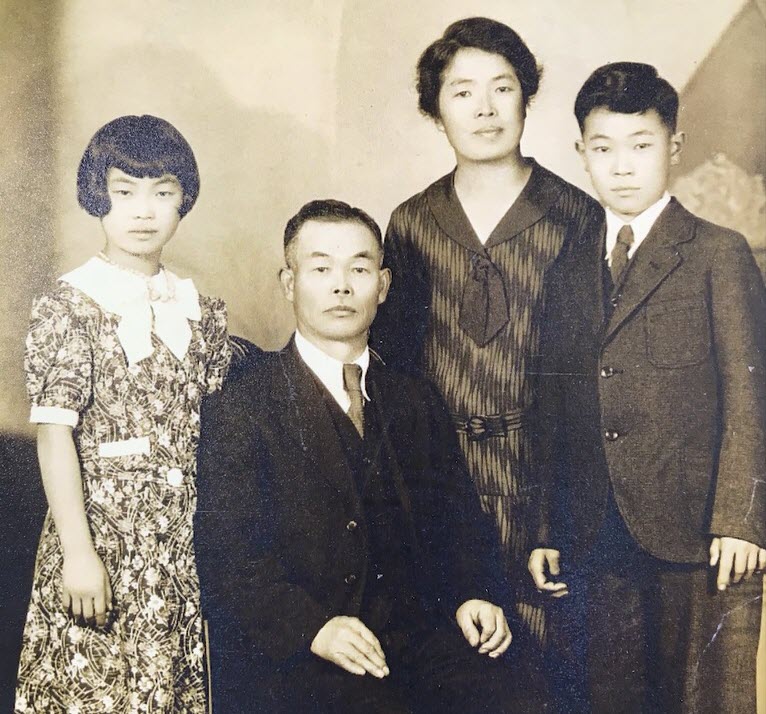

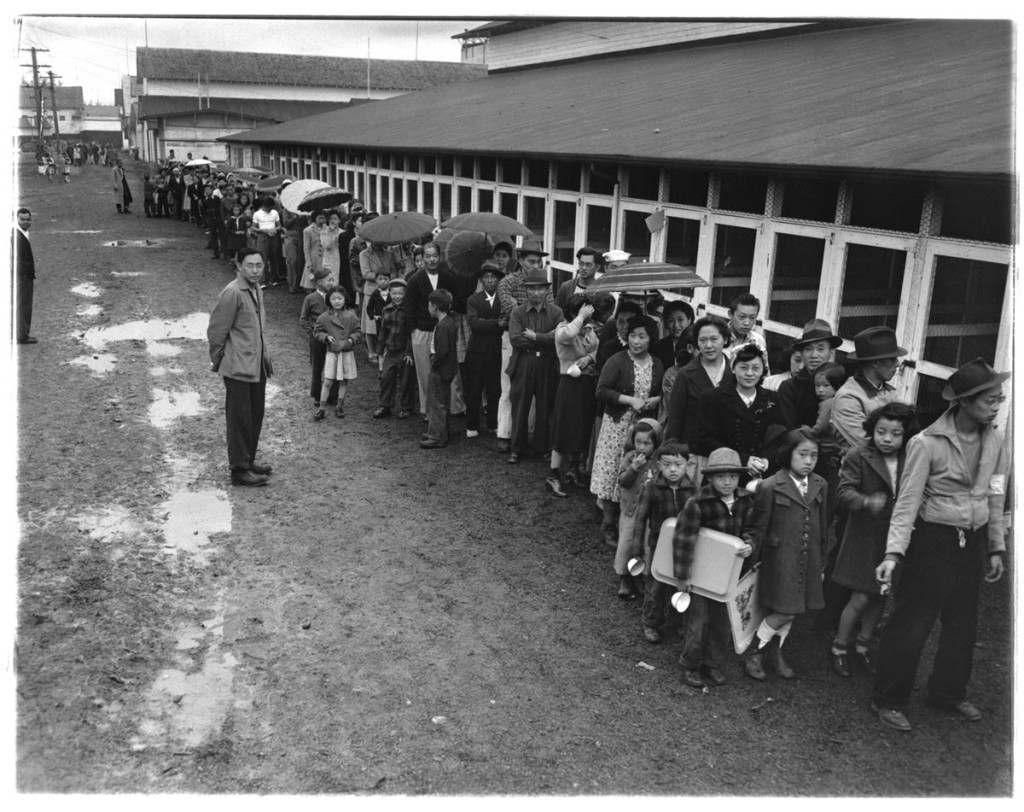

Gruenewald was walking home from Sunday school when she learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor. A few months later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the incarceration of more than 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry. Gruenewald and her family would spend the next two years at the Tule Lake camp.

Among the life moments that Gruenewald missed out on because of the imprisonment: graduating with her class at Vashon High.

On May 16, 1942, Gruenewald recalls being forced to march with other Japanese Americans away from their homes.

“We had to walk about a mile toward town,” she said.. “There were white soldiers in uniform holding rifles with bayonets attached… there were white folks who had come to say goodbye, and some of my classmates.”

When the ferry arrived, they lowered the gang plank and Gruenewald and her family boarded along with about 120 others.

They were sent to Tule Lake concentration camp in Northern California.

Gruenewald and thousands of school-aged, Japanese-American children continued their education within the confines of the camps. Students crowded into barracks-turned-schoolhouses with student-to-teacher ratios of 48-to-1 for elementary schools and 35-to-1 for secondary schools. They were taught by non-Japanese teachers as well as Japanese-American teachers who were imprisoned in the camps. Gruenewald recalls chemistry labs with no bunsen burners and a typing class where students typed on imaginary keys on paper. The days were long and tedious and Gruenewald became bored and depressed. She credits her mother’s wisdom and strength with helping her get through those years. Her mother, or Mama San, found ways to make the most of the time.

“One day Mama-San said, ‘I noticed there are some tiny shells on the ground, let’s go see if we can gather some and make something pretty out of them,’”Gruenewald said. “I noticed in her the capacity to look at any situation, no matter how difficult, and to create meaning in it ... It demonstrates that in desperation we can create beauty.”

In 1943 Gruenewald remembers a questionnaire that was given internees. It was called the “Application for Leave Clearance” but it became known among internees as “The Loyalty Oath.” Two questions in particular gave Gruenewald pause:

Question 27: Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

Question 28: Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attacks by foreign and domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or disobedience to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?

Knowing the answers would impact the fate of their family, Gruenewald looked to her parents for advice. She remembers her mother saying, “Twenty years from now, what kind of memories do we want to have of how we faced this difficulty now?”

Gruenewald and her brother Yonechi Matsuda answered “Yes” to both loyalty questions. Her brother enlisted in the U.S. Army and became part of the highly decorated 442nd battalion comprised entirely of Japanese Americans. Gruenewald joined the Cadet Nurse Corp and earned a nursing degree at the war’s end.

About 17 percent of internees responded, “No” to both questions, saying they couldn’t be loyal to a country that would unjustly incarcerate its citizens. A division rose up between the two factions, known as the “Yes-Yes” people and the “No-No” people, which lasted for decades after the war had ended.

For Gruenewald, joining the Cadet Nurse Corp set her on the path of becoming a nurse, which she continued throughout her career. She is credited with founding the consulting nurse service at Seattle’s Group Health Cooperative which became a model for hospitals nationwide.

After the war, Gruenewald’s family returned to their Vashon farm which in their absence had been in the care of a farmhand who worked for their family before the war. In the early 2000s the Matsuda family donated their farmland to the Vashon Land Trust, to be returned to forest. Since 2004, the Matsuda family and friends have planted over 2,400 native trees and plants on the land.

Gruenewald has penned two memoirs: Looking Like the Enemy, chronicling her family’s plight and resilience during World War II, and Becoming Mama-San: 80 Years of Wisdom, reflecting on her personal journey and the wisdom passed on to her from her mother.

“I wanted my children to hear what happened and others to know ... not only what happened, but why it happened,” Gruenewald said. “The consequences of the war and internment, the way it impacted different people, is incredibly complex.”

On June 17, the Vashon High School principal presented Gruenewald with a yearbook and a diploma for the Vashon High School Class of 1943. It was symbolic, but the gesture led her to tears.

Gruenewald said she wished her parents and her brother had been there to witness the occasion. She credits her family’s love and solidarity for carrying them through the dark times of internment.

“A person has to feel loved in order to heal. No matter what the pain and the hurt may be,” she said.“Each person is precious, special, irreplaceable. And we need to treat each other as though the other person is special.”